How to use decision-making in contact to help your attack

When he first burst upon the international scene, Steven Luatua was something of a sensation. Big, athletic, great in the air and with ball-handling and offloading skills to burn. The world was at his feet.

At the age of 29 years old, and now plying his trade in Bristol in the UK rather than Auckland in New Zealand, there has been a definite change. With his days in the All Blacks now probably behind him, Luatua has continued to refine himself steadily in areas of the game which are not so obvious to the onlooker.

While the ball skills are still valued in Bristol head coach Pat Lam’s expansive attacking approach at the Bears, Steven Luatua has undergone a metamorphosis. He has become one of the most outstanding technicians in contact work at the ruck in the English Premiership.

That work is vital, even if it goes largely unobserved. One of the chief aspects is ball placement – presentations to the half-back which oil the wheels of the attack on next phase and generate momentum rather than subtracting from it.

Falling with your body in the correct position to protect the ball from a steal, buying time with a second move on the ground, and deciding whether to present right, left or dead centre to enable the cleanout and clearance by the number 9 from the base, are all significant factors.

Here are some examples from a recent Gallagher Premiership match between Bristol and London Irish.

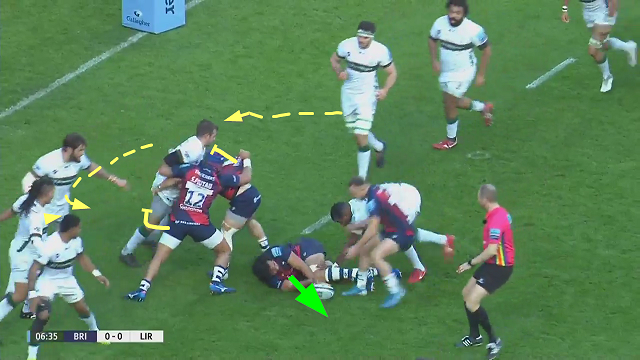

The first instance is also the simplest. Steven Luatua picks up the ball from the base of a breakdown in the opposition 22 with nothing obvious ‘on’. His aims in this situation are twofold, but connected: 1) to run at the outside shoulder of a defender close to the ruck and make the ‘wrap’ to the far side by the defence more difficult to achieve; and 2) to enable an easy cleanout for his support, one which produces quick (sub 3 second) delivery for the next phase:

Luatua cleverly runs behind the shield provided by a retreating London Irish forward (number 2 Saia Fainga’a) and succeeds in engaging the first Irish back (number 10 Stephen Myler) to achieve the first objective.

He then delays the moment of release to allow his cleanout support maximum impetus as they drive across the ball:

The two Bristol cleanout players have driven well beyond the tackle and that means the Irish forwards have to run a longer way around to fill the defensive positions on the far side of the ruck.

Luatua has wrapped his left leg over his right to cocoon the ball from a steal, and he has presented it in the direction of the next phase of attack towards the Bristol left.

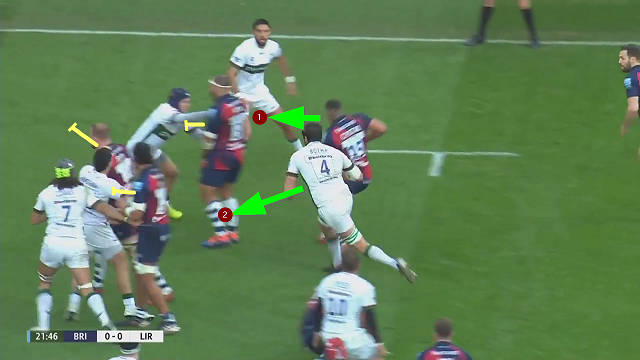

The second example is rather more complex. At first, Luatua shows good body awareness to avoid what looks to be a developing choke tackle, sinking his weight quickly to the deck when he feels he is in danger of being held up. That achieves the aim of winning an easy ruck ball:

But then, a question arises: why has Luatua chosen to fall on his left shoulder, and present the ball on the right side of his body, when his scrum-half appears to be running off in the opposite direction?

The answer to this question is revealed by the subsequent progress of the play. The Bears’ half-back is a decoy, dragging elements of the Irish defence across field in order to open lanes for full-back Charles Piutau, cutting back to the short-side:

At the critical moment, Piutau has two promising channels to exploit, and both are naturally shielded by the presence of the three Bristol forwards who were originally cleaning out over Luatua at the ruck. Piutau picks channel “1” and releases wing Luke Morahan down the right on a short break.

Steven Luatua has in fact placed the ball in the correct direction for the way in which the play was set up. His presentation enables Piutau to cut back to the blind-side and allows the constructive use of the three forwards present at the cleanout to create running lanes thereafter.

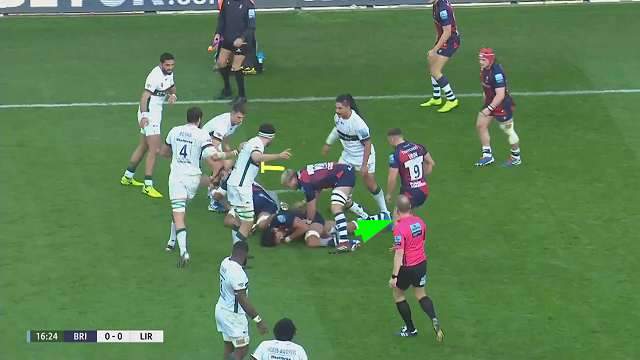

The final example shows how ball placement can be used to facilitate a kicking exit:

There is more than one point of interest on this play. At first, Luatua is a little isolated, with two defenders in on the tackle and his support temporarily away from the ball. Luatua makes a ‘save’ by releasing the ball, then picking it up again. That double move effectively buys him an extra second and an extra metre to prevent any contest for the ball on the deck. By then, the support has closed up and is in place.

The second point of interest lies in the actual ball placement itself. Instead of presenting on the right or left side of his body, Luatua places it between his legs (as if laying an egg) in what is known as a ‘squeeze-ball’ position. Why? Because he knows that the Bristol number 9 is preparing to kick straight upfield on the next phase, so squeeze-ball provides maximum ball security, with the whole of Luatua’s upper body in between the opposition and the ball:

To adapt a well-known maxim from American Football: the flashy offloads may win you a game or two, but it’s the accuracy in contact which wins you championships.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_no_button.jpg)