If you want to build an attack from set-piece, then the lineout is the best platform from which to do it. Consider the following stats: the number of scrums has dwindled from an average of 32 per game at the inaugural World Cup in 1987, to 14 at the most recent tournament in 2019, and 30% of those ended in a penalty.

Although the number of lineouts has also taken a cut – from an average of 45 per game in 1987 to 25 in 2019 – the overall reduction is not as significant.

Moreover, in the intervening 35 years ball security has improved immensely: the 68% own-ball retention rate at the first World Cup had risen to 91% by 2019. So, for the attack, the lineout it is.

A well-managed lineout will expect to win between 85-90% of its feed, and modern lineout defence in the air has become increasingly creative in response. As always, there is an opportunity to exploit the considerable grey areas of the law to your advantage. Here are the two rules governing the set-up of the lineout:

18.10. Each team forms a single line parallel to and half a metre from the mark of touch on their side of the lineout between the five-metre and 15-metre lines. The gap between the lines must be maintained until the ball is thrown in. Sanction: Free-kick.

18.21. Players must not make any contact with an opponent before the ball is thrown in. Sanction: Penalty.

In the hurly-burly of a real game, the referee will often neglect to maintain the required gap all the way through the lineout process; furthermore, he may also allow a reasonable amount of contact between players in the air, in the interest of supporting Rugby’s primary directive that the ball must always be contestable by both sides.

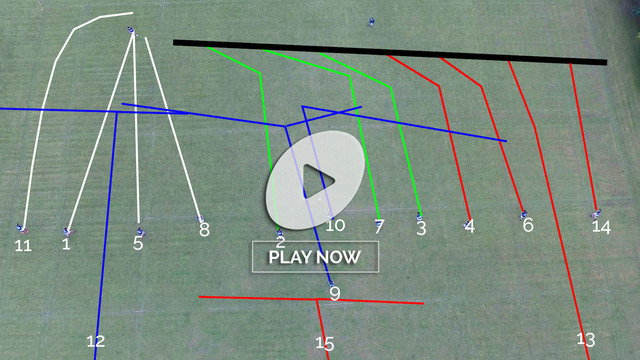

There is an opportunity presented to an intelligent and well-led defensive lineout, and it was exploited in a high-profile game between England and Wales in the Six Nations at the beginning of the year. England’s only try of the game came from a Wales lineout in which England had successfully compressed the space between the two lines of players:

In between the initial set-up and the beginning of Welsh movement up and down the line, England take a couple of shuffle steps across the line so that they are standing directly under the flightpath of the ball. There is no gap at all as the ball comes in from touch:

There are severe technical problems which the Welsh lineout is unable to solve in the amount of space available. England’s Maro Itoje is shoulder-to-shoulder with the intended receiver (Adam Beard), and even more significantly, the inside foot of Itoje’s front lifter (Charlie Ewels) is already overlapping that of the man opposite (Wyn Jones). Beard cannot get off the ground comfortably and he cannot receive any support from his front boost. The ball sails over the top of Beard and into the grateful hands of England back-rower Alex Dombrandt.

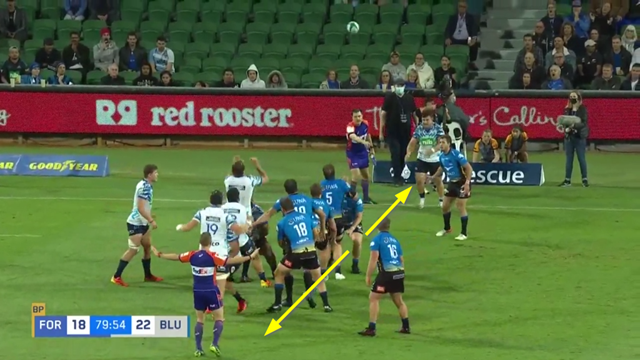

The Blues’ lineout suffered from a similar sense of claustrophobia in their recent Super Rugby Pacific encounter with the Western Force. The Force lineout was led by the Wallaby lineout captain Izack Rodda, and he forced the Blues to give up no less than five lineout turnovers in the second half of the game:

Many attacking teams like to use the on-trend ‘walk-in’ lineout, in which the both the formation and numbers are disguised from the opponent until the last possible moment. The negative aspect is that an unformed line allows the defence to creep forward and close the gap. Thus, Rodda is already across the line and underneath the delivery before Luke Romano for the Blues.

The key for the defence is to start with the one-metre gap at set-up, then use short shuffle steps to creep across the line in the interval before the throw:

In this case, Rodda is directly under the flightpath of the ball – not interfering directly with the receiver (Akira Ioane), but nonetheless making light contact in the air. The defender must get his outside arm in between, and slightly ahead of the two arms of the intended receiver to either prevent a clean catch, or make a clean steal.

The other positive spin-off for the defence is that successful ‘creepage’ can ruin the timing and co-ordination of the throw – the Blues surrendered the turnover via two Not Straight calls in the second period:

In this instance, the unified Force shuffle forces the Blues receiving unit to back away from the original line of touch, compelling the hooker (Ricky Riccitelli) to follow them with his throw towards the Blues goal-line.

Summary

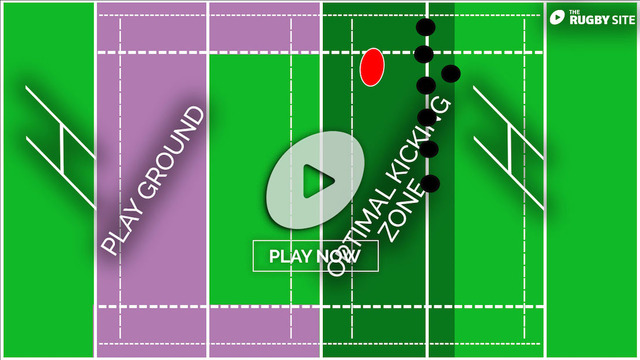

Lineout defence is becoming ever more important in the modern game, as the lineout becomes the by far the major weapon of choice for set-piece attack.

It can begin before the ball ever enters the field of play – by pressurizing the space between the two lines, and especially when the throwing team delays formation by walking in late. If your receiver can get below the flightpath of the ball, bisect the arms of the intended receiver, and the lifting pod can engineer that overlap on the ground, the defence will be in business.

.jpg)

.jpg)