Why are the ‘new’ rules are creating problems at cleanout in Super Rugby Aotearoa

First, a qualification to the title of the article. There are no new rules at the breakdown, however there have been some significant changes of emphasis, and some tightening up of refereeing interpretations, which have changed the complexion of the tackle area in the reborn version of Super Rugby Aotearoa.

With these new interpretations due to be exported to the other major rugby playing nations from early July onwards, it is important that as many wrinkles as possible are ironed out before they are trialled in South Africa, Argentina and the Northern Hemisphere.

A useful summary of the refereeing priorities at the contact area can be found in this video, explained by ex-international official Bryce Lawrence.

Over the next couple of articles, I will examine how the new rules are affecting play in New Zealand. The first will focus on impacts to the attack, the second will take a look at effects on the defensive side.

The raw stats give a general feel for changes on both sides of the ball. In week 2 of SRA, there was an average of 26.5 penalties awarded over the two games (including pens which were subsequently played through to an advantage) – much higher than the usual Super Rugby expectation.

66% of the total penalties awarded were for offences at the breakdown, with a slight preference for the attacking side – 37.7% pens to the attack compared with 28.3% to the defence.

Average ball retention rates fell away sharply because of the upswing in breakdown penalties. Where the attacking side could reasonably expect to lose around one ball in 20 rucks under the ‘old’ rules in 2019, they can now count on an interruption by the whistle at one in every 7 rucks.

The coaching response has been unequivocal. When a coach cannot be sure he/she will be able to keep the ball in contact, there is a major loss of incentive in constructing multi-phase attacks. Coaches have turned to the kicking game with a vengeance, with an average of 66 kicks per game over the two matches at the weekend!

Let’s take a look at how this issue is playing out in practice. According to Bryce Lawrence’s video, the major priorities for players in cleanout support are as follows:

“Arriving players must come through ‘the gate’ – their side of the ball with their backside facing between their corner flags. They must not go off their feet to kill the contest by ‘sealing’. Tackling the jackler’s (ball poacher’s) legs will be deemed dangerous play.”

Coupled with the speed of release now being demanded by both ball-carrier and tackler, it is a tall order to satisfy all of these requirements within the time frame allowed. It is fair to say that all of the teams have struggled with the accuracy required thus far.

Here are some of the situations which are most likely to provoke coaching concern. They will require more refereeing flexibility in the remainder of the SRA tournament before they are exported elsewhere:

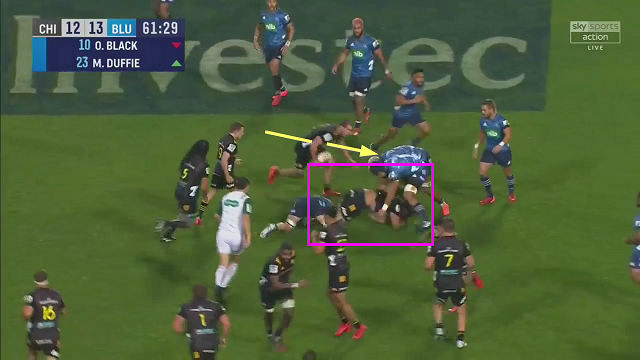

The first couple of instances (from the Chiefs-Blues game) illustrate the need for attacking supports to stay on their feet throughout the ruck:

The first is an example of tackling the defender’s legs and knocking him down as soon as he presents a threat to the ball. This is now deemed to be dangerous play, even though it looks no different to an ordinary tackle, but without the ball.

In the second illustration, the ball-carrier clearly wins the collision and falls forward in the tackle. The first arriving player (Blues number 2 James Parsons) creams the tackler off the top so that quick ball can be presented to his scrum-half. He leaves his feet to do it, but it is not material to the outcome of the play, and his intent is positive.

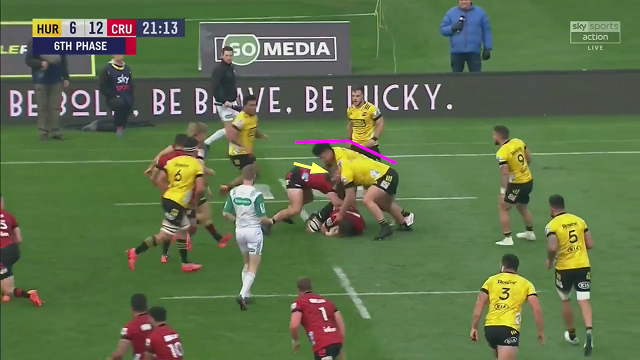

The following examples illustrate two applications of the new ‘sealing off’ rule from the Crusaders-Hurricanes game:

In the first example, the Crusaders’ number 2 Cody Taylor falls over the feet of his opposite number as he enters the tackle zone, but reloads immediately. Even though there are no Hurricanes defenders threatening the ball, he is penalized for sealing off the contest.

The scenario represented by the second instance will probably become a major bone of contention as the new rules develop. The first supporting player (Crusaders’ wing George Bridge) enters the tackle zone as low as possible in order to protect the ball. Cleanout players are always taught to win the battle of body height in order to win this particular contest:

Bridge wins his height battle against two Hurricanes’ forwards but is penalized for sealing off – even though he has extended his arms out in front of him to support his own bodyweight.

The other primary emphasis for support players is the need to come through ‘the gate’. In these two examples from the Chiefs-Blues game, the first arriving player is pinged for a side entry on both occasions:

Cleanout supports are typically taught to remove a defender’s base – his ability to stand up in contact – but taking away a player’s legs often implies an angle into the ‘tackle’.

There is no question that the Chiefs’ cleanout is coming from outside ‘the gate’…

…but with a demand for immediate release on both sides at the tackle, where can the cleanout support find the time to go the long way around and adjust their angle into contact?

Over 26 penalties and 66 kicks per game is clearly not what the new rulings at the breakdown were aiming for. It is now up to the law-makers and the referees to provide sufficient incentive for the attacking side to keep the ball and construct multi-phase attacks as Super Rugby Aotearoa unfolds, and find the right point of balance.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_no_button.jpg)