How to create breathing space for the lineout drive

In this article back in February, I looked at ways in which the receiving team at kick-offs will ‘hang’ the receiver in the air to deny an effective contest by the chasing side:

“Hang-time may be used as a more subtle weapon by the receiving team. They can exploit a current hotspot in the game’s law-making – the emphasis on policing illegal challenges to players already in the air – to their advantage. When they do it well, they can wholly reverse the momentum shift the kicking team would like to engineer from the restart.”

By holding the receiver in the air for as long as possible, the receiving team forces the kick-chase either to mistime the challenge, or back off from it entirely and allow an easy receipt.

The same principle was at work during the lineouts in the recent Rugby Championship match between Australia and the world champions South Africa, and it had a strong impact on the way the Wallabies were able to defend the Springbok’s signature lineout drive in the course of the match.

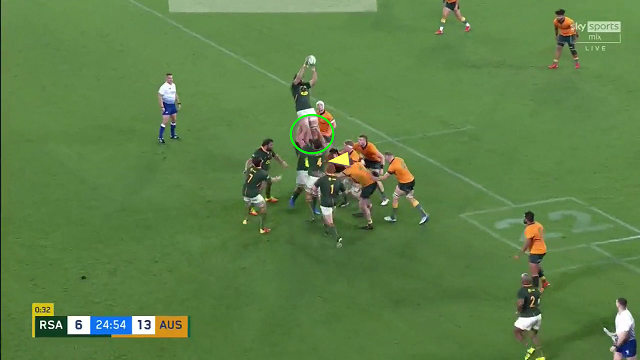

The first significant attempt at a catch-and drive by the Boks near the Australian red zone occurred in the 25th minute of the first half:

This lineout ended in a penalty to South Africa, with refereeing Luke Pearce picking out the Wallaby number 5 Matt Philip (in the white headband) for driving early on to the receiver, Lood de Jager.

The set-piece told the Springboks all they needed to know about how their opponents were going to defend the drive: they would use Philip to get into the space between the receiver and front lifter (Eben Etzebeth) early, to prevent the blocking wall from forming. Etzebeth is knocked out of the wall and the maul fragments.

South Africa’s response was immediate. In the first lineout, Etzebeth’s lift is well within the limits prescribed by law – on the thighs of the receiver, and with the arms nowhere near full extension at the apex of his jump:

18/19. Players in the lineout who are going to lift or support a team-mate jumping for the ball may pre-grip that team-mate, providing they do not grip below the shorts from behind or below the thighs from the front. Sanction: Free-kick.

As soon as the Springboks felt the way the wind was blowing, they changed tactics:

In this instance, de Jager is left hanging in the air for longer, inviting an early drive by Philip and a second penalty:

On this occasion, Etzebeth is fully extending his arms, and the lift only reaches as far as knee-height.

It is very smart play by South Africa in one of the grey areas of the law-making. The relevant law states that:

18/29. Once the lineout has commenced, any player in the lineout may:

3. Lift or support a team-mate. Players who do so must lower that player to the ground safely as soon as the ball is won by either team. Sanction: Free-kick.

Is Etzebeth lowering the receiver to the ground safely and immediately? How long does Philip have to wait before attacking the desired space?

The ripples sent out by these early lineouts had pronounced effects throughout a game in which Australia conceded three tries to close-range lineout drives. Matt Philip was dismissed on a yellow card for repeated maul offences in the 27th minute, and an identical situation repeated itself late on in the second period:

Once again, Philip is looking to attack the space between Etzebeth and the receiver (Franco Mostert) as early as possible, and once again South Africa draw the penalty:

Eben Etzebeth is at full extension, and his hands have come off Mostert’s legs before any contact is made. The extra ‘hang-time’ in the air forces a mistiming by the defence.

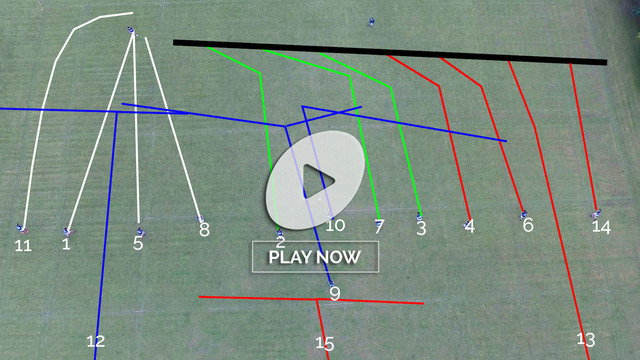

The same repeated outcome persuaded the Wallabies to adjust their defensive strategy at the next lineout, with Philip contesting in the air rather than competing on the ground:

With Philip spending crucial time off the deck, it gives the Springboks the scenario they want. Etzebeth at last has the opportunity to consolidate around the receiver and shut Philip out of the play:

The blocking wall is set, the second layer of the drive is in place, defenders are sealed away from a ball which is at the back of the drive with hooker Malcolm Marx. It is a perfect set-up which the Springboks duly converted into five points.

Summary

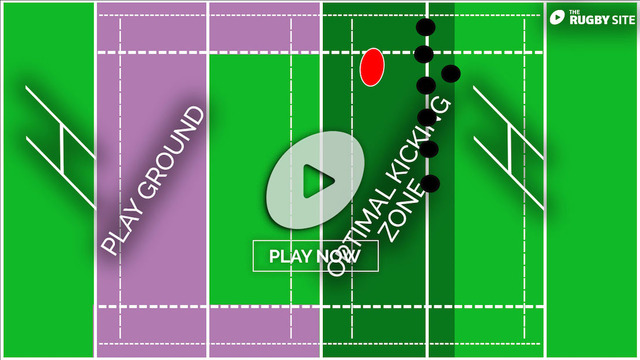

The value of hang-time in the air is a precious commodity, not just for the receiving team on high kicks or restarts, but for the throwing side at the lineout. If you can ‘hang’ your receiver in the air at full extension, it may offset the counter-drive by the defence and draw a penalty.

If they have to adjust their strategy, it gives time for the blocking wall to form, and you are in business. As in so many areas of the rugby lawbook, it all depends on the referee.

.jpg)

.jpg)