Why the English Premiership is ahead of the game

It is not often that you can say, with confidence, that the UK is leading the world in rugby innovation. Historically it has hardly ever happened, except maybe for a brief period around 1971-1973, when the legendary Carwyn James coached the triumphant British & Irish Lions tour of New Zealand.

It is happening again now – not with developments in coaching, but in refereeing. When World Rugby announced a raft of new law revisions in and around the tackle area in June 2020, they were designed to clean up the breakdown: producing quicker ball for the attacking side, and giving the defender a shorter window to ‘lift’ and pilfer the ball on the ground.

The new principles are explained very well in this video by New Zealand Rugby Referee Manager Bryce Lawrence and current official Paul Williams:

There are three main changes of behaviour indicated:

1. Preventing any extra movements on the ground by the ball-carrier before release – “Ball-carriers are allowed one dynamic movement on the ground before they place/pass. If they are clearly held, they cannot crawl forward after hitting the ground.”

2. Getting the tackler away from the ball quickly. “Tacklers must not impede the attacker’s ability to clean out – they take all responsibility to get out. To reward a jackal (defender trying to pick up the ball on the ground), the tackler must not impede the cleanout. Dealing with the tackler is the Number One priority.”

3. ‘Jackals’ are required to support their bodyweight throughout the process in order to win the ball. “To be rewarded, a jackal must arrive first, in a position where they are supporting their own weight, and show a clear lift of the ball with both hands. ‘Bouncing’ past the ball, and then [dragging the hands] back on to the ball is NOT allowed.”

Over the past few months, these guidelines have been applied far more stringently in the English Premiership than anywhere else. The next two articles will illustrate how the Premiership is rewarding behaviour that clears the tackle zone quickly, while the recent Trans-Tasman competition tends to reward the turnover, and protect the ‘jackal’ who produces it.

In England, the current buzz-word is ‘LQB’, the short-hand for ‘Lightning Quick Ball’ – that is, attacking ball which comes from a one or two second ruck delivery. Premiership refereeing is creating an environment where this ball can be generated consistently.

Let’s look at some examples from two recent Premiership matches between Harlequins and Bath (77 points and 10 tries), and Wasps and Leicester (69 points with nine tries), which produced a total of 19 tries and 146 points between them.

The primary directive for English Premiership referees is to clear the tackler away from the tackle zone quickly and decisively. Tom Foley (the official for the Quins match) set the tone by awarding six penalties for the tackler failing to roll away in the first half alone. He did not reward jackals who failed to support their bodyweight throughout the process:

The Quins number 7 is over-extended at the start of the process even though he gets his feet back underneath him subsequently, and the result is a penalty. The change of behaviour is immediate. The Bath number 9 scoots away from the mark, and one offload later, a try is scored underneath the posts.

The game was chock-full of instances where tacklers clearing the tackle zone quickly were key to producing LQB on the following phase of play:

In both instances, the tackler’s first action is to flip from the attacking to the defending side of the ruck as it forms. The outcome is the desired one-to-two second ball – and in the larger picture, forwards who want to run, handle and attack space on the next phase.

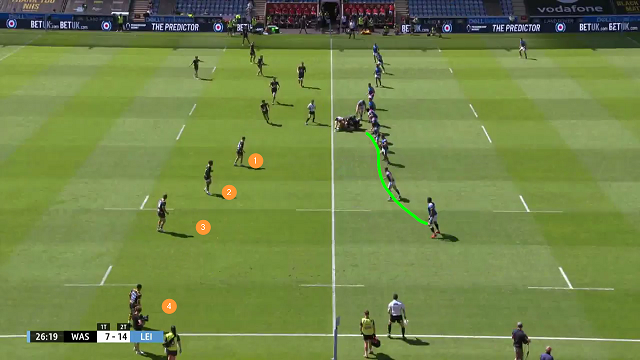

Now let’s take a look at a longer try-scoring sequence from the Wasps-Leicester game, in which attacking opportunity is created by three swift rucks in succession:

At both of the first two rucks, the tackler rolls yards and yards away to provide clear access to the ball for the attacking cleanout and number 9. On third phase, he rolls out ‘East to West’ as the new guidelines originally required.

The outcome is a definite attacking opportunity for Wasps, with a succession of high tempo rucks delaying the defensive rush and giving access to the full width of the field:

The macro result has been to produce an explosion of scoring very unfamiliar to English rugby supporters. The last round of games in the English Premiership for example, averaged over 60 points per match.

In the recent Trans-Tasman tournament, the refereeing emphasis has been entirely different, with the rights of the defender attempting to steal the ball protected above all else. The partner article will address that alternative interpretation of the ‘new rules at the breakdown’.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_no_button.jpg)