On attack, one of the perennial issues for coaches is picking the best platform for attack. The great All Blacks’ sides of that golden decade between 2008 and 2018 prided themselves on counter-attack off kicks or turnover ball, but in recent times it has become obvious that the lineout provides the most stable medium.

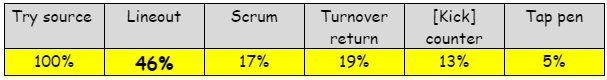

Here is a table of the tries scored at the 2023 Men’s World Cup, split out by origin:

That is a typical distribution which forefronts the attacking lineout as the basis for almost half of all the tries scored in professional rugby. Within that distribution, 31% were scored within phases 1-4, still far more than any of the other individual scoring platforms.

There tend to be more variables contained in other starter plays: tapped penalties are relatively rare birds, scrums as often as not end up in penalty awards, the player dynamics present on turnover and kick returns are harder to predict. The message is clear: emphasize lineout as your principal ‘structured’ attacking platform, and aim to score quickly from it.

With the attacking lineout complex, the proportion of tries scored from the threat of the driving maul, as opposed to off-the-top lineout is growing. There is a huge amount of variation and flexibility available within plays which begin as a driving lineout. First phase kicks off with the threat of the drive concentrating five or six defending forwards around the ball, without the companion risk of penalty that exists at the scrum.

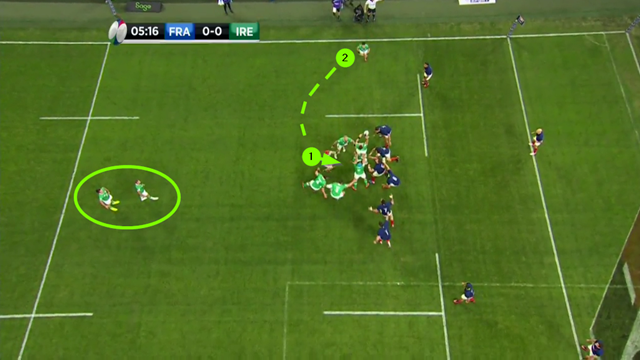

In the recent first round match between Ireland and France at the 2024 Six Nations, the current Six Nations champions from the Emerald Isle provided some seminal illustrations of the attacking potential contained within plays which begin as driving lineouts. They also showed how well forwards and backs can mesh and interact in these situations, even very early in the phase count.

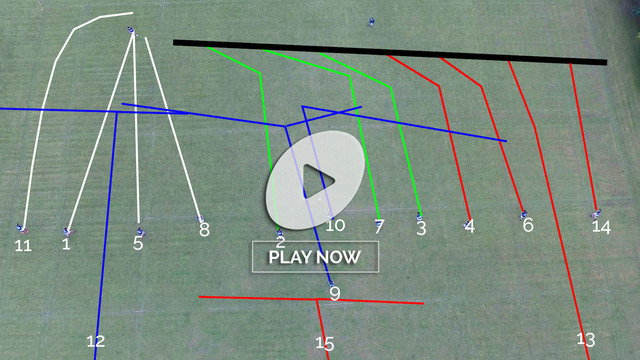

The positioning of the #9, #12 and blindside wing provide a lens through which to investigate the possibilities. At lineouts in the opposition ‘red zone’ [within the 22], Ireland often drop their scrum-half and blind-side wing in directly behind the drive, but away from the ball:

This is a ‘6+1’ formation with all the forwards involved in the drive. #7 Josh Van der Flier [‘1’ in the red hat] takes the ball from the receiver, then ‘2’ hooker Dan Sheehan works around behind him, in the second tier of the drive. All three of #9, #12 and the blindside wing have a broad choice of options, depending on how the play develops. In this case both #11 Lowe and #12 Bundee Aki join the drive before Ireland even reach the 5m line – the usual trigger for backs to participate in a maul.

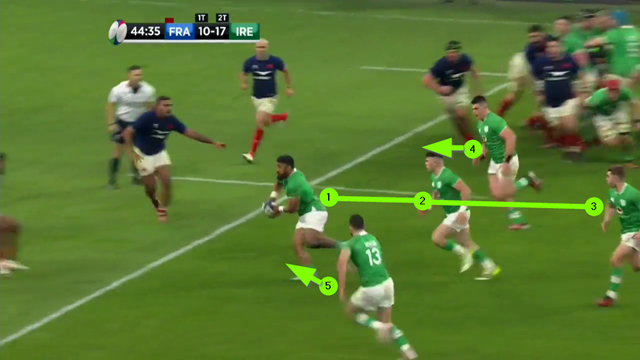

Ireland did not score on a try this visit to the French 22, but they used it as the setting for a try scored on the hour mark:

With only five forwards, not six in the line, and Lowe and Aki staying conspicuously away from the maul, the defending French forwards must have been thinking ‘pass’ rather than ‘drive’. When they overload on Tadhg Beirne [in the blue hat] on the infield corner, Ireland takes the ball straight through the middle to convert on the ultimate decoy play.

Towards the end of the game, Ireland revisited their original plan with greater success:

Lowe and Aki again join around seven metres out from the line, and they are not bit-part players, but key blockers taking the ball right through the heart of the French defence, all the way to the goal-line. The importance of replacement scrum-half #22 Conor Murray’s contribution is also noteworthy. With the head of the ball-carrier [replacement #2 Ronan Kelleher] buried in the drive, Murray is functioning as its ‘eyes and ears’ – seeing the space and acting as a rudder to Kelleher’s motor.

Ireland varied their use of the key personnel from driving lineouts further downfield:

In the first clip, Gibson-Park ushers his partner-in-crime, blindside wing [#14 Calvin Nash] over to join the ‘power I’ formation behind Aki and #10 Jack Crowley in midfield. In the second example, Nash is in the same ‘power I’ with Aki and Crowley, with options outside [Robbie Henshaw] and inside [Dan Sheehan] and Gibson-Park reserved for the second play.

Summary

The driving lineout is fast becoming the most creative source of offensive thinking in the professional game. You can add or subtract forwards to the line in a confident, 85-90% expectation of winning the ball. You can carry out the threat to maul or use it as a decoy to concentrate defending forwards in one area. You can vary the positioning of the three key backs – #9, #12 and the blindside wing – on first phase, adding them to the drive or shifting them across towards attacking formations in midfield. The only limit is the imagination of the attack coach.

.jpg)

.jpg)