Watch a team whose lineout implodes. It happens fast and it happens early. Panic then sets in. The team doesn’t know what to do. Has the oppo broken our code? Has our hooker got a broken arm today? Where should we throw to next?

When a club team has a lineout crisis, they often respond by doing the worst thing imaginable, like a drowning man thrashing about and gasping for breath. They overcomplicate things. They introduce more movement, they delay their throw so the locks can switch positions, they dither and worry until everything is just right. Wrong, wrong, wrong. All they are doing is giving the opposition lineout even more time to get organised against them.

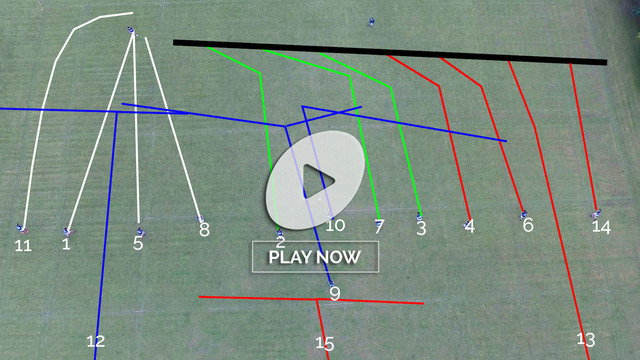

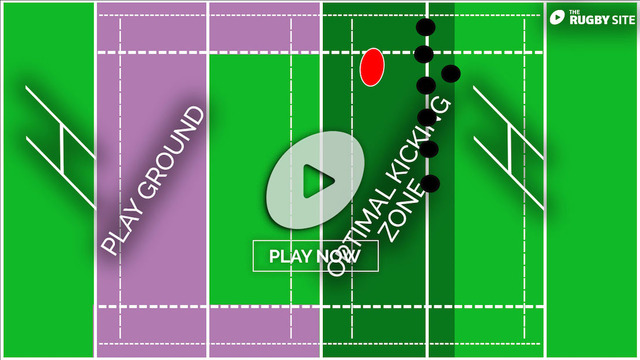

When your lineout starts to go wrong, the best thing is to strip it down to the essentials. Speed is the key. A fundamental of an effective backline is taking away the opposition’s time and space so they cannot get organised defensively. It’s the same for lineout forwards. Don’t give them time and space to get their lifters in the right position.

When we were struggling at Northampton, we would transfer the call on the way into the lineout. We would then get straight into it, assuming that the ref didn’t delay things. Make the call, go in, jump, throw, out of there. Simple, fast and clean. The opposition has little time to react. Be positive. Doubt and worry just create time for the opposition.

Of course it is not always so easy as it sounds. What do you do if the hooker is suffering from a crisis of confidence. You want to win your first lineout of the match to give him a boost. But at pro level you cannot just go in with a simple stock first lineout or you will get it taken off you pretty simply. Victor Matfield was a master at getting in the opposition head early.

In my time at Northampton Steve Thompson would have the occasional crisis with his throwing in. Every hooker does. Keven Mealamu and Andrew Hore can have meltdowns and they are 10-year pros. Sean Fitzpatrick said people always praised him for the accuracy of his throwing but it didn’t start out like that.

When he was a 20-year-old kid, he turned up to training and threw a ball over the top of Andy Haden. He got a look. Next throw Fitzpatrick missed the mark again. Haden picked up the ball, threw it back at Fitzpatrick and said: “Piss off and come back when you can throw properly.”

Fitzpatrick went away. He put a mark on the garage wall and threw a hundred balls a day, every day of the year. It takes discipline. It takes practice. Andre Agassi’s old man made him hit 2,000 balls a day. That’s 730,000 practice shots a year. You will become a better player.

Wally (Steve Thompson) had the same sort of dedication. He would go into the gym with England’s specialist coach Simon Hardy and work and work. He spent a lot of time throwing a rugby ball specific distances from a prone position with while balancing on a Swiss ball, strengthening and engaging the core muscles. Valerie Adams will do similar work as the world’s leading female shot putter.

Over time Thompson became a much better thrower. If he was in a rough patch, the skipper might call a ball over the top. It looks the hardest throw because it has the furthest to go. But for a hooker in trouble it can be the easiest. With his other throws he needs some touch, some distance control. Over the top he can just concentrate on direction. It can also be an easier throw at the end of a match, when fatigue is a factor.

It didn’t come easy to Steve Thompson. As a converted flanker he came late to throwing in. But he worked and worked until England’s lineout became a significant part of winning a World Cup.

So don’t panic and be prepared to put in the hours.

.jpg)

.jpg)