Will ‘the new breakdown’ encourage the return of the counter-ruck?

Let’s pick up where we left off from my previous article. It concluded as follows:

“Tackled players must immediately make the ball available so that play can continue by releasing, passing or pushing the ball in any direction except forward.” (Tackle 14.7.a).

The key to further improvements in the post-tackle is immediate release: by both the defender(s), fully releasing the ball-carrier and allowing them to make a move to place the ball away from the body; by the tackled player, placing the ball immediately, without any extra movements on the ground and without keeping their hands on it to prevent turnover.

If these articles of rugby law are respected, alongside the requirement to maintain a body position with shoulders no lower than hips, there is every possibility of a new picture of the ruck emerging.

Once the tackled player releases the ball immediately by placing it away from his body, and players from both sides look to enter with their shoulders on a plane level with their hips, the situation at the post-tackle is more likely to be resolved by cleanout (for the attacking side) and counter-ruck (for the defence).

The only time when a defender would be able to get hands on the ball is when he can step across the ball-carrier before his support arrives, and engage.

The counter-ruck has been very much on the back-burner as a method of turning ball over at the post-tackle, but here are some signs of a revival in the 2021 versions of Super Rugby in Australia and New Zealand.

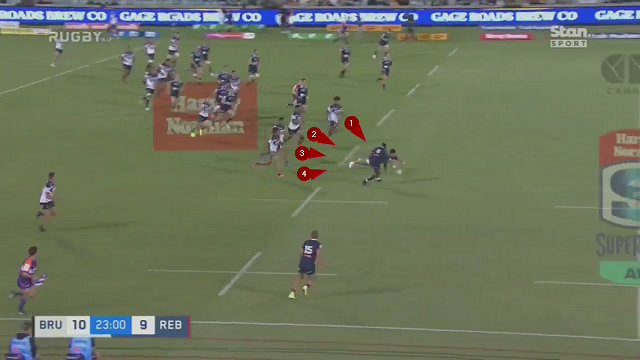

Here is the basic scenario, from a recent Super Rugby AU game between the Rebels and the Brumbies:

Whenever there is a break-down in the attack (such as a loose ball), or the ball-carrier can be trapped behind the advantage line, it is an open invitation for the defending side to counter-ruck instead of trying to pick up the ball directly:

The defence has the advantage in both numbers (four on two) and momentum on to the ball after play breaks down in midfield. All the defensive players are moving forward, attempting to stay on their feet and keep their shoulders level with their hips.

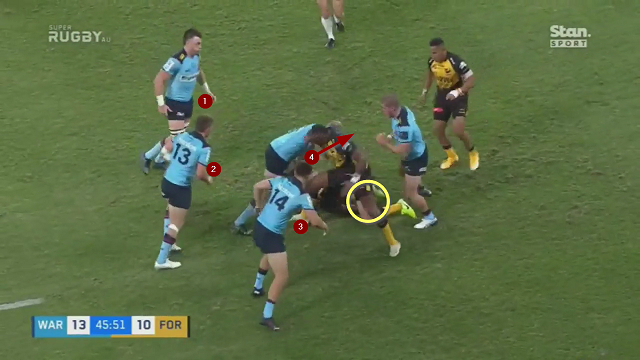

A second example, from the match between the Force and the Waratahs, illustrates how body angles for arriving players upon entry to the tackle site change for the better, and how the counter-ruck tends to expose any errors in presentation by the tackled player:

Force full-back Rob Kearney is caught and outnumbered by the Waratahs defence, and the first arriving Waratah forward wins ‘the battle of the shoulders’ well above hip level:

When the ex-Ireland number 15 goes into a ‘squeeze-ball’ presentation with the ball hidden between his legs, the failure to release is an obvious offence for the referee to penalize.

This is one of the great bonuses from an officiating point of view. When players from both sides do not contest the ball with their hands, any failure to release the ball by the tackled player is clear and obvious:

The Rebels ball-carrier (Wallaby international Matt Toomua) still has his hands on the ball, and is trying to push it back fully five and a half seconds after being dumped on the ground. It is an easy spot for the referee:

The final example comes from the Super Rugby AU game between the Queensland Reds and their interstate rivals from New South Wales:

All three of the first arriving defenders on the Reds side stay on their feet – at least until they have passed beyond the tackle site. The failure of the tackled player to release the ball on the ground is exposed by the Reds number 7 (Fraser McReight, in the hat) when he stoops to pick it up. It is another easy call for the referee.

More improvement in the tackle area can therefore be engineered into the law-book by clarifying the situations in which it is possible for the defender to pick the ball up, or ‘jackal’ for it.

If the defender can only use his hands after all of the requirements for release (by both tackler and tackled player) have been clearly met, there is more chance the ball will be further away from the ball-carrier’ body – not trapped on his chest with the jackal bent double over the top of him. This is the scenario where most of the dangerous head and neck contacts occur.

That change might even persuade the defensive side to adopt the counter-ruck as their weapon of choice, with players committed to staying on their feet all the way through, and beyond the ball.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_no_button.jpg)