How to beat a bigger team – lessons from the lineout

One of the major issues which can arise for rugby teams at all levels – but more especially for sides playing amateur football – is how to combat a differential in size and power.

That disparity in size and power is less likely to occur in professional rugby, where the standards of conditioning are far more uniform than they are in the amateur game. But it can still happen, particularly on occasions when the philosophies of the two protagonists are opposed, and different qualities in the same positions are valued.

Such a contrast in approaches to the game – and in selection practices – was very much in evidence in the recent Heineken Champions Cup clash between Exeter Chiefs and Glasgow Warriors.

The Chiefs pride themselves on using their power to create scoring opportunities. In recent years, they have constructed the most efficient red zone attack – in the last third of the field all the way up to the opposition goal-line – in the English Premiership, if not in the whole of Europe. Their conversion rate (from field position to tries) is very high in that zone.

Glasgow by way of contrast, pride themselves on their ability to attack with ball in hand from any position on the field, and tend to run far more phases than average out from their own 22 when looking for defensive weaknesses.

Those contrasting approaches are reflected in selection, and nowhere is this more apparent than in the back row. Exeter’s back row averaged 6 foot 3 and a half inches in height and 111 kilos in weight a fortnight ago, Glasgow’s was 6 foot 1 and 102 kilos. The Chiefs’ biggest man was number 6 Dave Ewers at 125-130 kilos, outweighing the Warriors captain Ryan Wilson playing the same position by at least 20 kilos.

The most searching test for a smaller pack of forwards in the modern game is probably not the set scrum, but is the defence of the drive from lineout. Where technical specialists at prop and hooker will always set up in the same spots in the scrum, at lineout the area of attack is more varied and smaller forwards are harder to protect.

Glasgow’s techniques for lineout defence, while playing the smaller hand, were of interest from beginning to end.

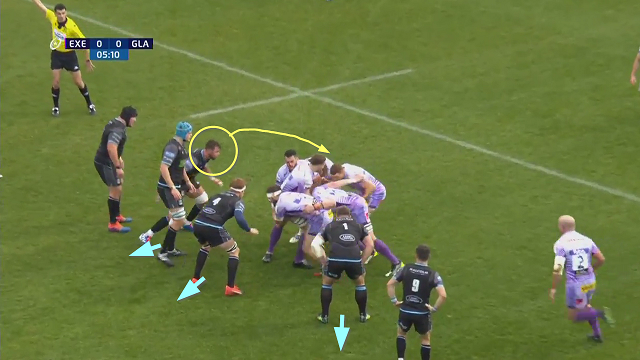

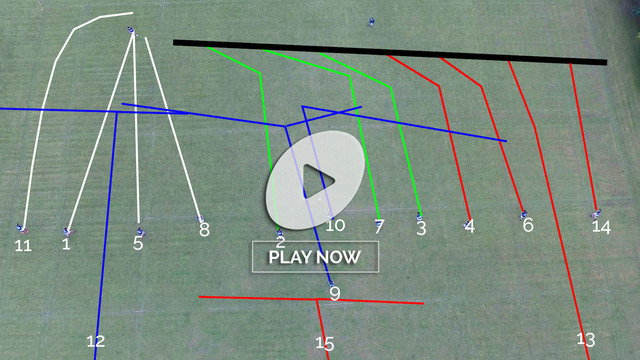

Their basic method was to avoid engagement with the Exeter maul as it began to form after the (uncontested) catch:

World Rugby’s offside laws require that a player “in front of a team-mate who is carrying the ball… must not interfere with play. This includes, preventing the opposition from playing as they wish” (Law 10.1.c).

In the above example, the three Glasgow forwards closest to the ball (numbers 1, 4 and 5 – in the blue hat) all take a step backwards after the catch is made. That means no maul has been formed because there is nobody in contact with the opposition, and therefore the ball itself remains the offside line. If any of the Exeter forwards ahead of the ball try to make contact from this position, they will be guilty of ‘preventing the opposition from playing as they wish’:

The one exception to Glasgow’s rule is number 6 Ryan Wilson, who is reading the situation from the side of the drive as it begins to form. As soon as he sees that the ball has been transferred to the back man (Exeter number 8 Sam Simmonds, entering from the half-back spot), he is free to swing around and make the sack.

