Start the game as you mean to go on. The impetus built off an accurate kick-off can be truly startling. Over six years ago I wrote the following article on The Rugby Site https://www.therugbysite.com/blog/set-piece/the-importance-of-restarts , based around the game between Samoa and Scotland at the 2015 World Cup.

In that article I observed how quickly momentum can change in those vital moments after you have just made a score yourself:

“Kick-offs can be one of the most direct ways of changing the momentum of the game. Your opponent has just scored, and you have the opportunity to exploit the momentary relaxation or ‘mental pause’ that tends to occur when that happens.”

In the Samoa-Scotland match, Samoa profited from their ability to repossess short kick-offs targeted just beyond the Scotland 40m line, and scored three of their first four tries directly from those scenarios, or from pressured exits derived from them.

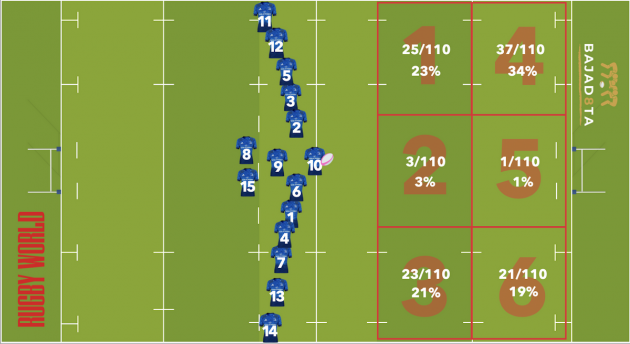

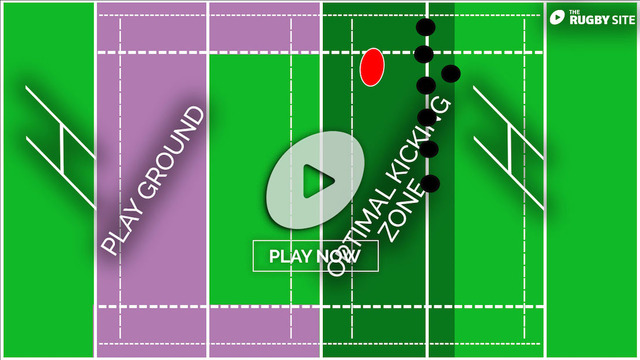

The vast majority of kick-offs are targeted diagonally towards the space around the receiving team’s 22m line, or beyond it. In an excellent basic guide for Rugby World magazine https://www.rugbyworld.com/takingpart/rugby-explained-kick-offs-120112, analyst Geraint Davies produced the following stats for restarts based on the 2020-2021 Guinness Pro 14 season:

96% of restarts tended to be directed to the corners (zones 1,3,4 and 6), with a mere 4% down the middle of the field (zones 2 and 3). Those figures reflect the reality that kick-offs straight ‘down the pipe’ tend to be criminally undervalued, and hence under-used.

What are the main benefits of restarting up the middle?

Potential kickers are much further from the safety of touch, which means more passes need to be made, and more phases built in order to play out of the exit zone.

The defensive lifting combinations (one receiver plus one booster) also tend to be less cohesive than they are on the corners, where they can expect to see a lot more of the ball.

Any reclaims by the kicking team automatically spot them in the middle of the field, with the option to attack on either side of the first ruck

The recent third round Rugby Championship game between Australia and South Africa featured an unusually high ratio of kick-offs up the middle, with five in total (three by the Wallabies and two by South Africa), and the outcomes falling out heavily in favour of the kicking team.

