Sir Dave Brailsford has had a huge impact on British Cycling. It was he who first developed Team Sky into the juggernaut force in the Tour de France that it is today, and whose vision helped convince riders like Bradley Wiggins and Chris Froome that a British citizen could win the event; it was he who (as Performance Director of British Cycling) instigated the revolution in attitude which has resulted in 16 cycling gold medals in the last two Olympic Games.

Brailsford believes in the “aggregation of marginal gains… the 1% margin for improvement in everything you do.” Put all those little micro-wins together, and one day you will see an almighty change in the world outside them.

Marginal gains didn’t mean just the obvious adjustments, like tweaking a rider’s training schedule or nutritional program – it meant the barely-visible parts of the environment surrounding the sporting performer.

Brailsford examined all the assumptions involved in team preparation – what colour should the floor of the maintenance truck be painted to best show up the dust and dirt that could compromise the repair of bicycle mechanisms? What was the best design of the team bus for a rider’s rest and recuperation? What was the best type of massage gel to relax the performer’s body?

Success is defined by ‘winning’ in the (seemingly insignificant) small details rather than aiming for big results. The mastery of small, repeatable habits is more important than achieving outcomes.

It is easy to see the aggregation of marginal gains at the heart of the scrum thinking taught by Jase Ryan and Owen Franks in their coaching modules. The emphasis on minimal foot movements, stepping forward and then ‘catching up’, short rather than long lateral movements, and minimal uplift of the chest and core area away from the ground, are all textbook Brailsford – but set in another theatre of operations.

The changes in the scrum engagement laws have had a pronounced impact. There is no more ‘big win’ at the hit as Ryan indicates, but a series of small and unnoticeable adjustments, wrestling style, which can bring advantage to the side which practises them at and just after, the command ‘set’.

It is no accident that it is the Crusaders scrum, now coached by Jase Ryan, which has grown five of the top six current All Black front-rowers (Joe Moody, Wyatt Crockett, Codie Taylor, Owen Franks and Nepo Laulala). That academy teaches the mastery of repeatable habits, and the importance of making small but significant adjustments.

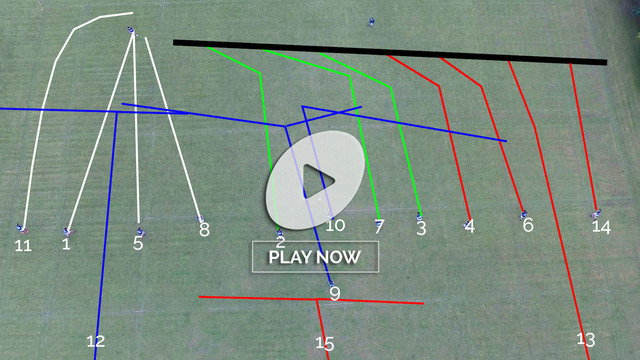

Let’s take a look at the first scrum of the game from the second Bledisloe Cup match between New Zealand and Australia in Dunedin to illustrate the point about small gains adding up. It occurred in the 5th minute of the game:

Australia started with a young and relatively inexperienced tight-head prop in Allan Alaalatoa, and 31-cap Joe Moody went to work on him.

At the command ‘set’ both forward units are linear and pushing in the same plane:

Joe Moody manages to insert a small step forward with his left or outside foot, forcing Alaalatoa to take one step backwards with his right, in between ‘set’ and the feed. He keeps his core low and flat to the ground. This small gain may not seem to mean much in isolation, but it changes the configuration of the scrum significantly before the ball is put in:

Allalatoa’s body is now a little over-extended, and the change in the position of his right foot has had a couple of significant if unnoticeable effects. His hips are now above the level of his shoulders, and that it turn has had an impact on the two men pushing behind him.

The top of the head of his second row (Rob Simmons) is now visible, which means that Simmons has slipped above his ideal position and is pushing upwards rather than straight behind Alaalatoa’s left buttock. Meanwhile Ned Hanigan has also lost shape on Alaalatoa’s right hip, and is now applying force downwards – so that neither of his main supports can ‘power up’ fully on the Wallaby tight-head. Meanwhile the All Blacks are still pushing in the same strong, flat plane as in the earlier frame.

The situation is far more fragile than it appears for the Wallabies, but that only becomes evident only after the ball is fed into the scrum by Will Genia:

The pushing angles of both Simmons and Hanigan have become more exaggerated, to the point where they can no longer offer any support at all to Alaalatoa. A couple of moments later Ned Hanigan shears off the scrum completely and fall into the tunnel as the All Blacks complete the turnover!

Joe Moody’s small gains at the beginning of the scrum have had a very big impact, with New Zealand achieving an ideal turnover attack scenario within the Australian 22.

Summary

Back in the amateur days of Rugby Union, when hookers were actually required to strike for the ball, a good number two knew that even a push of six inches to a foot against him would be enough to destroy the co-ordination of his scrum.

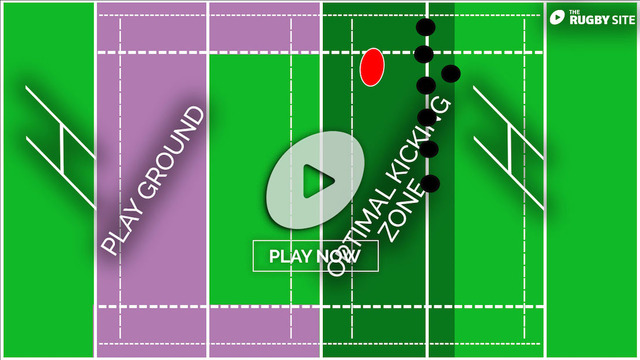

Those days are coming around again, with the new experimental scrumming laws forcing the hooker to raise his foot and strike for the ball rather than try to keep his feet back and drive over it.

The changes in the engagement process over the past two seasons have also depowered the ‘hit’ and forced front row players to look for marginal gains in the space between ‘set’ and the feed – a step forward and catch-up, a small lateral movement or flex of the upper body to upset the opponent.

The domino effects of a small gain in the front row can be catastrophic for the co-ordination of the opposition scrum as a whole. Get the detail wrong and the entire structure will be threatened by collapse! Then you will see the real value in the gospel that a Jase Ryan, or an Owen Franks preaches.

.jpg)

.jpg)