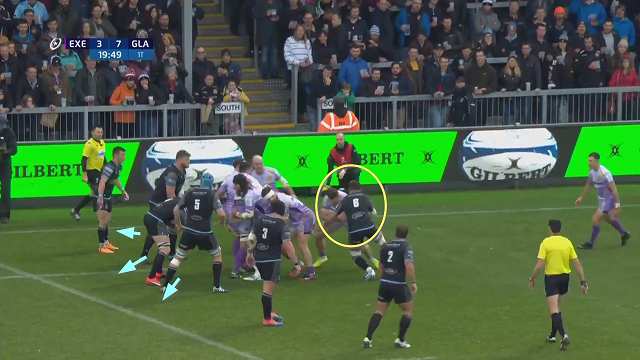

Glasgow were able to repeat the dose approximately 15 minutes later:

The defensive formula is identical: 1, 4 and 5 all drop back one step to avoid engagement, number 6 reads the play and swings around directly on to the ball-carrier as soon as he is clearly seen to be in possession of the ball:

By using this method, Glasgow were able to take away one of Exeter’s most dangerous attacking weapons without having to commit their forwards to the type of contest for which they least well-equipped.

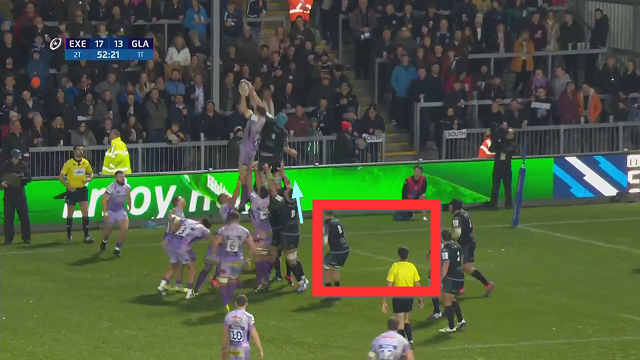

The other method which Glasgow utilized was competing for the ball in the air, rather than attempting to defend the drive on the ground, and in this scenario the Chiefs exacted a very convincing revenge:

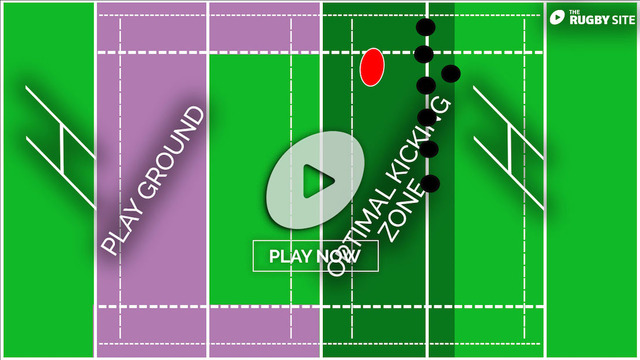

In this instance, three of the four key Glasgow forwards from the previous examples (number 4, 5 and 6) work together as a counter-jumping pod, with 4 and 6 lifting 5.

As soon as 6 supports the jump from the back, he burns his bridges and is of no further use in defending the drive:

A big hole develops directly behind Ryan Wilson, and it is here that the Chiefs establish a numerical advantage in the ensuing play:

Glasgow’s 4, 5 and 6 have all collapsed near the site of the original receipt, and there is nothing to stop the four remaining Chiefs’ forwards galloping all the way to the line, with the villain of the first two examples (Sam Simmonds) becoming the hero of the piece!

The value of novel methods of defusing a disadvantage in size and power need to be weighed carefully, especially in defence of the lineout drive. Go too far, make too many concessions in the interest of avoiding the physical contest, and it may create more problems than it resolves. Get it right, and you are freer to play the mobile game you want.

.jpg)

.jpg)