The great American track-and-field athlete Jesse Owens once set four world records in a Collegiate meet at Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1935. The novelty was that he did it all within the same clock hour, in what has been called ‘the greatest 45 minutes ever in Sports’. They came, one after another, in different disciplines – the 100-yard dash followed by the Long Jump, 220-yard sprint and finally the Low Hurdles.

Owens was only 21 years old, and one year later he was repeating the feat by winning four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics – albeit over the less spectacular time-frame of seven days.

At Michigan’s Ferry Field on 25 May 1935, all of his results were achieved with a bad back. After winning the 100-yard dash at 3:15 p.m., he was breaking the Long Jump record only ten minutes later, going on to win the 220 at 3:34 before crushing the opposition by a full five yards in the hurdles.

By four o’clock in the afternoon, Owens was done. He had to leave by climbing through a bath-room room window to avoid the huge crowd which had gathered to pay homage to his achievements. But a plaque still stands outside Ferry Field to this day, commemorating that remarkable 45 minutes of repeat effort.

Owens himself flagged up that need to make effort beyond the ordinary range when he said,

“In the end, it’s extra effort which separates a winner from second place. But winning takes a lot more than that too. It starts with a complete command of the fundamentals. Then it takes desire, determination, discipline and self-sacrifice. And finally, it takes a great deal of love, fairness and respect for your fellow man. Put all these together, and even if you don’t win, how can you lose?”

Sports coaches are always on the lookout for ways in which a player can make a double action or second effort, reinforcing and improving the first, creating a snowball of momentum.

One of the sweet spots where this can be accomplished on a rugby field is at the breakdown. With professional teams averaging anywhere between 150-250 rucks per game at a 95%+ retention rate, new methods are being found to disrupt the smooth supply of attacking ball at the breakdown.

The value of second efforts at the ruck is rising all the time, particularly on defence, and especially when all seems already lost. That effort can be individual, but more often than not, it is collective in nature. In the recent Heineken Champions Cup semi-final between Leinster and Toulouse, both sides stretched the envelope of the contest and pressurized the attacking ruck from the very beginning to the very end.

The individual meaning of a second effort was exemplified by 6 foot 8, 140 kilo Toulousain second row Emmanuel Meafou:

Leinster have picked up a loose ball and are moving forward with it, and Meafou loses the initial battle of the shoulders with the two cleanout players opposite him. But a failed pilfering attempt is not the end of the effort. The young giant still has the ability to make an extra force on the play, driving the man sitting above the ball (Charlie Ngatai) back into scrum-half Jamison Gibson-Park to create a knock forward.

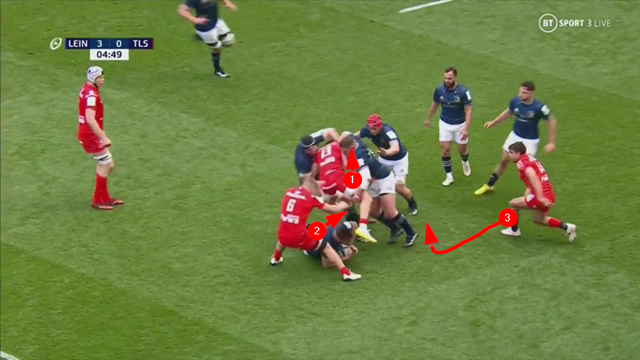

There is frequently a small ‘loophole’ of relaxation when the attacking side believes it has won the ball at a ruck, and that is the time to launch counter-attacks. Here is an example of a collective Toulouse effort after a Leinster kick-off receipt:

Under ordinary circumstances, the ball would appear to be won when two Leinster players clean out Toulouse number 13 Pierre-Louis Barassi. But as soon as that cleanout expires, a second player is waiting (number 6 Jack Willis), then a third, reloading from his initial chase ahead of the ball (#14 Juan Cruz Mallia). It is like peeling away the layers of an onion, and eventually even Leinster’s scrum-half has to become involved in the ruck battle, which means there will be no box-kick exit possible.

Leinster also played their own longer version of the same theme. In this instance covering two consecutive rucks, number 7 Josh van der Flier (in the red hat) is making the same choice to renew the attack right up the middle of a lost ruck:

In the first instance, the Leinster jackal is peeled away successfully from the ball – but instead of dropping back passively into defensive ‘Guard’ for the next play, Van der Flier attacks the acting scrum-half (Willis) straight up the middle.

Just to make sure that nobody views it as an accident, he repeats the action on the very next play, forcing a knock-on:

Once again, the initial pilfer attempt fails, but that is not the end of the play. Van der Flier is ready to peel the onion and expose another layer at the base of the ruck. He moves straight through on to replacement scrum-half Paul Graou instead of dropping back into line, and that is the end of the attacking sequence.

Summary

Rugby athletes would be very lucky indeed to find themselves in a situation where they could ever hope to emulate Jesse Owens’ achievements at Ferry Field, but the man himself pointed out the need for that extra push which extracts the very best out of every scenario. It is particularly true at the ruck, where repeat efforts on defence pay dividends against a ‘relaxed’ cleanout. It can be individual or collective, but if you make the second effort “even if you don’t win, how can you lose?”

.jpg)

.jpg)

_no_button.jpg)