It became England’s one and only pathway to World Cup glory back in 2003. With the final game against Australia still seething and simmering in the balance at the end of extra time, England produced a lineout move designed to set up Jonny Wilkinson for a drop-goal in centre-field:

Jonny Wilkinson Drop Goal RWC Final 2023

As England scrum-half Matt Dawson comments on the sound-track,

“The whole world knew he [Wilkinson] was going for a drop-goal. So, if you were in the Australian side, you would be sitting in the blocks, twitching [and ready] to go, to charge that kick down.

“So, my thoughts are ‘they are going to be twitchy, I might just dummy the trigger on the gun’.

“As soon as they [the defensive rushers] twitch and [have to] go back, any scrum-half will tell you that is the time to pass the ball.”

The keys to drop-goal success are three-fold:

2.Scrum-half action around the fringes to straighten the attack and keep the defence honest.

3.Extra bodies committed to securing the breakdown, typically three or four, and leaving the width of the attacking line stripped down to a bare minimum.

In this example the process of centralization is achieved via a ‘zigzag’ pattern, with Dawson first dummying and breaking to the left of the ruck, then England bringing the ball back to the opposite side through their captain Martin Johnson to centralize the position for the ‘droppie’ to come. Both runs are made close to the ruck with four or five bodies committed to cleanout, to provide an extra layer of protection.

It is still a mystery why more rugby union teams do not use the drop-goal as a primary method of scoring points. In Union, the value of the ‘droppie’ has remained constant at three points. In its sister code League, it was first reduced from four points to two back in 1897, then from two points to one point in 1971. League probably has it right in terms of the value it offers to the game as a spectacle, relative to a try.

Roll the clock forward 20 years later, and Steve Borthwick’s England had been struggling to score tries in the preparation for the World Cup in France. The drop-goal offered them an invaluable ‘out’, and a reliable method of scoring points against their first-round opponents Argentina – especially after they lost Tom Curry to a red card in only the third minute of the match.

England #10 George Ford knocked over a trio of droppies in the first half against the Pumas, giving his team a comfortable scoreboard cushion to defend in the second period.

The first occurred in the 27th minute and followed a similar pattern to its famous counterpart in 2003:

There are two centralizing runs from lineout, one a tackle-busting first phase by Manu Tuilagi, the second a ‘settling phase’ by prop Ellis Genge after a short snipe around the fringe by scrum-half Alex Mitchell. The centralized position is more important than the ground gained or lost, in order to open up the posts for Ford’s kick and give the widest-possible margin for error.

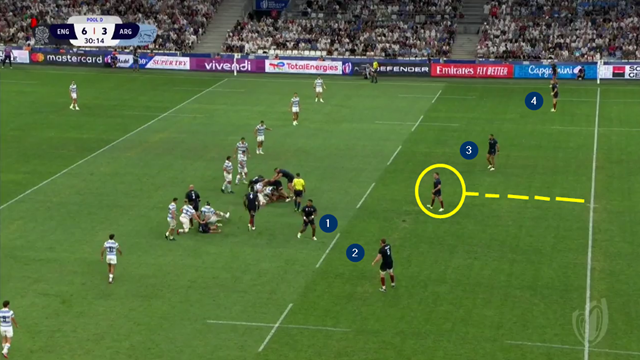

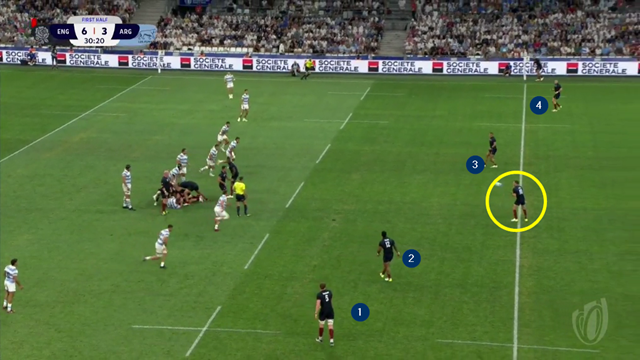

Ford’s second three-pointer occurred four minutes later, and once again it was triggered after only three phases from lineout on the Argentina 22. After an initial run by #8 Ben Earl, the key is again the threat of a ‘scoot’ around the infield edge by Mitchell:

There are four players attending each of the two rucks, which means that the play will be both ultra-simple and ultra-secure. In both the screenshots, the Argentine defence outnumbers the English attack on both sides of the breakdown, so ‘max protection’ of the ruck ball has been preferred at the expense of a quick delivery and a structure which enables sustained attack. George Ford drops back roughly seven metres in order to kick the goal from halfway.

The third drop-goal followed the same formula from a position closer to the poles: a lineout starter, followed by three centralizing phases with four-man rucks instead of the usual three-man breakdown (ball-carrier plus two cleanout supports) emphasizing ball-security and creating a comfortable pocket for Ford’s kick:

Summary

The drop-goal remains an exploitable anomaly in rugby union law-making, one which was addressed by its sister code more than 50 years ago. It is still worth three points, or 60% of the value of a try, whereas in League it is only worth one point.

Three phases from lineout are typically sufficient to centralize the ball in front of the posts. Scrum-half threats around the fringe helps attract the inside defence and give easy ball-protection with an extra player (or two) added to the cleanout. If your kicker is competent, it is a simple and risk-free method of keeping the scoreboard ticking over. The only surprise is that teams wait for big occasions like the World Cup in order to put it into practice.