How to attack the short zones from restarts

In a recent article, I looked at ways in which the receiving side can use the idea of hang-time to their advantage. By holding the receiver up in the air for as long as possible, they maximize their chances of achieving a stable receipt, and exiting successfully from their own end.

The kicking team can of course also weaponize ‘hang-time’ at restarts, and that is associated with the amount of time the ball spends in the air from a kick-off or 22 drop-out.

The older version of kicking off to repossess the ball in the short zones (between the 40m and 22m lines) did not tend to emphasize the hang-time of the kick. Kicks were flat and low and designed for the chaser to meet the ball just before the defensive receiver as he crossed the 40m line.

The All Blacks were masters of this method in their World Cup winning years between 2011 and 2015. They would split Kieran Read to one side of the field and Brodie Retallick to the other, and tag them on to the end of fast, flat restarts by the likes of Dan Carter and Aaron Cruden.

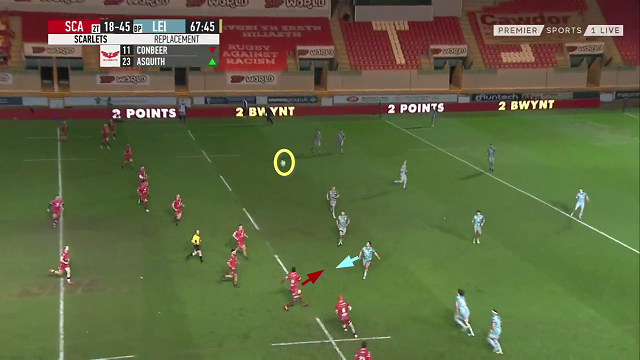

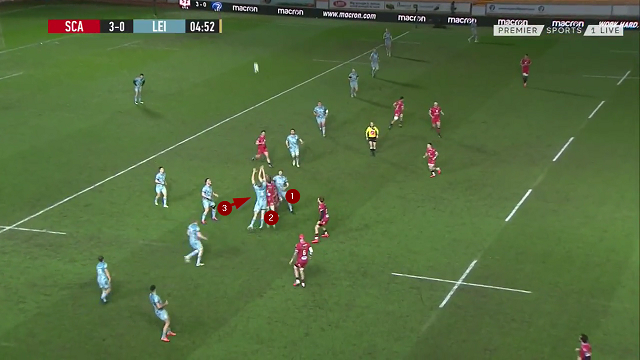

An updated example of this version occurred in the recent Guinness Pro 14 match between the Scarlets and Leinster. Scarlets used it to secure the ball from a kick-off when they were well behind on the scoreboard late in the game:

There is a race to the space just beyond the 40-metre line, between the chaser (Scarlets number 12) and defensive receiver. The idea is for the chaser to meet the kick at the moment he crosses the line, and therefore the essence of the play is timing:

In this instance the timing is good, and Scarlets get the ball back for the next phase of play.

The amount of time the ball spends in the air is necessarily low, at only 2.81 seconds from contact with the boot to the catch by the receiver.

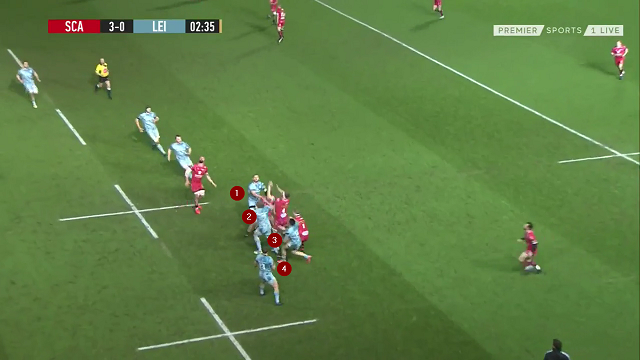

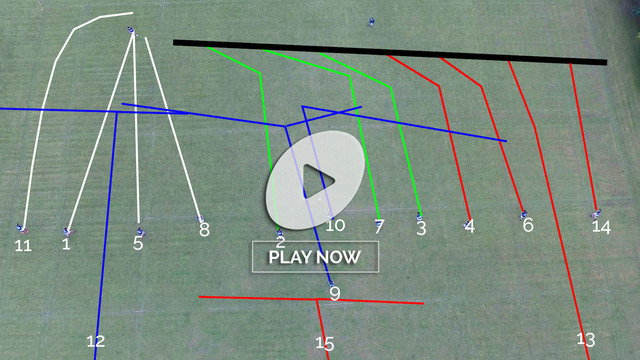

On their restarts, Leinster demonstrated a different interpretation – less dependent on timing the chase to the kick, and more on hanging the ball up for long enough to gather more bodies around the ball than the receiving team:

