Why does defence look so different in the modern era?

Why is there a need to keep pace in the observation, and explanation of the game of Rugby? Many of the understandings in the game still derive from the amateur era, or the early days of professionalism. It is only natural, because most of the commentators tend to be ex-players whose careers may have ended 10 or even 20 years previously.

In fact, the sport is still in its professional infancy and the growth spurts tend to be very rapid as a result. Nowhere is this truer than in the area of defence. World Cup winning captain Martin Johnson once gave me a graphic description of a try scored by the All Blacks against England back in 1997 at Old Trafford:

“There was a three-man lineout on our 22. Robin Brooke won it and within two passes the ball was in the hands of Frank Bunce in the centre. As he took the tackle the ball squirted out and I went through and tried to dive on it, but their scrum-half Justin Marshall managed to get the ball away."

“Lying on my back, all I could hear was our hooker Richard Cockerill screaming at the top of his lungs for defenders to join him back near touch where the lineout had taken place. He was turning the air blue with swear words and waving his arms about, but as I got up, I saw that all of our forwards were within ten yards of me. They had run towards the ball as soon as Bunce made contact and it felt as if a stone had dropped through my stomach: ‘Bugger me, they are going to score’. That’s what we did in those days, we all followed the ball automatically and hit rucks, we didn’t drop into defensive channels and mark the width of the field."

“New Zealand were way ahead of us in their thinking about the game and they were able to use their ball-handling forwards mixed in with the backs. We had no idea how to defend because we still thought of forwards and backs as separate units – as forwards we were there to pile into the ruck and win the ball, not think about what the opposition were doing and where they would attack us next.”

As ‘Johnno’ implies so eloquently, it takes a lot of time for understandings to change. The trends set on defence by the current world champions South Africa can be used as a testimonial. Let’s take a simple example from one of their Rugby Championship games against Argentina to illustrate just how much the concept of defence has changed in the professional era. The start-point is Johnno’s favourite, a midfield punch from lineout by the Pumas:

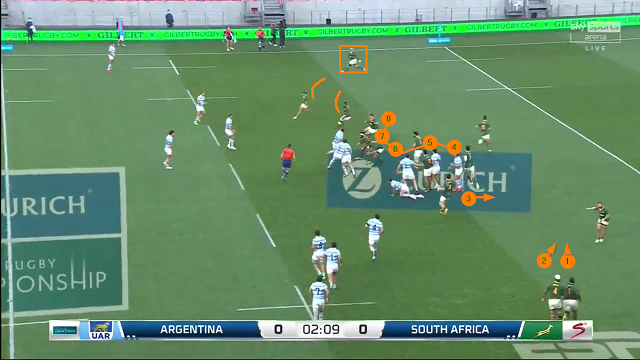

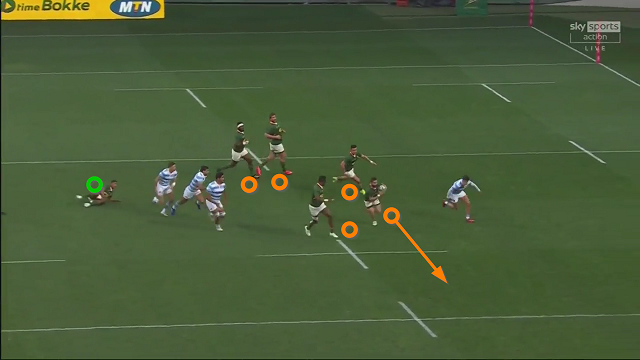

From the attacking viewpoint, it’s a better-than-average first phase. The Argentine number 13 falls forward in the tackle and the ball is lightning-quick, under two seconds from presentation to pick up and pass by the scrum-half. Now let’s look in detail at the situation as it develops on second phase, and how the level of defensive response has moved on in 26 years of professionalism:

The red circle represents Johnno’s ruck perimeter. All of the forwards would have been expected to be within its bounds in the amateur era. But in the snapshot, there are five South African forwards outside it – three who have wrapped around to the far side, and two who are being directed into position on the near side by the Springbok scrum-half Cobus Reinach.

Now let’s move forward to the picture as it might have looked in the early stages of professionalism around the turn of the millennium:

“4” (Lood de Jager) and “5” (Franco Mostert) would join a steady trot around the corner by the other forwards (“6”, “7” and “8”), and enable the two backs beyond them to drift out to link up with the last defender (in the rectangle).

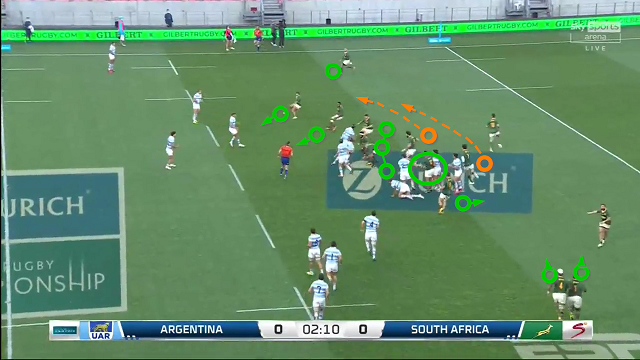

Now let’s see what actually happens in a fully-committed rush defence in the present day:

The South African midfield continues to rush on second/third phase despite the availability of lightning-quick ball for the attack, and they do not attempt to link up with the last defender. That job is left to de Jager and Mostert, who have to run all the way from inside the perimeter of the first ruck out to the far side-line, to become the defenders inside the last back (Cheslin Kolbe).

There are effectively, two layers of defence: an aggressive rush line composed of backs, and a second layer of forwards drifting in behind them.

Here is another example, with play moving from side to the other in one single phase:

The midfield backs (centres Damian de Allende and Lukhanyo Am) rush straight upfield and it is left to three big forwards (de Jager and Mostert, plus number 4 Marvin Orie) to fill in behind them, connect to Kolbe and force the mistake, a forward pass. Compared to the amateur days and even the early period of professionalism, the level of aerobic activity demanded from tight forwards (and big back-rowers) is huge. In fact, there is no comparison.

Let’s finish by examining a different version of the same theme, this time from scrum:

The upfield rush demands that the South African left wing Aphelele Fassi defend no wider than 5-7 metres beyond the far post – so who is going to cover the space to the far side?

The answer becomes a lot clearer in the view from behind the posts:

The last defender (full-back Damian Willemse) is on the ground, but no less than five Springbok defenders have recycled themselves into the space beyond him, and they swarmed to the loose ball: number 6 Siya Kolisi, 10 Handre Pollard, 12 Frans Steyn, and scrum-half Reinach, who followed the ball all the way from the ‘wrong’ side of the set-piece to pick up the fumble and run away to score.

Modern rush defence works because of the aerobic ability of the second layer of defenders to fill in the gaps left by the first line as they shoot up and look to disrupt the play. The days of forwards automatically committing to the ruck, or joining a steady but passive drift across the field, are long gone. Nowadays, everyone is expected to run further and faster, as defence is increasingly weaponized as the main form of attack.