It was back in early 2014, and I was working as the main analyst for Stuart Lancaster’s England. The challenge later that year (in July) was a forbidding one, a three-Test series in New Zealand. The All Blacks had won the World Cup in 2011 and only one year later, they would become the first-ever nation to win the William Webb Ellis trophy twice, back-to-back. It is fair to say that England were going to take on a team near the peak of its powers.

During the six-month preparatory process, I stripped every aspect of New Zealand’s game back to its component parts in order to appreciate it better. At the time, I was using a grid system to deepen understanding of team efficiency at the ruck. I broke the field up into a grid of a dozen different zones (six in each half of the field) and calculated how well an attacking side could retain the ball, or a defensive team turn the ball over in each of the 12 areas.

One of the most interesting results of the exploration was the discovery that on defence, New Zealand generated over 90% of their turnovers in the wide zones, from the 15 metre lines outward. The All Blacks’ D was designed to bend, but not break in the middle of the field (between the two 15’s) but as soon as play moved beyond the 15m line they ‘switched on’ and actively hunted a turnover of possession.

Those wide areas of the grid still remain to this day, a ‘sweet spot’ where the defence can move over to the attack at the breakdown. A basic example of the ‘Why?’ behind the stats occurred in the recent Super Rugby Pacific match between the Queensland Reds and the Brumbies:

Attacking play moves from midfield across the left 15m line, and into the hands of the Brumbies’ left wing Corey Toole. Initially there is only one man in support (open-side flanker Rory Scott, in the white hat) and he is consumed in the tackle. That leaves the Brumbies scrum-half Nic White to handle duties as the second cleanout support, and he finds himself in a contest against a man (Jordie Petaia) six inches taller and 20 kilos heavier. It is an unequal contest and White is driven out of the play completely.

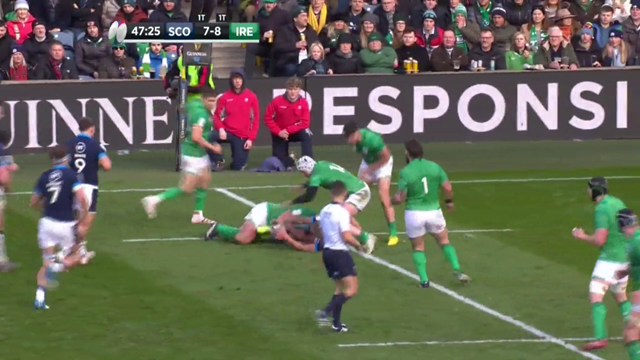

A more complete story was told in the second half of the Six Nations game between Scotland and Ireland. Throughout the Championship, the Scotland offence has been heavily weighted towards attacks down the left, mainly because of the presence of their big South African-born left wing Duhan Van der Merwe. Whenever Scotland shifted ball into the left 15m corridor, the men in green answered by looking to get their combative wingman Mack Hansen on-ball at the tackle:

It is quite a similar picture to the Reds-Brumbies clip. The two support players closest to the ball are the Scotland number 7 Jamie Ritchie and number 9 Ben White, but there is clear separation between them and the ball-carrier presenting the ball on the ground, full-back Stuart Hogg. That grants the opportunity for Hansen to intervene and win turnover before the cleanout arrives.

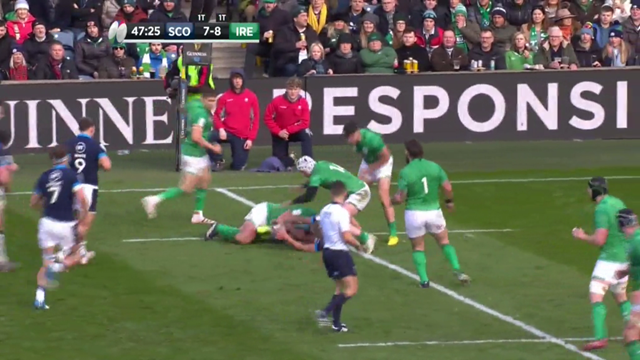

The formula was repeated again a few minutes later:

The ball is moved from midfield into the left 15m channel towards Van der Merwe, but Hansen is again first to the tackle ball, ahead of the cleanout support provided by Scotland number 12 Sione Tuipulotu.

The story does not end there. When wide ruck turnovers become such a strong feature of the game as a whole, it often persuades the offensive play-maker to change the natural shape of the attack, and against Ireland that shift did not work out well:

As soon as Hansen comes up to threaten the ball on the outside, the Scotland playmaker-in-chief, number 10 Finn Russell, turns away from potential trouble with the inside pass. What had been a strongpoint for the Saltires all season long – their ball movement out to an outstandingly powerful left wing – has been stifled and becomes a weakness instead, with Ireland running the ball back the length of the field and almost finishing a superb counter-attack of their own. Lock James Ryan fumbled the ball forward at the last gasp, in the action of making the scoring pass to James Lowe.

Summary

The All Blacks had it right all those years ago. They sucked it up in the middle, and as soon as the ball passed either of the two 15m lines, their defence went hunting for the ball on attack. Support for the ball-carrier is often at its thinnest in the wide channels, and defence can as easily morph into a devastating counter of its own, turning the tables entirely.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_no_button.jpg)