Defences in the professional game are becoming ever ‘harder’. Scarcely a season goes by without more power being added to front-line defence – spot blitzes, double teams, choke tackles, strips in the tackle, vicious ‘chops’ with pilferers waiting to pick up the pieces. The pressure on the ball-carrier is growing every year.

In the URC, that hardness on D has been added, and multiplied by the arrival of South Africa’s four primary, ex-Super Rugby franchises (the Sharks, Stormers, Bulls and Lions) in the competition. The final of the tournament in 2022 was fought out between the Stormers and the Bulls, with the Cape province emerging victorious.

All of the South African teams deploy their own versions of the Springboks’ rush defence, with huge pressure on the breakdown and an ‘umbrella’ preventing easy access to the wide channels. That defensive intensity reflects the importance of the game in the country.

As the Leinster Director of Rugby Leo Cullen pointed out,

“When you are in South Africa, it is the number one game in terms of where rugby sits as a team sport when you compare it to soccer, Gaelic football and hurling, whereas it’s one, two, three and four down there. They live and breathe it.

“You can see some of the size profile, the speed profile, the skill, jacklers over the ball, some of the front-rowers that they have, it is a proper challenge.”"

In response, attacking methods to get the ball quickly to the edge need constant refinement for the attacking side to be able to exploit the full width of the field. One of the easiest methods to reach the wide channels has been the ‘kick-pass’, with ball travelling from the boot of the first receiver (typically the number 10) straight to the wing and cutting out the rush defenders in the intermediate space.

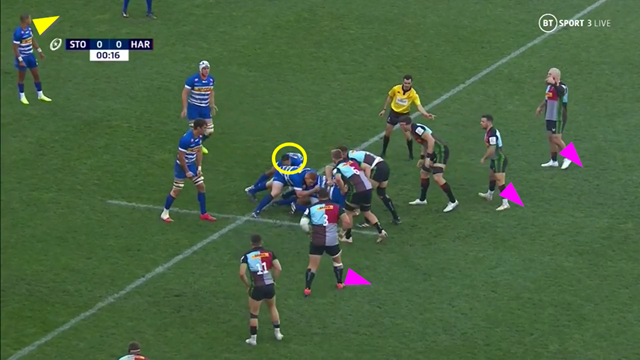

The defence has not been slow to find solutions. In the following example from the recent Heineken Champions Cup round-of-16 game between the Stormers and Harlequins, the kick-pass from the boot of Quins’ Marcus Smith was effectively neutralized by Stormers’ full-back Damian Willemse:

Although Willemse starts well inside the left 15m line, on the far post when the kick is launched, he can use the time the ball spends in the air to make up ground and disrupt the catch by wing Joe Marchant. The eventual result is a knock-on, and a turnover scrum to the Stormers.

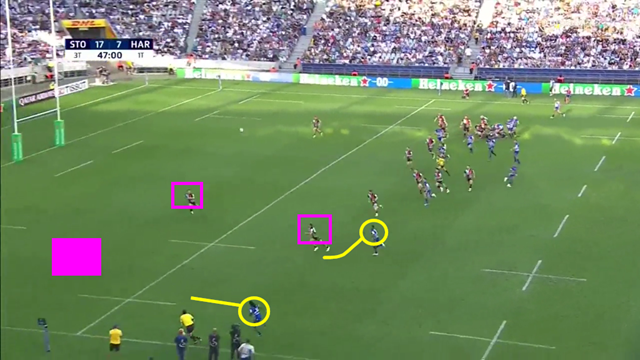

Coincidentally, it was the Cape-based outfit who streamlined a method to make the kick-pass work during the same match, and they announced their intent right from the opening kick-off:

There is a great deal of finesse in the set-up for the play. All of the blue-and-white forwards (in a ‘caterpillar’ ruck) and the number 9 Herschel Jantjies are showing the tells for a box-kick exit. Most the Quins’ defenders are already rocking back on their heels anticipating it, and only the Stormers number 10 Manie Libbok is reading another option, looking out wide left.

The key improvement in Libbok’s version of the kick-pass is the flat trajectory and the single bounce before it arrives in the hands of Stormers’ left wing Seabelo Senatla. The ball gets to the target area quicker and there is less time for the defence to react. Libbok imparts back-spin to the kick to ensure the ball kicks up off the ground, rather than kicking on into touch. Two phases later, the men from the Cape were in for a length-of-the-field try.

There were four such kicks in the match, with three successes for a healthy 75% success rate:

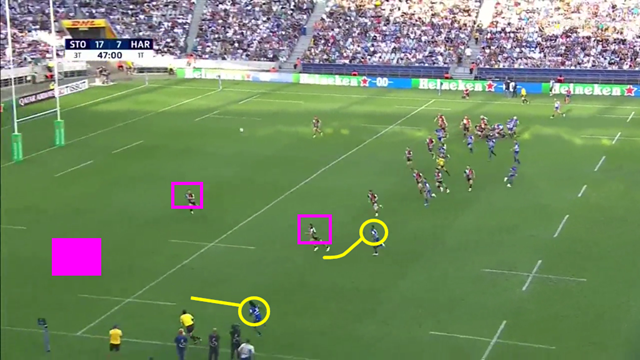

This instance occurred from a second half scrum, and it was the third occasion on which the Stormers had tried the same tactic, so Harlequins must have been expecting it on first phase. There is still nothing that the last two defenders can do about it. Senatla still reaches the ball first and it still kicks up obligingly into his hands, with Willemse on the all-important first inside support line.

The fourth and final example occurred towards the end of the third quarter, on this occasion from a left-side scrum with the kick going right from Libbok out to wing Suleiman Hartzenberg:

Once again, the trajectory is flat enough to minimize reaction time for the defence, and the back-spin imparted stops the ball when it hits the turf rather than encouraging it to kick on into touch. It may be a ‘hard ground’ tactic but it is one that would work on the majority of high-quality grass (or synthetic) pitches being produced in the professional era.

Summary

The Stormers-Harlequins knockout game in the Heineken Champions Cup showed how the dynamic between attack and defence is in a continual state of flux, and ‘conversation’ through the medium of the kick-pass. Quins used the older iteration of the kick-pass, intended to reach the wing on the full, and it was defended successfully. The Stormers unveiled their streamlined version, flatter and kicking back on the first bounce, and it worked for breaks or tries on three of four occasions. The tactical dialogue of the game is still alive and well!

.jpg)

.jpg)

_no_button.jpg)