Is the breakdown really a ruck anymore?

World Rugby is still wrestling with the issue of what happens, and what should by law happen after a tackle takes place. The two only occasionally overlap in the modern professional game.

The governing body issued new guidelines aimed at cleaning up the post-tackle back in July 2020, after an extensive review by its own specialist breakdown working group. One particular focus was a reduction in head and neck injuries for the ‘jackal’ – the defender who tries to pick the ball up immediately after the tackle has been completed.

Many concussive head contacts occur when a cleanout player is looking to remove the jackal. This example comes from the 2021 Six Nations game between Scotland and Wales:

The first Scottish cleanout player is struggling to remove the jackal via a pulling action with his arms, so a second fires in to remove him more directly with the shoulder. Unfortunately, there is contact to the head, and that means a red card under the current protocols.

Incidents like this spotlight the difficulty of removing a jackalling player without making contact to the head or neck area. In the strictest terms, jackalling is also against the law, which states that “Players involved in all stages of the ruck must have their heads and shoulders no lower than their hips.” (Ruck 15.3)

By definition, any attempt to pick up the ball on the ground and turn over possession after a tackle has been completed involves dropping the shoulders below the height of the hips.

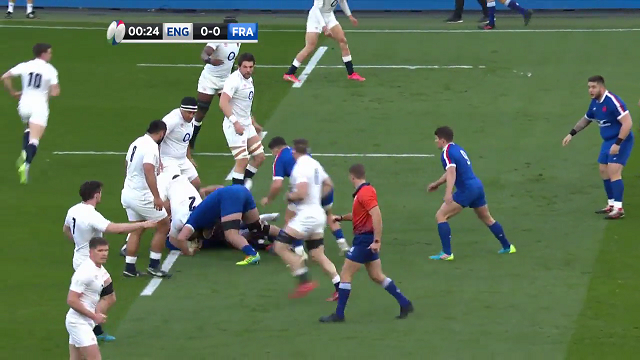

Let’s look at the most basic building blocks of the situation as it now. The following examples are taken from the recent Six Nations match between England and France:

This is a one-v-one cleanout between Kyle Sinckler (England) and Gael Fickou (France). With the jackal (Fickou) bent double over the ball, the cleanout player is taught to win ‘the battle of shoulders’ and adopt a lower position than the defender in order to achieve leverage:

.png)

Sinckler does what he is supposed to do, scissoring Fickou’s arms and driving him away from the ball. But the process starts with the shoulders of both players well below hip height, and it ends with Sinckler leaving his feet and effectively sealing the ball off from further contest.

“Arriving players must not go off their feet to kill the contest by ‘sealing’ ”, stated the revised 2020 guidelines.

This issue is not an outlier, it is a fundamental problem created by the protection of the jackal as a species:

With a starting base as low as this – no more than two or three inches away from the grass – it is very hard to see how the cleanout player can stay on his feet if the defender pulls out, or takes a step back; or how arriving players from both sides can effectively bind on to the situation to build a meaningful ruck.

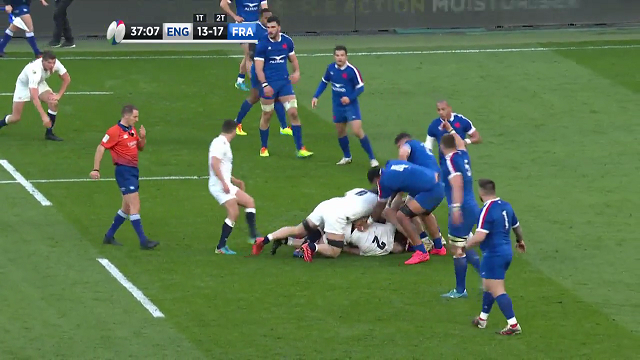

The scenarios involving more players from both sides also involved very low contacts, and attacking players leaving their feet in order to make the cleanout:

The key to further improvements, and building a more comprehensible structure at the ruck, may lie in the reinforcement of Tackle Law 14.5.d:

“Tacklers must allow the tackled player to release or play the ball”.

If the defender is required to allow the ball-carrier to release or play the ball before attempting to pick it up, it will already be an arm’s length away from this dangerously low, shoulder-to-shoulder/neck/head contact, and there will be more chance of arriving players staying on their feet.

From this view point, there were two more interesting examples from the England-France match – both coincidentally, involving the same English player, number 7 Tom Curry. First, on defence near the England goal-line:

Here the assist tackler (Curry) is never required to release the tackled player, nor does he allow him to play the ball. It is a typical ‘flashpoint’ scenario where arriving cleanout players have little choice but to engage the head/neck/shoulder area of the jackal, but nonetheless it was England who were awarded the penalty.

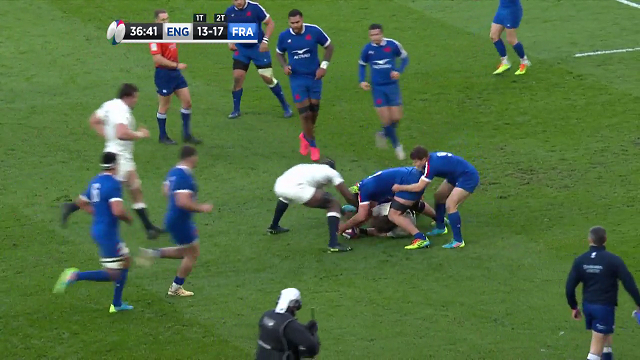

Now let’s look at a situation where the defender probably should have been rewarded with a turnover penalty:

Curry makes a good long placement of the ball, but the defender (France number 8 Gregory Alldritt) is clearly the first to arrive, and is supporting his own bodyweight:

Despite the long presentation, Curry does not release the ball for more than two seconds on the ground, and Alldritt is unable to pick it up: “Tackled players must immediately make the ball available so that play can continue by releasing, passing or pushing the ball in any direction except forward.” (Tackle 14.7.a). The penalty was awarded to the attacker, not the defender.

The key to further improvements in the post-tackle is immediate release: by both the defender(s), fully releasing the ball-carrier and allowing them to make a move to place the ball away from the body; by the tackled player, placing the ball immediately, without any extra movements on the ground and without keeping their hands on it to prevent turnover.

In the next companion article, I will take a look at ways in which this development may encourage a revival of the counter-ruck (rather than the jackal) as the weapon of choice on defence.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_no_button.jpg)