How to cure the blight of scrum penalties in modern Rugby

One of the bêtes noires of the modern professional game of rugby remains the set scrummage. Despite the fact that there are far fewer scrums in the professional era than there were in amateur times, the production of usable attacking ball has dropped dramatically as the number of penalties awarded, mostly for technical offences, has increased.

Here are some basic stats from World Cups played in the two eras:

World Cups # of scrums per game (average) % of penalties awarded # of usable balls (average)

Amateur (1987-1995) 28 10.3% 25

Professional (2011-2019) 15 29.3% 10

In the first three World Cups, played before the game turned fully professional, there were twice as many scrums set as in the last three World Cups. The professional scrums resulted in three times the number of penalties awarded, and only ten pieces of usable ball – compared to 25 in the amateur era.

The main issue centres around the deliberate policy of scrumming for penalties by the side feeding the ball. That issue was fore-fronted on the highest profile stage, in the 2019 World Cup final between South Africa and England. The Springboks won five penalties on their own feed and that provided a major platform for a winning performance.

The majority of scrum penalties are won by feeding teams who manage to rotate up on one side of the scrum – typically on the open or loose-head side – and draw a technical offence out of the opponent – typically for ‘not pushing straight’. Law 19.19 states that “Players may push provided they do so straight and parallel to the ground.”

Let’s look at some examples which help explain why scrumming teams may look dominant, but only when they are feeding the ball. The following instances come from the recent European Champions Cup game between Exeter and Glasgow.

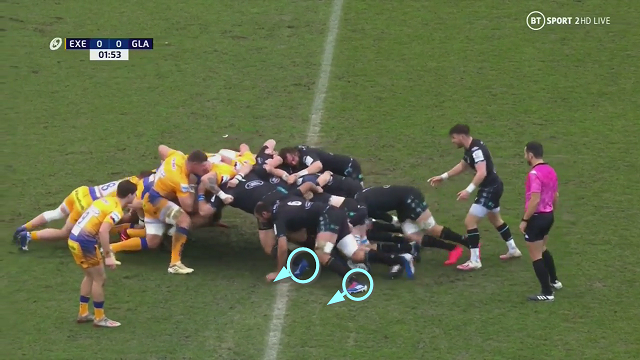

The first scrum of the game was awarded to Glasgow in the second minute:

Firstly, the referee should by law demand the ball be used at around 1:50 on the game clock, under rule 19.26 “When the scrum is stationary and the ball has been available at the back of the scrum for three-five seconds, the referee calls “use it”. The team must then play the ball out of the scrum immediately.”

He chooses instead to allow the scrum to continue for a total of 12 seconds – more than enough time for Glasgow to create an advantage on the loose-head side of their scrum.

The means by which the rotation is generated are subtle:

When the scrum starts to move, it does so out on the loose-head side. The Glasgow loose-head prop and the flanker behind him both take a step out to their left, so that their outside feet are well beyond those of their opposite numbers.

The effect is to increase the natural rotation of the set-piece, but it is generated by an optical illusion:

The Glasgow number 6, the left side second row and the number 8 are all pushing more or less straight down the field, but the loose-head prop in front of them has turned in on angle, so that he is facing towards the far touch-line.

The Exeter tight-head prop is penalized for not pushing straight, but in fact he is still in a pushing position at the end of the scrum – he has neither collapsed the scrum to the floor, nor has he stood up out of it.

Does he deserve to receive a penalty? A more proportionate reward might be to create more space for the attack on the promoted side of the scrum.

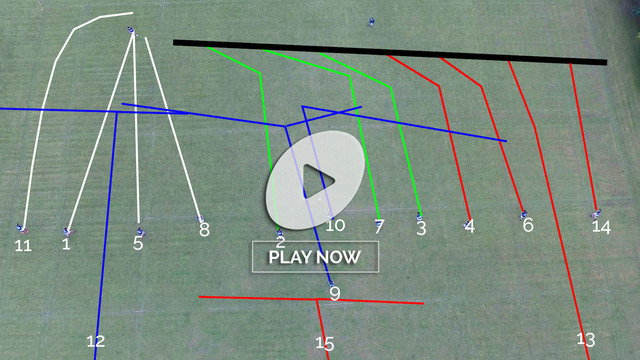

Currently the offside laws allow the defensive half-back to ignore rule 19.31: “All players not participating at the scrum remain at least five metres behind the hindmost foot of their team.” Instead of awarding a penalty, why not require the number 9 to retire the full five metres, and all forwards to remain fully bound for the duration of the set-piece? The dividend for Glasgow would then be their advantage in numbers on attacks to their left.

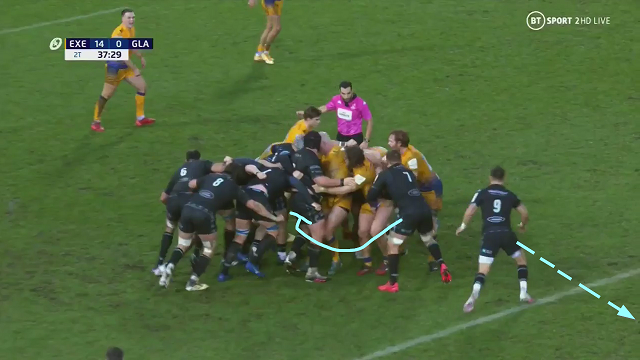

Exeter’s scrum on their own feed had both a similar look, and a very similar result:

Exeter are at least moving forward on both sides of the set-piece for a couple of seconds, helped by the referee’s laissez-faire attitude to rule 19.17: “Only when the scrum begins may the teams push.”

But ultimately, the picture is the same: the scrum rotates around the Exeter loose-head, the front row players stand up, and binds are broken on both sides:

Requiring the Glasgow number 7 to remain bound to his prop, and the defensive number 9 to retire to a new onside position with the rest of the backs, would grant an advantage proportionate to the picture of ‘dominance’ which has been presented to the referee.

Penalties are still necessary for dangerous play at scrum-time, like collapses under Law 19.37:

When a scrum is simply rotating around a corner to one side or another and the offence is technical, it is enough to reduce the punishment for the defence.

Require the forwards to respect their original binds, and the scrum-half to respect a new offside line five metres behind the set-piece. Then, the attacking side will enjoy an advantage in numbers, and space to the promoted side of the scrum. Whatever course World Rugby chooses to take in the future, let us hope it will render ball usage from the scrum a necessity, not an option.

.jpg)

.jpg)