Why defence won South Africa the World Cup

The Alabama College Football coach Paul ‘Bear’ Bryant once famously declared: “Offence sells tickets, but Defence wins championships”. The veracity of that statement was certainly proven at the semi-finals of the Rugby World Cup in Japan.

Very few neutral spectators would have bought tickets to the game between South Africa and Wales if they had known the fare on offer. Probably the two best defensive sides in the tournament kicked the ball away no less than 73 times between them, and the there was little in respect of attacking flow on offer.

One day before, the two best attacking teams in the competition – England and New Zealand – had served up spectacle which the neutral might be tempted to pay to watch even as a repeat. It was that compelling.

Yet when push came to shove, it was defence which triumphed in the final, just as it had so notably in 1995, when South Africa shut out the best attacking team – the All Blacks, Jonah Lomu and all; in 1999, when Australia conceded only one solitary try on their way to the Webb Ellis trophy; in 2003, when Phil Larder produced a defence which topped all of the meaningful global ratings in the two years prior to the World Cup to drive England to their one and only World Cup success; and in 2007, when South Africa achieved their second victory while conceding a meagre 13 point average per game in the knockout stages of the competition.

Ultimately it was defence which proved to be South Africa’s trump card for a third time at the biggest tournament in the world in 2019. The bricks in the Springbok wall were built methodically by their defensive coach Jacques Nienaber, a long-time confederate of head coach ‘Rassie’ Erasmus at Western Province, the Stormers in Super Rugby and Munster in Ireland.

The subtle nuances behind Nienaber’s version of the Rush Defence are not always appreciated. It is not just a matter of running as hard as you can upfield play-in, play-out with the avowed intention of laying the nearest opponent out for the count.

A long, two-minute sequence at the beginning of the Boks’ pool game against New Zealand set out Nienaber’s stall perfectly.

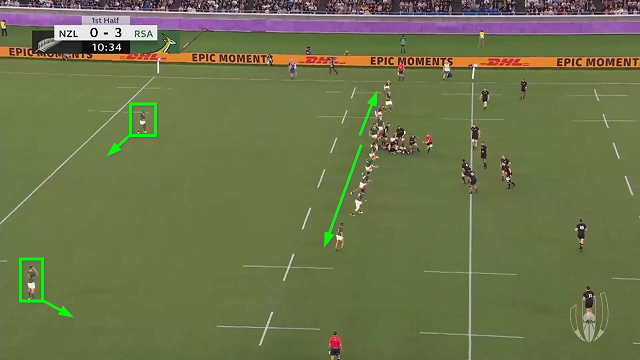

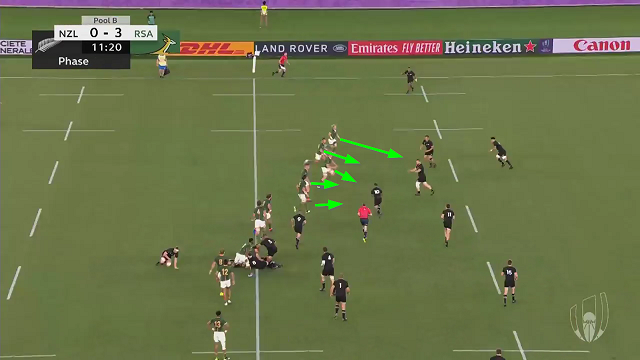

Here is the basic shape of the Springbok D at midfield:

There are 13 men on the line and just two in the backfield, and the 13 up front are all compressed into a space only 45 metres wide. There is no intent to keep width and mark up on all of the All Blacks’ attackers, and the open-side wing Cheslin Kolbe is looking in towards midfield as the ball comes out.

While the line has shifted down towards the site of the ruck, the backfield has rotated in the other direction, on the understanding that a potential kick can only be made out to the Springbok right.

The advantages of this defensive structure can most clearly be observed when the ball is moved out to one edge of the field. On the way back, the D is free to tee off an ‘fly’ upfield:

Because of the tight spacing between defenders, there are always two men in the tackle, which leaves one free to release and contest the ball after the tackle has been completed. Because of the line speed generated, the site of that tackle is 7 metres behind the previous ruck. On the far edge of the field, the last defender (#9 Faf de Klerk) jams in to remain connected to the rest of the line – he starts his run five metres outside the 15m line and ends five metres inside it.

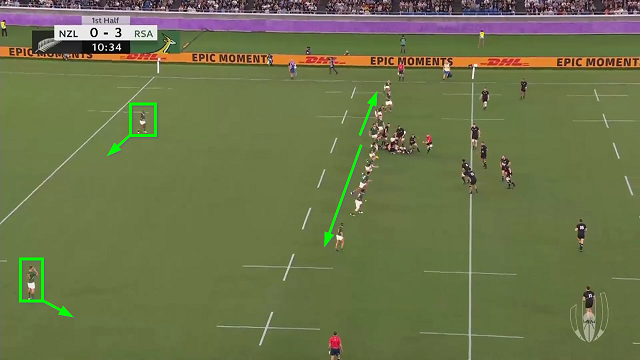

Defensive momentum developed even further on the next phase, causing a handling mistake:

Now the site of the tackle is 10 metres behind the previous ruck, and the South African presence over the ball means another six seconds before Aaron Smith can play it again. That is slow ball indeed for a high-octane attack like that of the All Blacks.

Because of the slow delivery, the rush line is quicker and de Klerk’s angle infield is even steeper and more acute. Another phase, another error:

The Springboks are happy to cut New Zealand right wing Sevu Reece free on the far side-line, knowing that their line-speed will count for more.

In the process of seven phases, the New Zealand attack has been pushed back 20 metres, forcing the kick:

By the time Richie Mo’unga is ready to launch the kick, Makazole Mapimpi has already advanced out of his backfield zone and de Klerk has shifted across to help him.

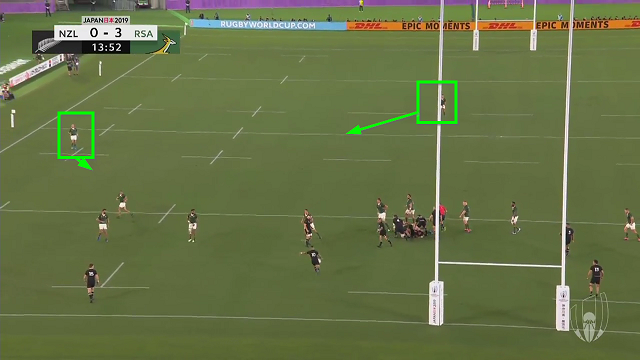

The finesse in Nienaber’s set-up can best be appreciated when the same sequence was repeated only a couple of minutes later:

Cheslin Kolbe is playing the same role as de Klerk on the other side of the field, jamming in hard and cutting the last two attackers loose outside him in the knowledge that they will never receive the ball!

As soon as Nienaber’s defence smells ‘kick’, the picture changes:

With the clearance kick bound to be made out to the New Zealand left, the South African backfield has already rotated in that direction to receive it. Despite enjoying three and a half minutes of near-continuous possession, the All Blacks find themselves 60 metres closer to their own goal-line as boot makes contact with ball.

Defence has its own subtleties and its own intelligence, and can be used as a legitimate method of advancing down the field. Perhaps it deserves to sell more tickets than the more obvious plays on attack. ‘Bear’ Bryant would certainly be silently applauding that thought from the sidelines.