Constructing the lineout drive as an attacking setpiece

At the top level of the game, the lineout drive has become the set-piece weapon of choice for many successful teams, especially in the Northern Hemisphere. It is no coincidence that the Exeter Chiefs (the current champion club in England) run it particularly well, and it is strong enough to form the basis of their game.

Brendon Ratcliffe’s valuable starter series on the lineout drive, demonstrates the fundamentals of setting and developing a good lineout drive.

Brendon’s two modules break down the three basic phases of the driving maul:

• Setting the platform – establishing the blocking front

• Adding the second layer & timing the ‘go’ call

• Rebuilding the blocking front & sustaining momentum

At international level, the best driving lineout in the world has probably belonged to Ireland over the past few years. Ireland have become expert at taking what the opponent gives them and manipulating the maul upfield.

There were two very clear examples of Ireland’s praxis in the first half of the famous game against the All Blacks at Soldier Field in Chicago back in November 2016. This was the one and only occasion where Ireland have beaten New Zealand, and one of the most important aspects of that success was the strength of their lineout drive after All Black prop Joe Moody had been yellow-carded in the 7th minute of the match.

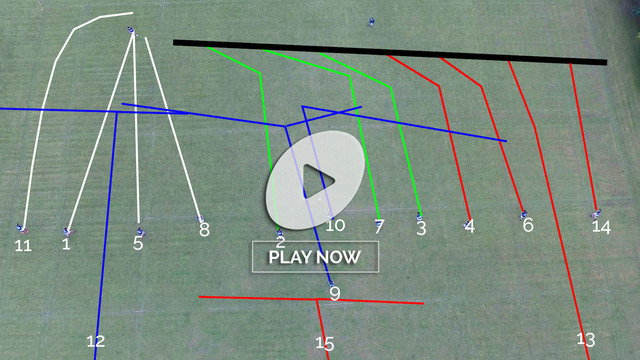

Let’s take a look at how Ireland controlled the three phases of the drive at two lineouts in the 8th and 9th minutes of the game. I’ll use the earlier example to isolate particular phases of the drive, while the second instance will show how it works in full flow.

Phase One – setting the platform

The lineout drive begins with the two lifters in the receiving pod, positioned on either side of the catcher. In the first part of his module, Brendon Ratcliffe stresses the importance of the lifters disengaging from the lift as quickly as possibly in order to get into strong driving positions.

Brendon recommends that each lifter ‘pop’ his inside shoulder (and foot) past the receiver in order to adopt the optimal position. While this is indeed the ideal, at the higher end of the game it is seldom possible!

Typically the defenders will try to jam into the two gaps on each side of the receiver as the catcher returns to earth:

If the two lifters cannot advance their inside foot/shoulder past the catcher, the most realistic aim is for them to angle across his back and connect together, providing a water-tight seal against any defender who wants to penetrate on to the ball itself:

Here the two Irish lifters have worked their way across the back of the receiver at an angle of almost 90 degrees and they are firmly connected. At this stage of the maul, that tight, angled seal against any possible penetration is the most important aspect of the set-up.

The three-man blocking front is rarely perfectly straight. As at the scrum, one of the lifters/blockers is always slightly more advanced than the other, and this gives a vital clue as to the direction of the drive. It will not be straight ahead, it will be offset through one particular side of the defence:

Right from the catch, the outside lifter (Devin Toner) is more advanced than his inside counterpart (Jack McGrath), so this drive will be aimed at the open-side side of the New Zealand maul defence.

The second layer and the ‘go’ call

You want your most powerful driving players in the second layer of the maul, to provide the engine to move it forward. In the first screenshot, Ireland start with their scrum-half Connor Murray at the front of the line, which allows their powerful number 8 forward C.J. Stander to enter from the halfback or “+1” spot directly behind the catcher.

He is joined by tight-head prop Tadhg Furlong, who enters to his right in behind Toner and the ultimate direction of the drive.

As the drive develops and the New Zealand defence begins to fragment, it is Furlong’s head which appears at the head of the maul:

The ‘go’ call was probably made sometime around the second screenshot, when a quick body-count would reveal only five All Black forwards committed to the maul – with Dane Coles and Sam Cane still detached in fringe defence and Joe Moody watching from the bench!

Rebuilding the blocking front

After Furlong (circled) is finally peeled off the head of the drive by Owen Franks, C.J. Stander (arrowed) is on hand to take up his position and rebuild the blocking front without any loss of momentum:

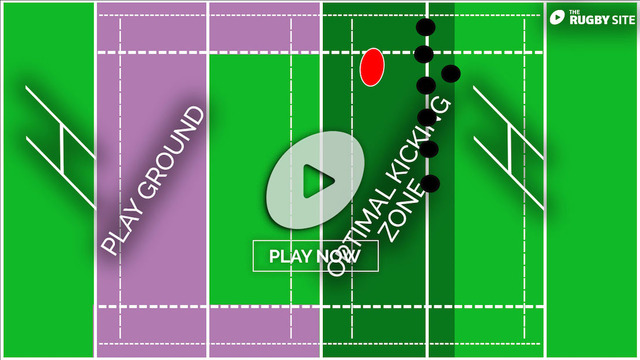

Putting it all together for the try

Ireland won a penalty from this drive, which allowed them to launch a second attack from a position only 5 metres from the New Zealand goal-line:

The main difference between the two drives is that the second one is angled towards the short-side rather then the open-side of the field. After the seal across the back of the receiver is formed, two Irish forwards appear on the left of the maul to drive it through on that side without significant opposition:

Once again, Furlong and Stander are the engine in the second layer which powers the drive forward, with Rory Best (in the white hat) steering the ship behind them.

Techniques vary according to the level of the game at which you are operating. But the principles underpinning those techniques remain the same: (1) convert your lifters into blockers quickly and seal the space in front of the receiver, (2) pick a side for the drive and deploy your main driving power in the second layer, and (3) rebuild more quickly than the defence as blockers are peeled away.

Achieving all of those aims not only exhausts and demoralizes the opposition forwards, it can create more space outside as more would-be defenders are committed to the tight exchanges!

.jpg)

.jpg)