What is the best defence at lineouts?

There are always plenty of ongoing debates on defence: how many players should defend in the backfield, and how many in the front line? Where should the scrum-half defend? Who should play on the edge of the short side defence? How many defenders should look to ‘wrap’, or change sides after a ruck? We could add many more.

The coaching possibilities always seem to multiply when there is more (enforced) space between the two teams, as there is from a lineout. All of the non-combatants at a lineout are required to stand 10 metres back, and many different philosophies have evolved to cover the distance between the forwards in the lineout, and the remaining defenders 10 metres away.

It is an important space, which switched-on attacking teams will often look to exploit if they feel there is any weakness in connection between the two lines. The two players mainly responsible for that connectivity are:

(1) a defender in the ‘tram-lines’ or five-metre zone close to touch: Law 18.15 says, “The non-throwing team must have a player between the touchline and the five-metre line. The player stands two metres from the mark of touch on their team’s side of the lineout and two metres from the five-metre line.”

(2) a receiver who is the defensive equivalent of the scrum-half: Law 18.16 says, “If a team elects to have a receiver, the receiver stands between the five-metre and the 15-metre lines, two metres away from their team-mates in the lineout. Each team may have only one receiver.”

There are two basic theories about who these players should be. The more common policy at professional level is to position the scrum-half in the tram-lines and the hooker as the receiver, typically towards the tail end of the line (the ‘tail gunner’).

The hooker is ready to fill a midfield defensive role in subsequent phases, while the number 9 will probably be required to defend on the short-side edge initially, and drop into backfield duty thereafter.

The second policy shifts the number 9 into the receiver role, with the hooker stationed in the tram-lines. This system tends to increase the pressure on the opposing outside-half (the scrum-half can be quicker to rush) and suits a subsequent pattern where the number 9 is required to play in the ‘boot-space’ behind every ruck. Short-side defence can take longer to organize with the hooker coupled to the wing for the initial phases.

Let’s take a look at these patterns in action, along with some variations, in the recent Trans-Tasman game between the Highlanders and the Force. The Highlanders scored the first try of the match, with the Force using a variant of the first defensive pattern:

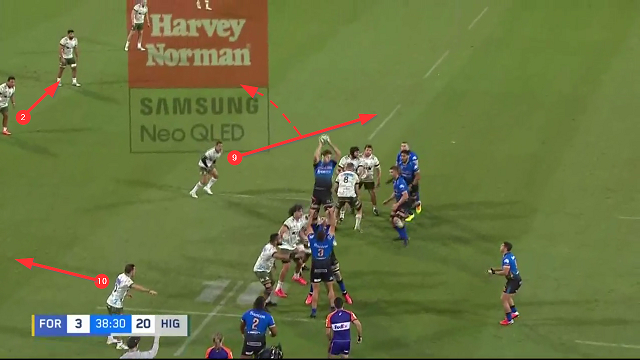

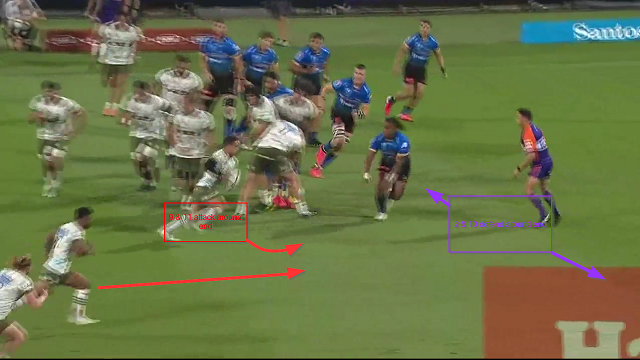

The Force number 9, Pumas international Tomas Cubelli is in the five-metre zone, while the hooker Feleti Katu’u is playing a hybrid role as ‘tail-gunner’:

.png)

The Force are shaving the margins down to the bone in this situation. They want Kaitu’u to both support the tail contest in the air, and then be able peel off to mark the Highlanders number 9 Aaron Smith as he rolls around the end of the line.

The task proves too much, and the connection between the hooker and the first defender in the back-line zone 10 metres away is lost. It is an instructive moment on attack: the Highlanders are looking to push both Smith and their blind-side wing (Jona Nareki) through the gap between Kaitu’u and the first back-line defender:

Towards the end of the first half, the Force got their own back:

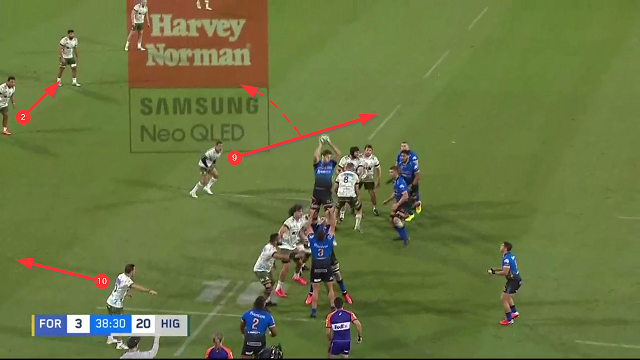

The Highlanders are using a variation of the second defensive pattern:

In this instance the first five-eighth starts in the five-metre zone and the hooker in the 10 channel – more commonly these two players would swap roles. But the key is the use of Aaron Smith as the defensive receiver. His role is very different to Kaitu’u’s for the Force.

Where the hooker is looking to defend tight – either lifting the tail jumper or defending the 9 around end – Smith’s role is to shoot out at the opposition number 10.

This creates a new problem for the defence. There is more danger of a disconnect occurring between Smith and the forward turning out of the lineout inside him, than there is of a disconnect between Smith and the back-line advancing on his outside.

The form of attack changes with it. The ball goes all the way out to the Force number 10 rather than staying with 9. He drags the space around Smith, before passing back in to the blindside wing – again the key strike player.

There are plusses and minuses to both systems, and both require a slightly different use of the blind-side wing to find the most sensitive area of weakness. The choice of pattern for the defence depends mostly on the defensive ability of the hooker, and how you want to use your scrum-half in subsequent phases: out on the edge and/or in the backfield, or as an organizer behind the ruck?