How to create breathing space on restarts

The concept of ‘hang-time’ is a relatively new one to professional rugby. It has long been employed by analysts in American Football to measure the amount of time the ball spends in the air off a punter’s boot. If the punter can ‘hang’ the ball in the air for four seconds+ while obtaining decent distance, it will give the chasers time to close on the receiver and cut him down quickly.

The idea readily translates to aspects of rugby like the box-kicking game, where the time the ball spends in the air enables chasers to pursue the kick more effectively.

‘Hang-time’ is also a key concept on restarts. In my previous article, the hang-time of kick-offs into the backfield allowed the chase to hurry the actions of the receiver, or block them entirely.

Hang-time may be used as a more subtle weapon by the receiving team. They can exploit a current hotspot in the game’s law-making – the emphasis on policing illegal challenges to players already in the air – to their advantage. When they do it well, they can wholly reverse the momentum shift the kicking team would like to engineer from the restart.

The penalties under Law 10.4 (i) are numerous and severe for a mistimed or misconceived challenge:

Penalty only – Fair challenge with wrong timing – No pulling down

Yellow card – Not a fair challenge, there is no contest and the player is pulled down landing on his back or side

Red card – It’s not a fair challenge with no contest, whilst being a reckless or deliberate foul play action and the player lands in a dangerous position

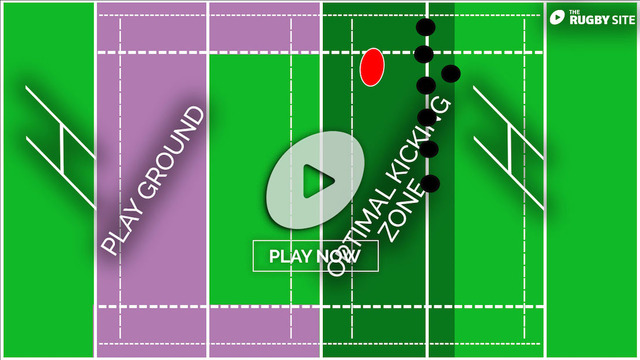

If you can get into the air early as a receiver and ‘hang’ there, you have the opportunity to set up a very productive exit situation.

Let’s look at some examples from the recent three-way series between New Zealand, Argentina and Australia:

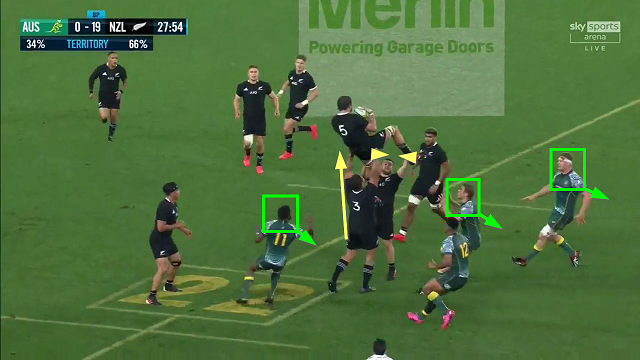

The key to the extra hang-time is accurate support by the receiver’s two lifters. The rear lifter (All Blacks #3 Ofa Tu’ungafasi) gets right in underneath the receiver’s back-side and achieves a full upward extension of the arms. The front lifter (Dane Coles) performs a balancing operation, ensuring that the receiver does not topple backwards over the rear boost. The result is that for a few moments, Sam Whitelock appears to be defying the laws of gravity!

But it is a circus act with a concrete aim. The longer Whitelock remains airborne, the more the impetus of the chase dissipates:

All three of the main Australian chasers have to back off from the challenge in the air and retire behind the ball, while #11 Marika Koroibete has to come back from an offside position. Whitelock is able to make a few cheap metres and set up a very comfortable exit on the following play.

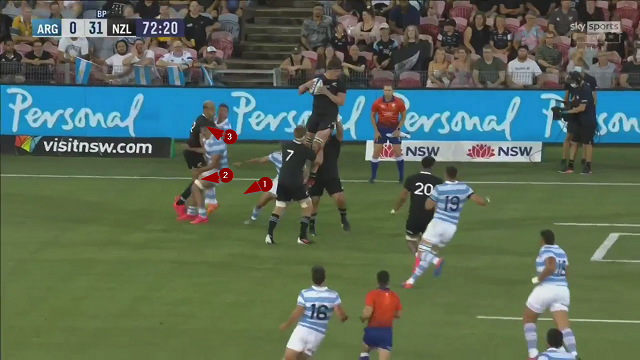

In this instance, the Pumas want to recover the ball from kick-off, but the stable extra time the receiver (Scott Barrett) spends in the air allows no less than three chasers to run past the ball. When Barrett looks in front of him, there is literally no defender standing in his path:

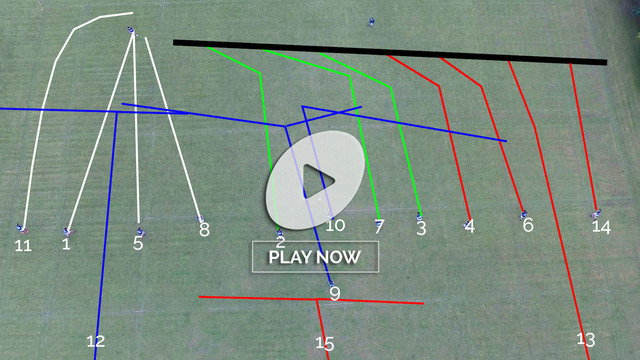

One logical development of the extra hang-time afforded to a short-zone receiver by his lifters is the use of the driving maul, to move the ball even further upfield on the exit:

Wallaby second row Matt Philip makes the receipt, and the Argentine chase backs off as the maul forms around him:

However, the Pumas captain (#6 Pablo Matera) engages briefly with Philip before dropping off, which means that a maul has been formed and the play should end in a penalty to Australia.

The concept of hang-time can be used as a weapon by the both the kicking and the receiving team on restarts. The kicking side can use the time the ball spends in the air to move the chase right on top of the receiver.

The receiving team can use the ‘untouchable’ status of the receiver to prolong the lift, and hence his/her time in the air beyond the 22m line. This can in turn set up an easy exit scenario, one in which all of the momentum on the chase has already passed the ball, and the return can even be ‘hidden’ within the comfort blanket of a driving maul.

.jpg)

.jpg)