Changing perceptions at scrum-time: All Blacks-Pumas – the Sequel

They say that the sequel is never as good as the original, at least in movie terms. In professional rugby, and especially in a series of matches against the same opponent, the challenge can be to alter refereeing perceptions from previous encounters. In other words, to demonstrate that the original is not always the best.

This was the challenge thrown down to the All Black scrum after their loss to Argentina, which I examined in this previous article.

The loose-head side of the New Zealand front row suffered grievously in that game, both from the clever (and legal) binding protocol followed by the Pumas tight-head prop Francisco Gomez Kodela, and also from the highly illegal activity of the flanker on Gomez Kodela’s side (Marcos Kremer), consistently releasing his bind and slamming into Joe Moody’s hip.

So, the challenge facing the All Blacks’ coaching staff and players was to reverse the perception of the left side of their scrum. They accomplished this in definitive style.

There was a new official for the game, with Nic Berry replacing Angus Gardner as the man with the whistle. Refereeing perceptions in areas which are highly technical and complex, like the scrum, are often established by the first event at the very beginning of the game.

It tends to leave a strong visual stamp on the referee’s mind which filters into future 50/50 decisions, consciously or unconsciously. Therefore, it is vital to create the picture you want at the first set-piece.

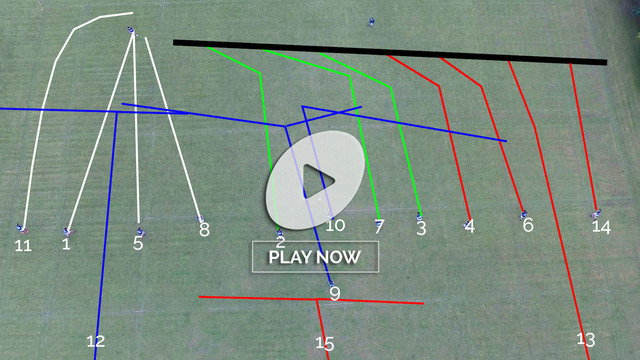

The All Blacks knew that they had to do some powerful work in this area in order to change the impressions left by the previous encounter. Here is the first scrum in Newcastle:

The problems Joe Moody had experienced in Sydney were twofold: (1) Gomez Kodela was able to keep moving forward as an angle developed towards the centre of the scrum, and (2) Kremer was able to drive off the flanker supporting Moody, then pull away his left arm bind.

In the sequel, the picture being painted is very different. Gomez Kodela had been replaced by the less experienced Santiago Medrano for this game, and Medrano is not able to pack as low as his forebear. When the angle begins to develop, he is caught high and ends up facing towards the far touch at 90- degrees:

When Kremer releases his bind to assist the prop in front of him, he is helping out a man in trouble, rather than a man in a stable pushing position.

Nic Berry called the Pumas’ scrum captain Julian Montoya across to him after this scrum, which ended in a penalty to the All Blacks:

“Julian – two things there, okay?

“Your tight-head has gone in on an angle. Also, your 7 is jamming up into their loose-head.

“I don’t want the 7 to do that”.

At this point, the All Blacks had effectively won the battle of perception at scrum-time for the rest of the game.

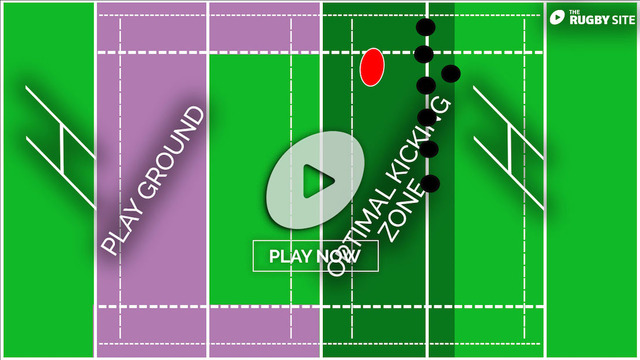

Let’s look at the consequences at the next Argentine feed, at a scrum near their own goal-line:

Joe Moody’s bind is long and undisturbed, and Marcos Kremer stays nailed to the side of the scrum as the Pumas retreat. That in turn enables Sam Cane to push off and make an aggressive tackle when the ball is picked up at the base.

The next example represented an even worse outcome from Argentina’s point of view:

As long as Joe Moody is able to bind long with his outside arm, and keep that bind intact for the duration of the scrum, he is a threat to his opposite number:

Although Kremer rather apologetically comes up at the end of the play, he has not been able either to influence the angle of Moody’s drive, or pull away his left arm bind, which has now reached all the way around to the back of his opponent’s shorts.

The result is another penalty to the All Blacks, and an even more damaging blow to Argentine morale.

It all starts at the very first scrum. In fact, it probably started even earlier, with All Black coaches drawing attention to Kremer’s activities at meetings with Nic Berry in the build-up to the match. Manage perceptions of the set-piece at the beginning, and you will get the outcomes you want as events unfold.

.jpg)

.jpg)