How to “cheat” effectively in maul defence!

Back in February 2017, Italy famously disrupted England’s attack by declining to commit any players to the ‘ruck’, which therefore became a tackle situation with no offside line in operation. Italian defenders loitered in England’s backfield, in the space between the halfback and first receiver throughout the game with success.

Five months later World Rugby introduced no less than six new law variations designed to create an offside line through the tackle as soon as an attacking player arrived in support. In the original iteration, that player did not even have to be in contact with an opponent. It was probably an over-reaction, but it also accurately reflected how law-making in Rugby Union is constantly trying to maintain pace with developments in a fast-moving professional game.

For the most part, it is struggling to keep up. For the most part, Rugby’s law-book is far too complicated and unwieldy, and the more clued-up teams can take advantage of the grey areas.

The area of the maul has now replaced the ruck as a case in point. If you take a look at Law 16, which deals with activity at the maul (typically beginning from lineout), there are 18 clauses and 14 sub-clauses to be satisfied by the players on both sides: View it here

The initial purpose of the maul is stated quite simply:

“The purpose of a maul is to allow players to compete for the ball, which is held off the ground…It consists of a ball-carrier and at least one player from each team, bound together and on their feet.”

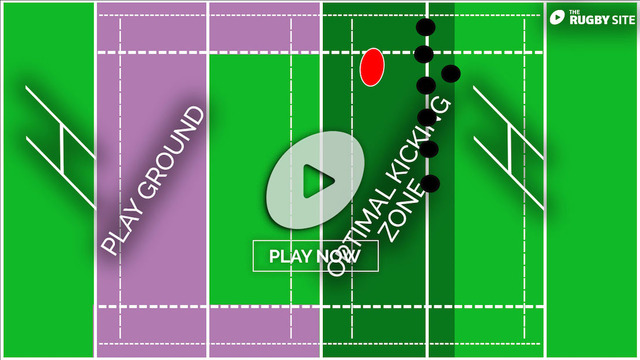

So far, so good. The problems begin with the definition of offside at the maul. Laws 16.4 and 16.5 indicate that:

“16.4 Each team has an offside line that runs parallel to the goal line through the maul participants’ hindmost foot that is nearest to that team’s goal line. If that foot is on or behind the goal line, the offside line for that team is the goal line."

“16.5 A player must either join a maul from an onside position or retire behind their offside line immediately.”

This sounds fine, but it does not take account of actions performed in the course of the maul itself, once the defensive players have bound on and the maul has been established.

Let’s take a look at a couple of recent examples of what can happen when a defensive team learns to take advantage of ‘a hole in the law’ at maul-time. They come from the European Champions Cup match between Benetton Treviso and Leinster.

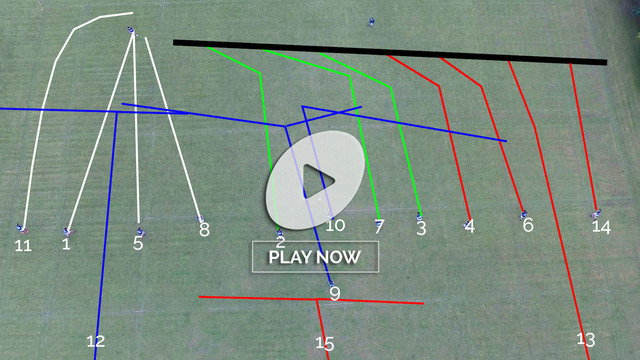

From two lineouts in the first half, Leinster attempted to drive the ball upfield by use of the maul. The first instance set the scene for the terms of the fight:

It is the activity of the Treviso number 4 that is primarily of interest. At the beginning of the maul he is bound into the centre of the maul, on to his opposite number Devin Toner:

As some momentum starts to develop, he is able to swing around the side, effectively blocking the path of release to the backs. He never loses contact with Toner and therefore is not required to retire behind the hindmost foot as the offside law demands.

He is attempting to block the connection between the Leinster ball-carrier and his scrum-half by throwing his right leg across into the space:

The Treviso player has done nothing to attract a penalty from the referee. He has maintained his original bind and therefore the offside rules do not apply. At the same time, he has taken a short cut around the side of the maul, and is able to influence the play negatively without having to use either notable skill or power to do so.

An even more flagrant example occurred later in the first half:

Here the Treviso number 7 has attached himself to the Leinster forward on the right-hand side of the maul. As the drive begins to make forward progress, he simply swings around the back of his man and steps in right behind the ball-carrier!

The offside line does not apply once the defensive player has committed to the maul, and a clever defensive side can use this wrinkle to their advantage:

The Leinster scrum-half is quite unable to get on to the ball as the Treviso number 7 interposes himself in the space between the ball-carrier and the number 9. It is legal but it is outside the spirit and intention of the law, and it does not require outstanding skill to achieve the desired result. It is certainly not conducive to positive rugby and creating ‘flow’ in the game.

On the other side of the coin, it shows how a smart defensive team can exploit holes in the law, and the refereeing protocols which support them, in order to take a short-cut to neutralizing an area of strength for the opposition. What Italy did to England in 2017 at the ruck was more spectacular, but in its own way what Treviso did to Leinster at the maul was just as meaningful, even if it was less obvious.

.jpg)

.jpg)