The kicker (Leinster’s number 10 Harry Byrne) cuts the ball up like a high pitching wedge in golf. His ’swing’ has a high, upright finish, in order to ensure that the ball descends as close to the vertical as possible.

That creates a hang-time of 4.52 seconds, slightly in excess of the recommended hang-time for punts in American Football (4.44 seconds). When the ball comes down from the clouds, the Leinster chasers outnumber the Scarlets around the ball by four players to three:

The hang-time on the kick enables the chasers to crowd the space around the defensive receiver and make a clean receipt highly unlikely – the outside chaser (Leinster number 14) actually has to curl back towards his own goal-line to close on the ball.

Once the clean catch is ruled out, numbers decide who will pick up the scraps and gain possession of the ball.

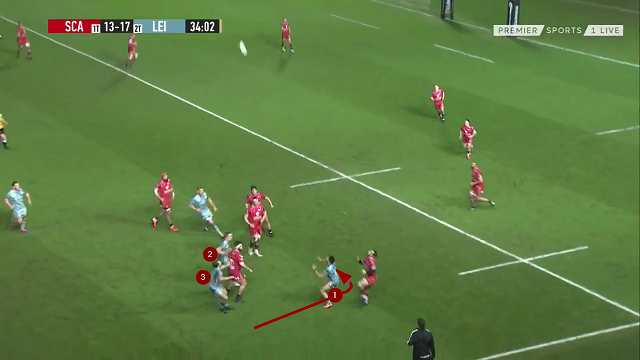

A second example reinforced the main idea even more strongly:

This kick-off travels further towards the 22m line than the previous example, but the 4.90 seconds of hang-time creates the same advantage in numbers around the ball (three chasers versus two defenders) and requires the outside chaser (Leinster number 14) to stop and curl back towards the ball:

From this shot it appears that it is the Leinster player who has been awaiting arrival of the kick, in position ‘A1’!

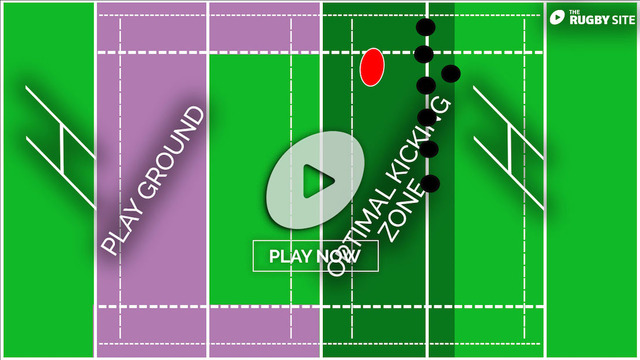

Leinster extended this policy to include their 22 drop-outs as well:

Harry Byrne again uses a high, ‘lean-back’ finish to create extreme height on the kick, so that the ball descends vertically. The ball only travels about 15 metres from kick to tap, but it takes 4.48 seconds to make the trip!

With a slight advantage in numbers around the landing zone, Leinster are well placed to pick up the deflection:

The older All Blacks method of targeting the short zones from restart demands more precision, and less room for error in the skill-set of both kicker and chaser. The kicker has to hit the space just beyond the 40m line, and time the kick to the chaser’s arrival. The chaser has to win a one-on-one ‘race to the space’, and catch the ball cleanly while travelling at speed.

The Leinster method is very robust and repeatable. The kicker has to be able to hang the ball up in the air for more than four and a half seconds, and achieve a vertical descent of the ball. But the chasers are not required to time their runs with particular accuracy, or catch the ball cleanly from the kick – they simply have to crowd the critical space and outnumber the defenders around the ball. If they can ‘hang around’ in the right area, they will get their reward!

.jpg)

.jpg)