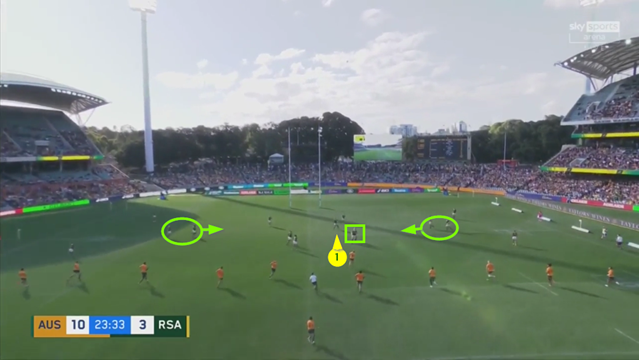

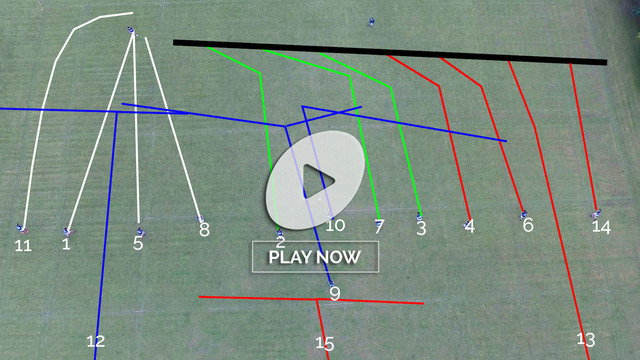

First, let’s look at the basic defensive set-up which makes the kick up the middle so inviting:

This is Australia’s second kick-off of the game, with their athletic 6’4 full-back Reece Hodge chasing on to the Springbok middle pod. The outcome showed what can happen when the ball descends on lifting/jumping combination that is less cohesive than the two second row-based pods used to protect the edges:

The Springbok middle pod (Pieter-Steph Du Toit receiving and Malcolm Marx lifting) get their timing comprehensively wrong, to the point where the ball sails over Du Toit’s head and he is left suspended, upside down in the grasp of his hooker. Reece Hodge duly won first touch.

Hodge had also won first touch at the opening kick-off on exactly the same play, leading to the opening Wallaby try in only the second minute of the game:

The defence is even thinner in the middle on the first attempt, with Du Toit having no booster behind him at all. That is lack of cohesion in a nutshell. Hodge’s first touch also granted Australia an attractive attacking position with the two Springbok centres split to either side of the field:

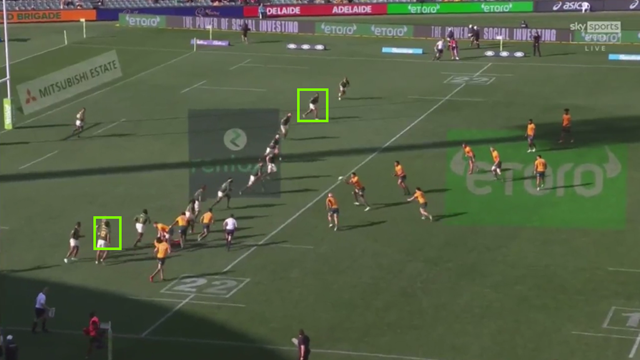

Much later in the game, Hodge cleverly attracted a penalty for sealing-off at the breakdown with the Boks clearly feeling the strain to win the ball back in this area of the field:

It is the 76th minute of the match, and the middle of field is still relatively weakly defended, with the cleanout forwards uncertain of where the receiver will go to ground.

It was also surprising that South Africa gave up on the same tactic when it had proved successful:

The safety of touch is probably out of reach after Hodge sets the first ruck, so the Wallabies have to build two rucks and make three more passes to get out of their own 22, even with the bonus of a tackle bust by Len Ikitau on the second phase. At the end of the day the exit kick is brought all the way back to the Australian 40m line in the middle of the paddock, and that represents a small win for the Springboks.

Summary

The kick-off straight up the middle is an underused tactic which presents the receiving team with some definite problems to solve. Should they move a more experienced two-man pod infield to receive the kick, or bring their full-back forward? How do they work their way out towards the side-line in order to find the safety of touch? How do they defend if the kicking team wins the ball back in the middle of the park? They are all valid questions which could be asked a great deal more often than they are.

.jpg)

.jpg)