Why Rugby is creeping into the grey area at ruck and maul

Professional coaches spend an awful lot of time looking for loopholes, or grey areas within the rugby lawbook which they feel they can exploit. These are in modern times quite extensive, and there is plenty of scope for interpretation (by referees) and experimentation (by coaches and players)!

Nowhere is that mix of interpretation and experimentation more intensive than at ruck and maul. Italy famously achieved a huge, yet lawful ‘cheat’ at the ruck in their 2017 Six Nations game against England by pulling defenders out of the ruck as it formed, or ensuring they were not bound on to any other player on the ground.

Under the laws as they stood at the time, it meant that a ruck had not formed and therefore there was no offside line for the defence to respect. The Azzurri were able to creep up on to England’s side of the ball throughout the match and stymie all their attempts at attack with ball in hand. The law was changed soon afterwards to prevent a repeat scenario!

A few months later, I wrote an article on The Rugby Site illustrating another lawful ‘cheat’ in maul defence, based on a European Champions Cup match between Benetton Treviso and Leinster.

Throughout the game Treviso had a defender on the edge of a maul use his bind to swing around on to the ball-carrier at the back of the drive, or the scrum-half trying to clear the ball, and block clearance. Look at the actions of the Treviso number 7 in this instance from the original article:

As I pointed out at the time, this represents a ‘smart-assault’ on Laws 16.4 and 16.5 governing offside at the maul:

“16.4. Each team has an offside line that runs parallel to the goal line through the maul participants’ hindmost foot that is nearest to that team’s goal line. If that foot is on or behind the goal line, the offside line for that team is the goal line.

“16.5. A player must either join a maul from an onside position or retire behind their offside line immediately.”

Because the defender joins from an onside position and never releases his initial bind, his actions are legal – but they hardly look fair and natural, and there is no high-value application of skill involved.

Since then, this method has become a major plank in defence of the lineout drive at the elite level of the professional game. Witness these examples from recent end-of-year tour game between Scotland and Australia:

The Scotland fringe defender (loose-head prop Pierre Schoeman) starts with a left-arm bind on his immediate opponent, then uses it to creep around on to the Australian side – to the point where his sitting right next to the ball-carrier, and the ball has to be moved away.

Some of the examples looked every bit as ridiculous as the events at the ruck in the England-Italy game:

The big Wallaby second row Will Skelton has an opponent directly in front of him, but he also has another (in the red hat) attached firmly to his coat-tails as the maul struggles to advance!

Now, it appears that virus has spread to rucks where a box kick exit off number 9 can be expected. In the recent Gallagher Premiership game between Saracens and Sale, the home side had clearly developed a new idea to test the limits of the offside law and the refereeing of ‘creepage’.

A typical set-up for the box kick exit would look like this:

The kicking team builds a ‘caterpillar’ of blockers to give the kicker protection, while the first edge defender (Saracens number 4 Maro Itoje) strives to rush from an onside position behind the hindmost foot to block the kick down.

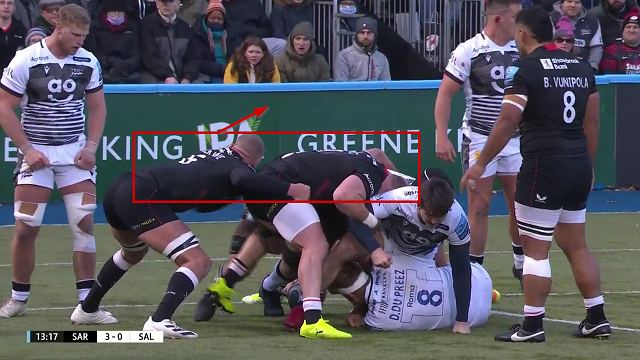

On three occasions during the game, Saracens experimented with a more liberal interpretation of the bind in order to get the blocker closer to the halfback:

It is a rough translation of the same defensive technique utilized at the maul. The potential blocker (Nick Isiekwe) uses his bind on the defender at the back of the ruck to swing around on to the kick. While all the Sale players are pointing North-South directly upfield, the two Saracens forwards are looking East-West and shaping towards the far side-line.

Here is the same method viewed from another angle towards the end of the game:

Itoje attaches himself to the back man and then tries to use the bind to swing himself around into the path of the kick.

The offside laws governing ruck and maul would clearly benefit from another thorough overhaul by World Rugby. The question of how a defensive bind affects the notion of offside is very much alive and well, despite the adjustment made after the England v. Italy match back in 2017. The bind can be used by a smart defensive side to position themselves far closer to the ball at both ruck and maul than should be possible – at least if the spirit, rather than just the letter of the law is to be the criterion of judgement.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_no_button.jpg)