How to beat a bigger team at lineout – part 2

Rugby is getting ever faster, at all levels of the game. By far the most significant reason for this is the dominance of the breakdown over the set-piece. In the amateur era, the ratio of scrums and lineouts to rucks was around 3: 1. In the professional game that has been turned on its head, with only one set-piece for every five or six rucks.

This has created more uniformity in shapes and sizes across the field, and it has also sharpened the demand for more speed in every position. This was a particularly influential factor in England’s semi-final win over New Zealand at the World Cup in Japan in 2019.

In the previous encounter between the two teams, at Twickenham in November 2018, Steve Hansen had made a crucial substitution with half an hour of the game to go. On came Scott Barrett to give the All Blacks four genuine lineout competitors, and the combination of Barrett, Sam Whitelock, Brodie Retallick and Kieran Read overwhelmed the England lineout in the last half hour of the match, winning six balls against the throw.

The substitution made such a strong impression on the All Blacks coaching staff that they started with Barrett at number 6 in the semi-final at Yokohama. England meanwhile selected only two recognised lineout players in the form of their second rows Courtney Lawes and Maro Itoje. They had two open-side flankers (Tom Curry and Sam Underhill at around six foot tall) alongside a non-jumping number 8 (Billy Vunipola) in the back-row.

The scene looked set for history to repeat itself, and for the England lineout to be taken apart. In the event, it only lost two of 20 throws, for a very respectable 90% win rate.

How did England achieve that result with what Eddie Jones jokingly called “two and quarter receivers”, against the four top operators picked by the All Blacks?

The answer to that question shows how important movement and timing are in the modern lineout. By using effective decoy motion and timing the throw to the moment when the opponent is least able to compete, any physical limitations can be overcome.

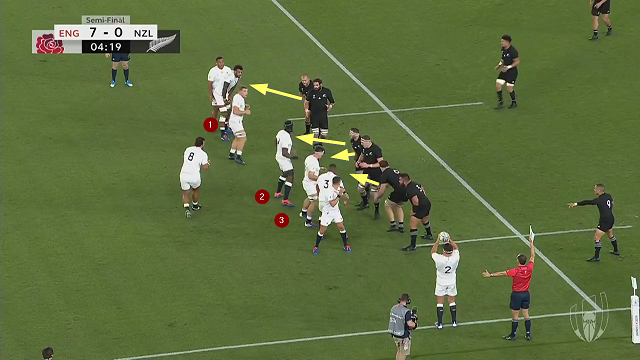

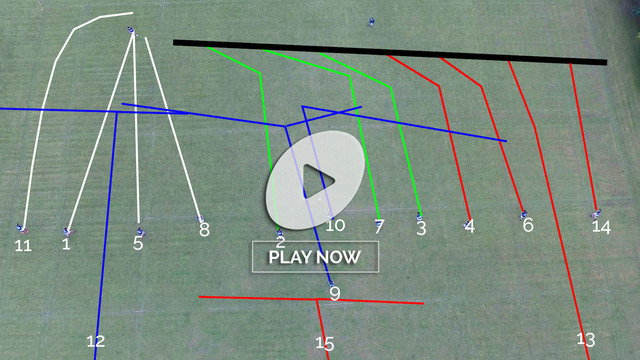

Here is one of the first lineouts of the game

The set-piece ends up with an uncontested win by Tom Curry at the front, even though he is initially opposed by no less than three of New Zealand’s biggest men – Read, Retallick and Barrett:

At this stage the All Blacks look to have all of the bases covered. Whitelock is observing Lawes at the tail, while Itoje and Curry are out-numbered by Read, Retallick and Barrett in the front and middle.

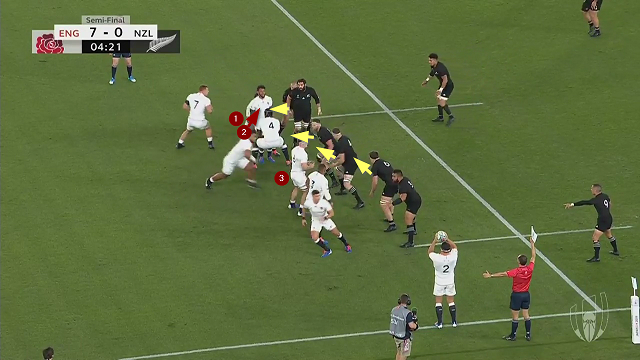

Run the situation on a few seconds, and the picture has changed dramatically:

The movement of the England caller Itoje to the tail to lift for Courtney Lawes, has hooked the attention of Read and Retallick and taken them out of the game and away from England’s real target, Tom Curry.

The gap between Retallick and Barrett has widened sufficiently that Brodie can no longer back-lift for Scott Barrett. Curry’s five inch height deficit doesn’t matter, because he has a coherent lifting unit around him, while Scott Barrett does not.

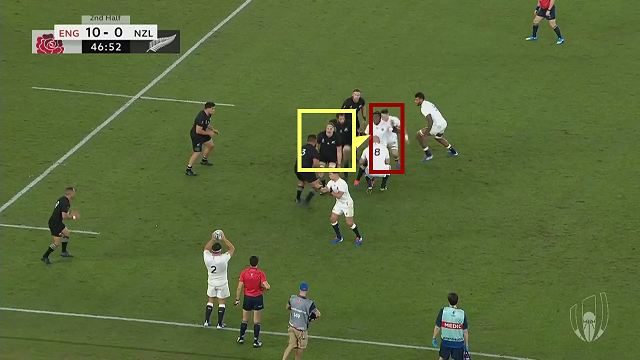

A second lineout just after the half-time break illustrated the same themes

At the start of the lineout, all of the New Zealand defensive focus is on the England lineout caller Maro Itoje as he moves down towards the centre of the lineout:

When he arrives in the predicted target zone, the All Blacks look well-prepared to launch their counter:

A lifting pod has formed around Brodie Retallick, with Sam Whitelock watching Itoje’s movement from the back and number 3 Nepo Laulala ready to stabilize Retallick from the front. Note how carefully the England prop Dan Cole (number 18) is nurturing the belief that Itoje will be the target receiver, getting into the kind of deep squat that tips off a lift for the man behind him.

In fact, Itoje is again the decoy with Curry unveiled as the true target a moment later:

When Itoje pulls out of the line, the New Zealand counter-jump is ‘blown’. The defensive pod, which was committed to Retallick. has no chance of recovering to mark Curry one spot further back in the line. The result is another uncontested win for a ‘small man’ who was not a recognised lineout expert before the game started.

The game as a whole was an object lesson in a contemporary truth which has replaced the old amateur assumption that you must start a match with four potential lineout targets in order to win your own ball. Two-and-a-quarter is quite enough, if you have the accurate movement and timing to make the fraction count!

.jpg)

.jpg)