Angling for an advantage: scrum & maul at England vs. USA

There are two old adages which can, at times, both be appropriate for situations on a rugby field. On the one hand, “The shortest distance between two points is in a straight line”; and on the other, “Take the path of least resistance”.

In the professional age, the second statement is arguably more important. The reason is that the global standards of physical conditioning are rapidly levelling up. At the 2015 World Cup, the Uruguay side was described as ‘the last of the amateurs’. Four years later in Japan, things are very different, with Uruguay managing to turn over one of the World’s top ten teams, Fiji, in their opening match.

Over the last World Cup qualifying cycle, the top 15 Uruguayan players have turned professional in the American Major League, and a former Wales and British & Irish Lions conditioner, Craig White – plus his team of four British assistants – was hired to prepare the 31-man squad in the course of the four months preceding the tournament.

White is credited with many of the physiological improvements which led to Uruguay’s historic 30-27 victory over Fiji. In relation to the two adages with which the article began, this means that most the forms of improvement at elite level tend to occur not so much in a straight line, and directly through the opponent, but by smart methods designed to find the path of least resistance, and a way around him or her.

In the round two World Cup group match between England and the USA, the American tight forwards outweighed their English counterparts by an average of over 2 kilos per man. In the event, it was nonetheless the England tight five who clearly dominated the power-based set-pieces of scrum and driving maul.

They achieved that dominance through excellent technique, and a superior knowledge of how and where to deploy their power at the set-piece. Instead of driving in a straight line, they first explored the path of least resistance by the smart use of angles.

Let’s take a look at what this means, firstly at scrum-time:

The asymmetrical nature of the packing in the front row at a scrum – with four players packing in ‘tight’ between two opponents, but the other two ‘loose’ on the side – allows for the skilful use of angles by props and hooker.

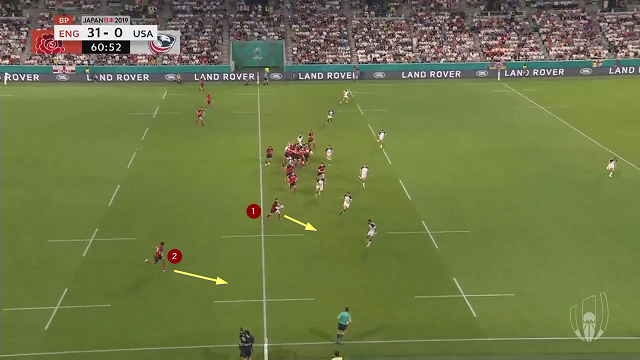

In this instance, England initially head for the path of least resistance by looking to drive the scrum from right to left:

England’s forwards are driving straight, but they are also on a diagonal shift – particularly in the ‘pod’ of forwards behind Dan Cole on the tight head side (number 3, 5 and 7). All the body shapes of the England tight forwards are coherent and angled along the same axis, whereas each of the USA forwards opposite them are applying their force randomly, in different directions.

Of course, this effect could not have been achieved if the drive had been exerted straight forwards and without any subtlety. The point is to destabilize the opposition by changing the angle of attack first, then demonstrate that your cohesion is superior as the set-piece develops. At the end of the scrum the USA forwards have disintegrated completely, and everyone has either collapsed or lost their bind.

England were also quite capable of moving the scrum the other way, in order to create an advantage on a first phase strike for their backs:

England are still going forwards as the law requires, but they are also doing it on a left to right axis in order to promote their tight-head:

Promotion on this side takes the covering USA forwards further away from the ensuing play, and gives the two England backs on the right an attractive attacking space to run into.

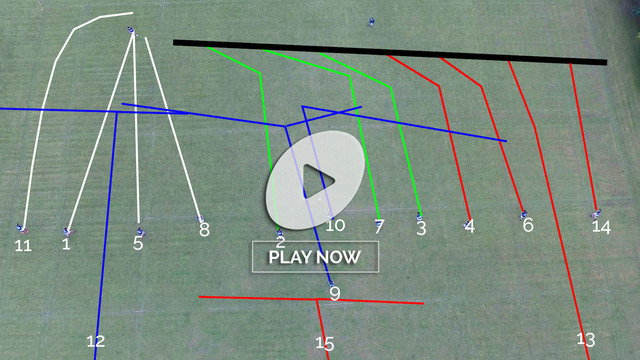

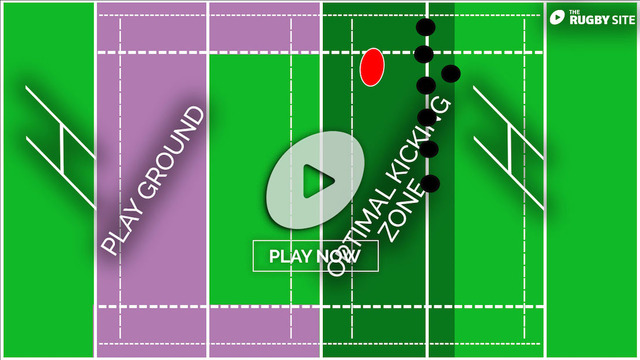

The same emphasis on a change of angle preceding the application of power was present at the driving maul from lineout. Here is England’s second try of the game in the 25th minute:

The idea is not to drive straight through the meat of the Eagles’ defence – their big men (numbers 3, 4 and 5) on the left side of the maul. The ball is shifted away to the opposite side first, to leave them with no role to play. The drive starts on the 15-metre line, but the try is scored at a spot three metres to the left of it:

England only apply the power directly forward after they have cleverly sidestepped the initial challenge by the three principal American maul defenders. The passage to the goal-line after that initial use of the angle is almost completely unimpeded.

Whatever can be done to the left, can equally well be applied on the right!

Compared to the first example, this is a much longer and more complicated sequence. At the beginning of the maul, the three main Eagles’ defenders (again, numbers 3, 4 and 5) are all walling off the angle England want to take, so the initial task is to advance the spearhead of the drive beyond them and force the trio to regroup:

Once 3, 4 and 5 are all out of play, the angled drive can proceed effortlessly on its chosen track; from right to left, and with the assistance of a couple of backs (numbers 12 and 14).

As the angle develops and the USA tight-head prop and second rows are marginalized, there is effectively no resistance remaining in front of the drive:

A drive that started near the 5-metre line ends up with the 15-metre line clearly in view. The same theme which dominated the scrums, operates in that other power set-piece, the driving maul. It is not just the quantity of weight and power being applied, it is more importantly, the technique used to deploy it. The use of the angle is the key to unlocking ‘the path of least resistance’.

.jpg)

.jpg)