About halfway through the recent tournament in France – after a 96-17 rout of Italy at the pool stage – New Zealand head coach Ian Foster suggested that the global game of rugby had reached a crossroads:

“In rugby you have to deal with the challenges that you’ve got.

“The trouble is if you win with a big scoreline, people believe there is no value in it. The value has been massive for us as we put ourselves under pressure the last 10 days for that performance.

“We knew we had to and we didn’t want to give Italy a chance.

“We respect them enough that we had to be in the house. What we have learned is that if we are really focused on preparation and we get it right, and we figure out the challenge in front of us, then we can play good rugby.

“If you look at the South Africa-Ireland game, it was a different game of rugby. The ball was in play for 27 minutes throughout the whole game.

“It was a very stop-start game, very physical, very combative. You saw a different spectacle tonight, and at some point, the world has got to decide which game it would rather watch.” https://www.independent.ie/sport/rugby/rugby-world-cup/the-ball-was-in-play-for-27-minutes-ian-foster-questions-quality-of-stop-start-ireland-vs-south-africa-clash/a630036783.html

Although ‘Fozzy’s’ comment was probably an unfair reflection on the quality of the Ireland-South Africa match (the ball was in play for 32 minutes, not 27), it did gesture towards the difficulty of preserving the attack-defence balance in rugby’s showpiece event. ‘Offence wins games, but Defence wins championships’ as the saying goes, and that has been especially true of the last two World Cups.

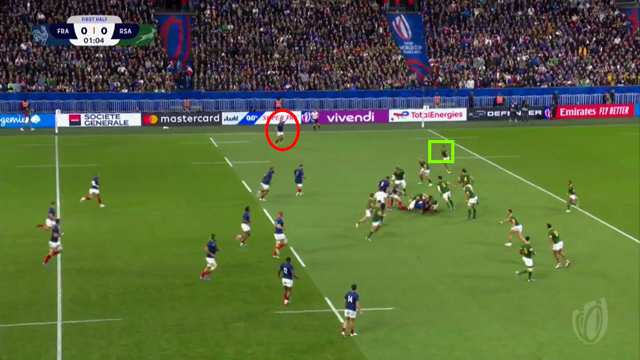

It is worthwhile examining the raw stats from the World Cup to gauge where the game is headed. The first part of this two-piece survey will research key stats thrown up over the course of the competition, the second will then apply them to the direction of a seminal match (France versus South Africa at the quarter-final stage).

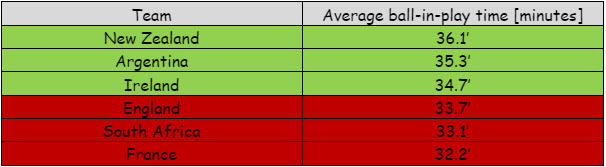

The teams chosen to provide essential background are the four semi-finalists, plus the other two outstanding sides in the tournament (France and Ireland). Those six nations neatly split along either side of a fault-line, between those who wanted to play with the ball (the Pumas, All Blacks and Ireland) and those who preferred to play without it (England, South Africa and France). First, the basics: the following table establishes the amount of ball-in-play time involving the two contrasting sets:

The average ball-in-play time among the possession-based teams was 35.4 minutes per game, the mean among the defence-based sides was 33.0 minutes. The difference became exaggerated when two nations of the same type played each other. For example, the game between Ireland and New Zealand featured a colossal 42 minutes of ball-in-play, the semi-final between England and South Africa only 31 minutes and 55 seconds – a full 10-minute disparity.

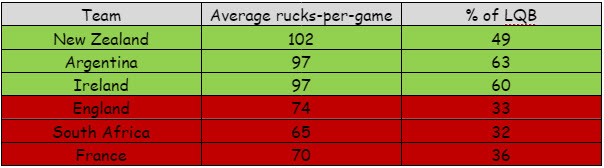

Now let’s follow the thread through a labyrinth of information about the breakdown:

The possession-based teams averaged 99 rucks built per game with a ratio of 57% sub three-second rucks (lightning-quick ball); while the defence-based teams only built 69 rucks-per-game with a 34% proportion of LQB. Where one set prizes continuity and speed-of-phase play, the other tends to avoid the risk inherent in ruck-building and disregards the speed of ruck delivery.

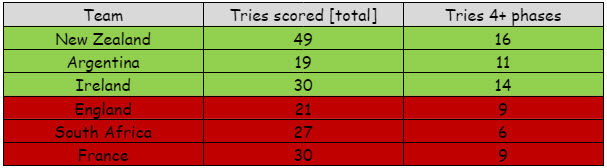

These base figures have a direct ‘domino’ relationship with the number of tries scored, and the number of phases [*] a team is prepared to play through in order to achieve a score:

The attitude to phase-count is particularly clear. The possession-based group averaged 14 tries of four phases or more, the defence-based group only eight.

There were plenty of other ‘spin-off’ stats associated with the two contrasting playing patterns. For example, England, South Africa and France all ranked at the top of the scrum-penalty winning tree with a collective +22 penalties won at scrum-time, compared to a total of +6 by Ireland, New Zealand and Argentina.

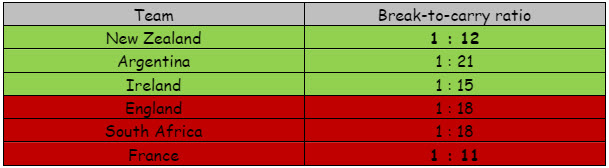

Which pattern is the most efficient? The following table illustrates efficiency via the number of ball-carries required to generate a clean break. The waters in this case are far more muddy than lucid:

Summary

By this standard, the most efficient nations at creating scoring opportunities were one possession-based team (New Zealand) and another defence-based side (France). Both versions of rugby are well-able to generate chances, albeit by different means.

In the second part of the survey, we will examine individual games from the knockout stages where the two approaches were pulling against each other directly, and what the lessons from those matches are for the future of the game as a whole.

.jpg)

.jpg)