How the Crusaders lineout defence stood up to be counted in Christchurch

Lineout defence is one of the most important single aspects of defence as a whole. On the one hand there are now far more set-pieces deriving from lineout than there are from scrum in the professional game (the ratio is approximately two or three to one); on the other the lineout presents some unique defensive problems which are not encountered anywhere else on a rugby field.

Since the law was changed to allow lifting of the receiver at the beginning of the professional era (Law 18 in the World Rugby law-book), clean catches have become the rule rather than the exception for the side throwing in the ball.

The greater certainty of a clean receipt has in turn increased the viability of driving the ball forward in the second stage of the attack. The unique selling point of the lineout drive is that it is the only situation on a rugby field where obstruction is legalized, with several players ahead of the ball-carrier once it can distributed to the man with his hand on the rudder at the back.

This has been a thorn in the side of teams from New Zealand for many years. The current All Black head coach Steve Hansen crystallized the objections after his side had conceded two lineout drive tries to Argentina in 2015:

“I’m not having a go against the ref, I’m having a go at the laws…It’s bloody boring – you can’t take it (the lineout drive) out of the game but you’ve got to make it a fair contest."

“You’re not allowed to have a back move where someone runs along the front of everybody and doesn’t let them tackle somebody, so have the same principles in a lineout."

“And the easiest way would be say you can collapse it. There’s never been anybody injured in a collapsed maul yet, but there’s thousands every week that get penalised. Just make that legal then it becomes half-pie a fair contest…”

“Having said all that, the laws are what they are and we have to be better at defending them. We got a nice reminder of that tonight.”

The primary test for the Crusaders in their Super Rugby final against the Lions was to confront this besetting issue head-on. South African rugby has always been based around the strength of its attacking play from the lineout drive – so stopping the drive (and the variations deriving from it) had to be top of the tactical shopping list for the men from Christchurch.

The Lions are expert at creating these situations, via the extraction of penalties from breakdown and scrum or through their own kicking game to the corners, where they can launch the drive in the opposition ‘red zone’ (inside the 22).

The challenge for the defensive side is to create a clear plan to force their opponents into channels where they feel they can be contained, or even turned over – to become the manipulator not the manipulated. In the event, the Lions failed to score a try from any of the four driving scenarios they created in the course of the first half, so the Crusaders definitely achieved their aim.

Let’s take a look at how the process unfolded.

The first Lions attacking lineout occurred on the Crusaders’ 22:

The first part of the Crusaders’ defensive plan is to create pressure in the mind of the Lions’ signal caller, number 5 Franco Mostert. To this end they threaten to compete on the opposition throw at lineouts deep in their own end.

Sam Whitelock is marking Mostert, and he is very active in defence – he makes three separate movements from front-on to side-on, and back again, before the ball is ever thrown in. He ensures that Mostert knows he is ‘reading’ him and tracking his movements closely.

The pressure is increased by the formation the Crusaders adopt. They are clearly set up to contest the throw, with two pods of three (one receiver and two lifters) set up in the front and middle of the line:

The window for Lions’ hooker Malcolm Marx to throw the ball into is no more than three metres wide between the two Crusaders’ jumpers, and unsurprisingly he makes an error in the ‘jaws’ of the pods on Whitelock and Kieran Read!

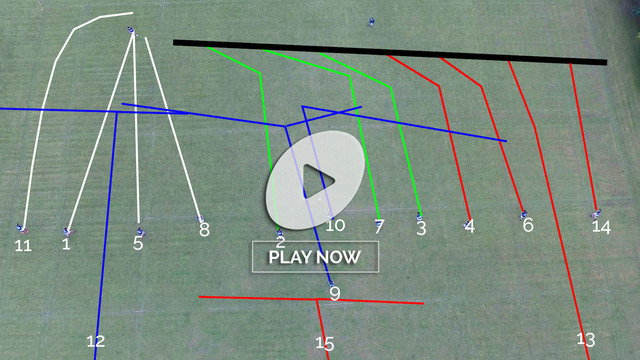

The Lions’ next attacking lineout opportunity arrived six minutes later:

Whitelock is once again very active in his movement opposite Mostert, and the pressure forces the Lions’ caller to take an ‘out’ – the easy option to the front rather than risking a longer throw.

The problem with launching a lineout drive off front ball is the proximity of the side-line. With touch only five or six metres away, the defence has more latitude to angle the counter-drive so as to force their opponents over the side-line.

This means loading up on the open-side corner of the maul as it starts to form. Whitelock gets a subtle first nudge in on the rear blocker (Mostert) to trigger momentum in the desired direction:

The impetus then continues with two other Crusaders forwards plugging in on low driving angles, forcing Mostert into a static, upright position:

There is nowhere for Mostert to go but upwards, and the ‘drive’ results in a predictable turnover a few moments later. The entire process was repeated almost word-for-word in the 27th minute.

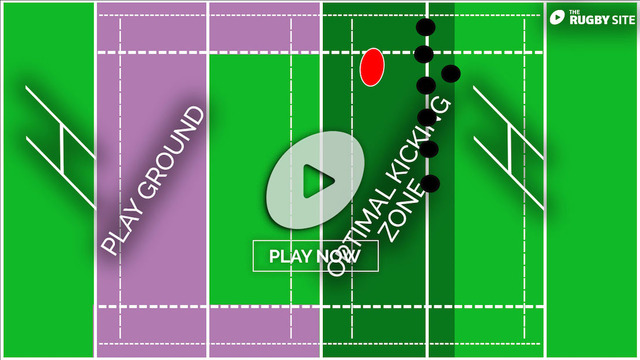

With their drive having been stuffed so comprehensively, the Lions varied by trying work moves off the drive as a decoy. The Crusaders were well-prepared for this option too:

Again pressure forces front ball, this time deflected to a second pod at the back on Warren Whiteley, apparently looking to drive the ball on in that area:

Because their fundamental threat to drive the ball straight ahead has already been defused, the Lions fail to convince the Crusader defenders to commit to the decoy. Only Read sticks his head into the three-man pod on Whiteley, with Matt Todd, Codie Taylor and Joe Moody still free to defend against the runner coming around the end of the line when the pass is made.

The lack of success on this play can be traced back to those first few footprints set down by Sam Whitelock at the 3rd minute lineout. Once Whitelock had established, with his first few steps, that he was going to be the aggressor on the Lions’ throw, it set in motion a disastrous domino effect:

- ’Reading’ pressure on the caller

- Front ball bail-out

- Clear target attacked – destroying the rear block

- No credible decoy options once the drive stalls

It was an object lesson indeed.

.jpg)

.jpg)