How to get the ball away from the scrum quicksand

As in many other areas of life, there is a definite opportunity for Rugby to press the ‘Reset’ button now, and start again. The game is standing at a crossroads and must decide the best path forward for its further development.

Back in 2020, before the Covid-19 pandemic ever reared its head, World Rugby introduced a number of law amendments and variations designed to make both safer and quicker. Tackle height was to be lowered to avoid dangerous contact to the head, and the tackle area was to be cleaned up and reconstructed to produce quicker ball from the ruck.

The changes were hardly visible in the recent series between South Africa and the British & Irish Lions. There was an average of 54 kicks per game, and 35 minutes of stoppages in play in the second Test alone.

The scrummage became an attacking quicksand. In this article six months ago, I posted the statistic that 29% of the scrums in the last three World Cups (2011, 2015 and 2019) have been resolved by penalty awards.

The situation was even worse in the Lions series. 13 of the 39 scrums set (33%) were resolved by penalty, yielding an average of only nine total usable balls from scrum per game.

In the decisive third Test, with the series all square, six of the 12 scrums set ended in penalties, and there were 10 other resets. The paltry 26 minutes of ball-in-play time compared unfavourably with the 12 minutes and 25 seconds it took to set up all of those scrums in the first place. Neutral observers could be forgiven for wondering whether it was worth the effort.

The following sequence from the second half of the second Test in Cape Town summarized the issue neatly, but painfully:

A total of just over three minutes is spent resetting the set-piece after it rotates slowly away from the mark, and the sequence ends in a free-kick after all the huffing and puffing is over. It is an exercise in futility.

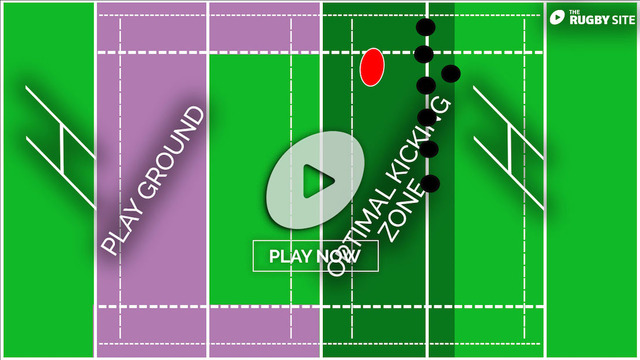

What is the best way to avoid the scrum penalty/reset quicksand, and create usable attacking ball? One route which the top international teams are beginning to explore more thoroughly is ‘channel one ball’.

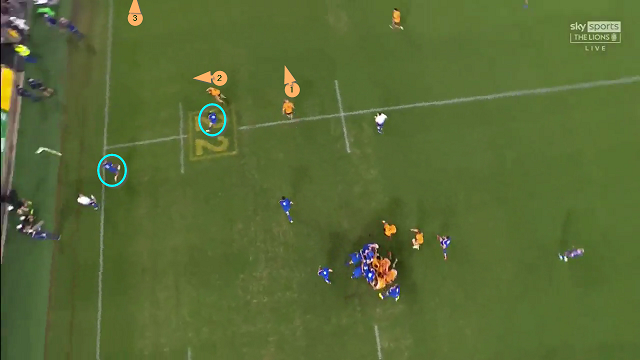

In the above sequence, with the Springbok forwards swinging around to the open-side of the field, the Lions have an opportunity to release the ball quickly in between the feet of the left flanker and number 8, and move the ball away to the short-side. That is ‘channel one’. Instead, they choose to move it to the number 8’s feet, the scrum-time extends, and events take their course.

In a similar scenario, France scored a ‘try from the end of the world’ in the third game of their summer series against Australia:

The ball emerges from the channel between the France number 6 and number 8 without either touching it, and it is in and out of the scrum in only one second. The impact on the Wallaby defence is profound:

With the Australian wing set deep to cover the possibility of a kick, France have created a simple short-side two-on-one, with their numbers 9 and 11 versus the Australian 9. The speed of delivery ensures that the Wallaby play-side flanker cannot release from the set-piece quickly enough to become a factor in the play.

It is worth showing the scoring conclusion of the play:

After the winger’s chip has been regathered successfully, there are men to burn on the right-hand side of the field.

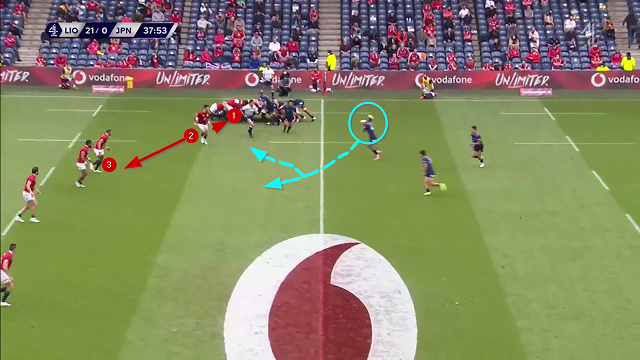

The modern masters of channel one ball are Japan. They do not want a prolonged contest at the scrum, and they do want to get their quick, skilful backs into play as often as possible. This instance comes from the Lions’ tour warm-up game at Murrayfield:

This scrum is set on the right, so channel one ball is on this occasion exploiting the wide side of the field. Again, the delivery of the ball is between the left flanker and number 8 and takes less than a second to reach the scrum-half’s hands.

The impact on defensive line spacings is just as profound as in the first example:

The Lions’ scrum-half finds himself trying to mark about 15 metres of space against the Japanese blind-side wing, and he is not going to get help from the play-side flanker, who is still nailed to the side of the scrum at the moment the pass reaches first receiver. The outcome is an easy clean break for Japan.

Scrums remain just as much of a bugbear post-Covid as they did before the pandemic, if the Lions series in South Africa is a reliable guide. In their current form, they waste valuable playing time through resets, and one in every three scrums is resolved by penalty – which means the next attack will be launched from lineout instead.

Summary

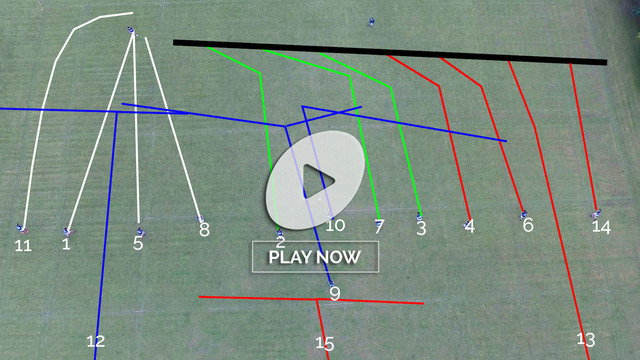

Channel One ball is re-emerging as a way to clear the ball from scrum more swiftly, and initiate attacks with the defensive back-row still pinned to the set-piece. The chances of isolating the defensive 9 on first phase are good, and there is a potential advantage to the open-side on the next phase with opposing forwards later to wrap. It is one way to make the game quicker and more constructive, and apply the intent behind World Rugby’s law amendments back in 2020.

.jpg)

.jpg)