How the All Blacks dismantled the Wallaby lineout in Sydney

It’s a funny thing, momentum. One week, you’re playing for the Crusaders and winning the Super Rugby final against the Lions. Two weeks later, you’re an All Black and achieving a resounding success against Australia in the first round of The Rugby Championship in Sydney.

That was the case for red-and-black lineout forwards Sam Whitelock, Kieran Read and Scott Barrett, and they took something concrete with them from the success against Lions into the match at Stadium Australia.

As I wrote in my last article, the Crusaders’ victory was squarely based on winning the battle of lineout defence on the ground. In Sydney, they won the lineout battle in the air instead. The focus on lineout defence was alive and well in both games and there was a distinct carryover from the provincial tournament to the international competition.

One of the most stimulating training sessions on The Rugby Site is Victor Matfield’s superbly lucid series on the lineout. Matfield captained what is generally acknowledged to be the most dominant lineout in rugby history for the Springboks in the first decade of the new millennium.

South Africa always had five targets in the back five forwards, with Matfield and his second row partner Bakkies Botha supported by tall, athletic back-row forwards like Juan Smith, Danie Rossouw, Schalk Burger and Pierre Spies behind them.

The current New Zealand team is reaching towards that exalted level with its current lineout core group of number 8 Read, Whitelock and his second row cohort Brodie Retallick.

Matfield’s series helps illuminate the problems the Wallabies experienced in the first round. Victor begins his introduction by emphasizing the ultimate value of speed off the ground and into the air, of beating your opponent to the punch:

“Action always beats reaction. You have to have your footwork ready. If you want to beat a guy, beat him on the ground.”

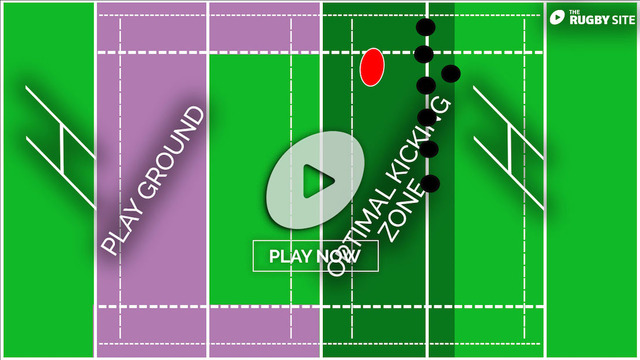

The failure of the Wallabies’ receivers was firstly a failure of footwork on the ground. Victor Matfield spends a large portion of time in the early part of his session on converting the footwork of his schoolboy charges from ‘two steps’ to ‘one step’. He suggests that taking out that extra step into your jump can buy you an invaluable extra fraction of a second to get into the air before your opponent:

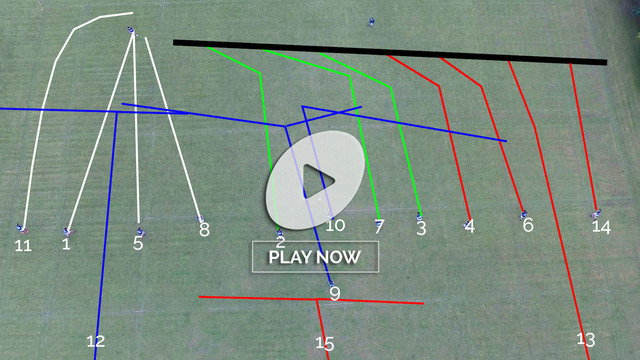

In the first example, the All Black defender opposite the intended receiver (Izack Rodda) is Brodie Retallick. He has turned to face Rodda and is looking for cues from Rodda’s body language about the timing of the jump.

The reason he is able to match Rodda’s rhythm and time his counter precisely is due to the fact that Rodda takes two steps to leave the ground rather than one. He is slow into the air and gains no advantage over Retallick off the ground.

The second example comes from the camera angle behind the posts. Retallick is again the main contestant, this time opposite the Wallaby open-side flanker Michael Hooper. With Hooper giving away over 20 centimetres in height to Retallick, it is essential that he beats Retallick on the ground in order to win the ball in the air.

The use of two steps towards the ball rather than one is even more obvious in this instance. It gives Retallick all the time he needs to get up and makes the most of his physical advantages in the contest.

Victor Matfield also comments on the importance of picking the right throw depending on how your opponent has set up:

Here Retallick is clearly set up looking down the line, and straight at the Wallaby hooker Tatafu Polota-Nau. He will therefore be reading the hooker’s ‘twitch’ first, not the movement of the receiver (Rodda again). This is the right moment for a change of position by either the receiver and/or his lifters before the ball is ever delivered, but that does not occur.

Polota-Nau throws the ball in, Retallick reacts and gets off the ground first – and for all the world it looks like an All Black throw rather than an Australian one!

One of the points Matfield emphasizes towards the end of his training session is the importance of making dummy or decoy motion convincing. If this motion does not attract a defender away from the intended target area, it is more than likely that the throw will be turned over again:

In this instance it is Rodda’s task to pull up the line and persuade Retallick that the real action is going to happen at the tail. In practice, big Brodie simply ignores Rodda’s movement and picks up Adam Coleman as he enters his zone of influence. Again the reaction is quicker than the action and the All Blacks beat their opponents on the ground to steal the ball in the air.

Summary

The Australian lineout disintegrated at Stadium Australia, losing seven out its 11 throws in from touch. If Victor Matfield was given the task of reviewing the Wallaby lineout performance on Saturday evening, he would not be a happy man!

Australia broke almost all of Victor’s cardinal rules for effective lineout performance. They took too many steps to get into the air and this allowed the All Black poachers to match rhythm with them; they did not pay enough attention to the set-up of the New Zealand contestants, and their dummy ploys were not effective in distracting them away from the real target area.

It was just about as complete a failure of a modern professional lineout as it’s possible to imagine, but credit is also due to the techniques and ability of the All Blacks who caused the breakdowns to occur. They took the momentum built from the Crusaders’ defensive lineout performance against the Lions and built it into a steamroller on the international stage.

.jpg)

.jpg)