How to mix backs and forwards at the set-piece!

There are a number of occasions on a modern rugby field when the roles of backs and forwards – always so discreet in the amateur era – either become blurred, or markedly overlap.

There are likewise, a number of positions where that overlap is more likely to occur, most notably between the inside backs and loose forwards, who are often built along similar lines in the professional game.

Number 12’s like Ma’a Nonu at 108 kilos and Brad Barritt at 103 kilos, could easily have translated to wing forward in previous times. Rugby League forwards like Sonny Bill Williams, Andy Farrell and Sam Burgess have all found a home at inside centre in the sister code.

Having inside backs of such dimensions can turbo-charge key elements of your attack and defence alike, and not just via their ability carry ball, compete for the ball on the ground, or clean out with power. Even at set-piece situations, they can add value.

In two recent games, one from each hemisphere, inside backs were used successfully to empower driving mauls from lineout. They were not there just there to supervise activities or encourage their forward brethren either, they made a critical contribution to the success of the attack!

It is not simply a matter of adding weight and extra bodies to the drive, the backs concerned have to know what they are doing and the technical reasons why they are in that position.

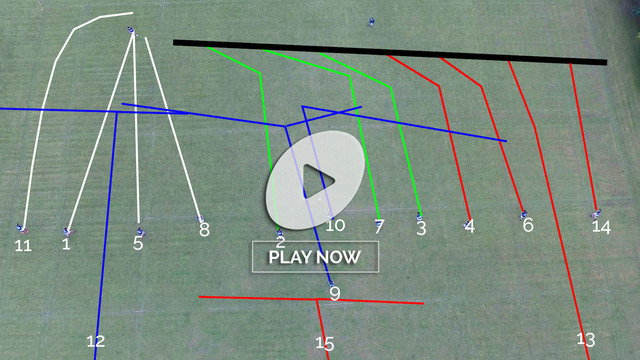

The first example comes from last weekend’s Super Rugby game between the Brumbies and the Blues.

The drive continues for a total of 20 seconds, so we will begin by dividing the footage into two digestible halves:

This first segment lasts from the inception of the drive to the point where the first back (Brumbies’ number 10 Christian Lealiifano) joins the maul.

At the start, after the ball is pulled down out of the air by receiver Sam Carter, it is strictly ‘forwards only’. When the Blues commit their sixth forward to defence, it appears that momentum has stalled and the referee will ask the Brumbies halfback to move the ball out:

This screenshot illustrates the problem facing the Brumbies. There are six Blues forwards in and around the drive, even though two – Akira Ioane and Patrick Tuipolutu – have become temporarily disengaged from it.

If the Brumbies allow Ioane and Tiupolutu (two of the Blues’ biggest men) to rejoin, the drive will be going nowhere.

At the same time, the reasons why momentum has ground to a halt are quite clear. There are no more than two offensive ‘layers’ built into the maul, and the formation is only two metres long from head to tail.

This means that the defenders are that much closer to the ball, and more likely to be able get their arms through and cause disruption.

It is at this point that two of the Brumbies’ inside backs – Lealiifano and 105 kilo inside centre Irae Simone – pick their moment to join the maul:

The first consequence of their entry is that the ball-carrier, hooker Folau Fainga’a, is able to drift back further from potential disruption, with both Simone and Lealiifano making contact (as the law requires) before pushing ahead to create a new layer of depth to the drive.

At the next critical juncture, the maul has extended to four layers instead of two, and is now closer to five metres long:

From this position the drive is unstoppable by legal means for the defensive side. They cannot penetrate through on to the ball-carrier and their opponents all have lower body positions. As legendary NFL coach Vince Lombardi always used to say in such situations, ‘the low man wins’.

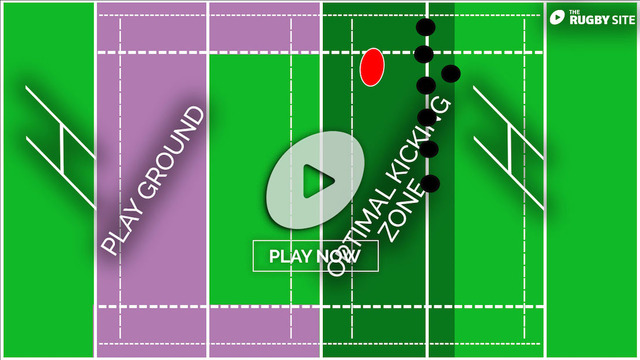

Now let’s look at comparable drive, in a comparable competition in the Northern Hemisphere, the European Champions Cup. The example comes from the pool stage match between Saracens and Glasgow Warriors:

As in the scenario from the Super Rugby game, the drive does not start with a huge amount of promise. Once again, the maul is very shallow, and more importantly it appears that it can only move forward on one side:

The issue is circled – the Glasgow defender is lower than his opponent in the battle of shoulder height and has an advantage on the open-side of the maul. This important factor is forcing attacking momentum remorselessly towards touch.

It is at this moment that Brad Barritt enters the fray, not just to add a body, but to add power at the right point of contact:

The Saracens centre has identified the area where he needs to insert himself in order for the drive to be successful, and the following screenshot demonstrates just what an effective intervention he makes:

Suddenly the Glasgow open-side defender is on the receiving end of the body height equation, and that enables Saracens to go forward on Barritt’s side – even though it is ‘inside centre versus tight-head prop’. In the professional game, it does not matter if your technique is sound.

Backs can help the forwards in the tasks that used to belong solely to the pack – but only if they understand what their roles are and how best to apply their power. That overlapping understanding is as much as anything, a sign of the changing times in Rugby.

.jpg)

.jpg)