England vs. New Zealand – what a difference a week makes!

As a professional sport of only 24 years standing, Rugby Union is still in a process of rapid evolution. When the sport first ‘went pro’ back in 1995, analysis was still in its infancy. It was very hard to obtain copies of games played on the other side of the world, and those that were available were recorded on grainy VHS video.

Before the 1997 British and Irish Lions tour of South Africa, head coach Ian McGeechan had to work diligently to persuade the Lions tour committee of the value a single analyst, Andy Keast. Keast ended up preparing a video dossier of every key South African player the Lions were likely to meet on tour.

Before the tour match against Natal, Keast said:

“We have provided every Lion with a personal video highlighting his own strengths and weaknesses from earlier tour games.”

“In addition, they each had a one-hour video of Natal, which looked at individuals as well as unit skills; back-row, front five, centres and so on.”

“That way, the player can gain an insight to his own game and work on the minus points, while attempting to advance the good things. In looking at the opposition collectively, the team should attempt to break them down where we think they are most vulnerable.”

This was ground-breaking work at the time. Now the analytical processes are far quicker and more comprehensive than they were back then. Now every elite team will enjoy the services of a team of analysts. Games can be effortlessly downloaded in HD quality and aspects of plays broken down within hours of the final whistle.

The speed and accuracy of the analytical process is crucial at a tournament like the World Cup, where games trip over one another on a schedule that is quite relentless.

Last week I examined how the All Blacks created a new version of their attack in order to defeat the Andy Farrell coached Ireland defensive system

This week England came up their defensive solutions to those patterns in the semi-final in Yokohama. What a difference a week makes!

Against Ireland, the All Blacks looked to play wide through their backs, and then use their forwards off 10 to get the ball beyond the rush of the fourth defender when play came back in off the side-line.

When they tried to implement the same structure against England, the men in white were ready for them:

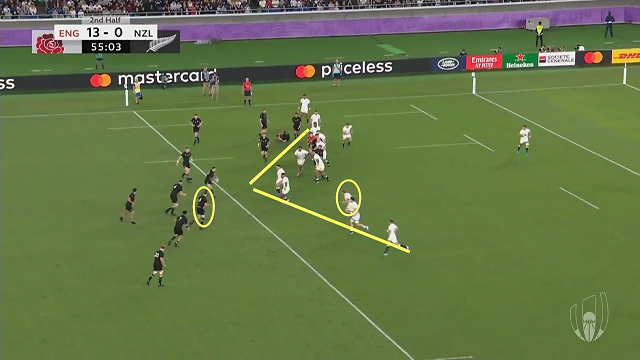

The same pattern is in evidence, with two forwards running close to the ruck off 9 and a pod of three outside a first receiver, here replacement centre Sonny Bill Williams.

The difference is that the head of the England rush is not the fourth defender, but the sixth and seventh defenders – the area where Ireland were soft in the quarter-final.

When the middle man of the pod (Kieran Read) receives the ball, he has already been targeted by England number 7, Sam Underhill (both circled):

Even when the ball was transferred to the outside man of the pod, the English defence at the 6th and 7th defender remained hard and uncompromising. In this example it is prop Joe Marler making a conclusive low tackle on Sam Cane, fully six metres behind the site of the previous ruck:

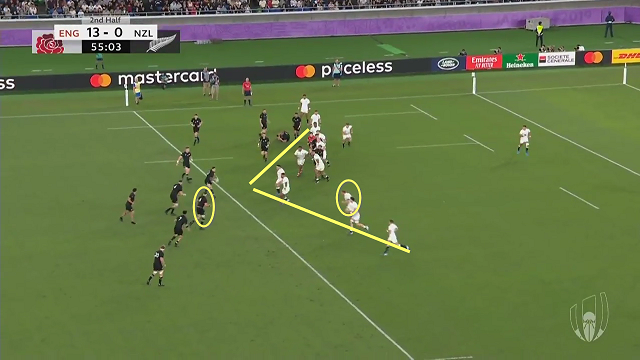

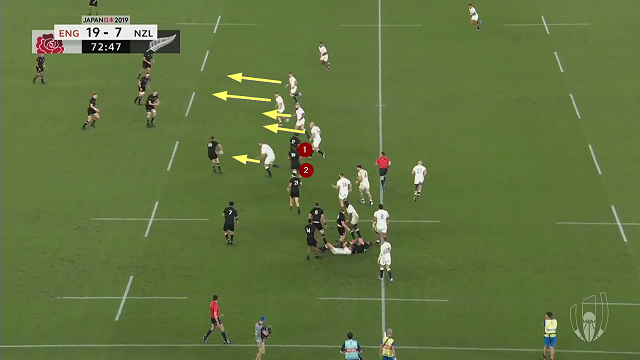

One of the problems with the All Blacks attacking structure is that the two forwards running the decoy lines close to the ruck can be safely written off as ball-carriers by the defence, because they never get the ball. That means that the midfield defenders are free to push up harder on to the first back and the forward pod outside him:

Here it is Beauden Barrett standing at first receiver, and the England forwards close to the ruck simply ignore the two Kiwi forwards (prop replacements numbers 17 and 19) in order to hunt the Kiwi full-back:

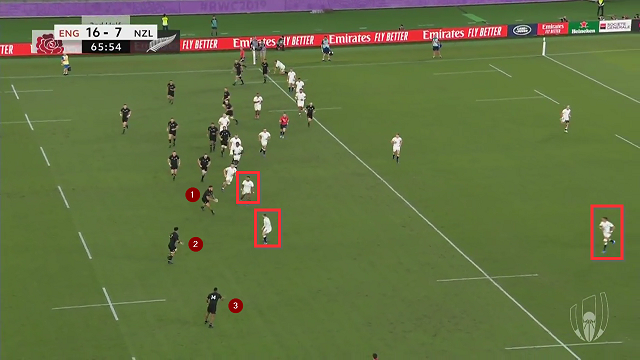

New Zealand tried to vary out of the same pattern, by pulling the rush even further upfield with passes through, or behind their pod of three:

In this instance, the All Blacks have gotten the ball past the high point of the rush by passing in behind the midfield forward pod. The problem now becomes the personnel they have left to use the ball on the right-hand side of the field – a prop (Angus Taavao) is trying to throw a long pass off his left hand towards Ardie Savea and Sevu Reece.

There are three England backs waiting for them:

All of the Kiwi backs bar Reece had been used on phases shifting the ball out towards the left, so this phase has become a mismatch in the defence’s favour!

Likewise, even when the ball was transferred successfully through the pod and out the back, past the point of the rush, the defence was still able to adjust and make a tackle further upfield than the site of the previous ruck:

The ball goes through Brodie Retallick and out the back to Sonny Bill, but the depth needed to make the transfers simply pulls the D to another breakdown point where they are gaining, rather than losing metres.

The first World Cup semi-final in Yokohama was an object lesson in how quickly information is gathered and assimilated by elite teams. Only seven short days separated the All Blacks’ attacking success against a rush defence versus Ireland and their failure against England’s version.

In the meantime, England had learned where and when to rush, and how to avoid the soft spots from which Ireland had suffered so badly. Their adjustment cost the All Blacks the historic opportunity to claim a ‘three-peat’ of successive World Cup victories.