Why the Lions series confounded expectation

The recent series between the New Zealand All Blacks and the British & Irish Lions was one which confounded expectation. Received wisdom suggested that the Lions needed to dominate set-piece and gain ascendancy over the Kiwi tight forwards in order to succeed.

In the event, the All Blacks enjoyed 58% of territory and 60% of possession, as well as emerging from the penalty count with a useful +5 advantage over the course of the series as a whole.

The Lions by contrast, were successful in departments of the game which are not supposed to be traditional areas of Northern Hemisphere strength – at least, not in the professional era. They manufactured most of their scoring opportunities off turnover or kick return or early phase lineout attack.

The outstanding try of the series derived from a counter-attack from a Kiwi kick ignited from deep within his own 22 by the Welsh full-back Liam Williams, while the Lions’ three other tries all came from lineout platforms.

As long ago as July 2016, I wrote the following article for Rugby World magazine:

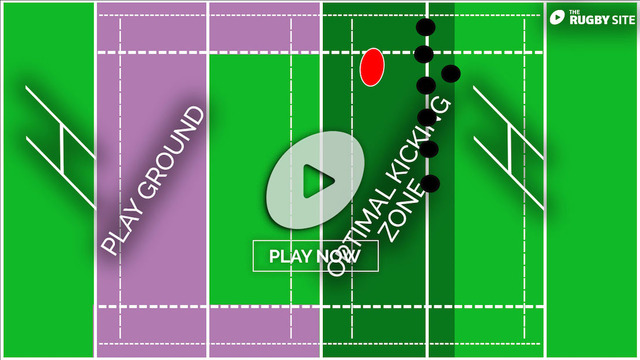

In it I explained the importance of committing the New Zealand backfield players (typically the full-back and two wings) as a preface to an attack utilising the full width of the field.

Wales had been quite successful at committing the All Black backfield defenders with high kicks before shifting the ball, and the Lions were able to take the same principle to a higher level with their superior kickers at 9, 10 and 12 (Conor Murray, Johnny Sexton and Owen Farrell).

I also projected that the Lions would need twin playmakers and a back three built for high ball contest and counter-attack in order to implement their counter-punching style:

The selection of the Lions backs next summer doesn’t look too difficult at all. Twin first receivers will probably be necessary in order to bolster the kicking game and enable those quick wide-wide transfers, and the Lions have two available in the shape of George Ford at 10 and Owen Farrell at 12. Wales’ Jonathan Davies can supply the power and straight-line threat at 13.

In the back three, a combination of Scotland’s Stuart Hogg at 15, with Liam Williams at 11 and either George North or Anthony Watson on the right wing, would give an excellent balance of speed, elusiveness and power.

George Ford wasn’t selected so Johnny Sexton filled that role, and Stuart Hogg was injured early on in the tour with Elliott Daly coming in on the left wing and Williams shifting to full-back.

But the theme of selection remained the same – to win shorter, contestable high kicks back, commit the All Blacks’ backfield defenders and shift the ball wide using two distributors with experience at #10 on the following phase(s).

It was the ability to counter-punch effectively in these situations that kept the Lions in the game in the vital third Test at Eden Park. Here are two examples from the first half:

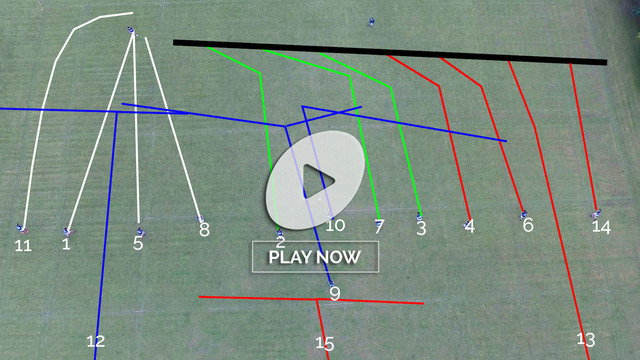

As soon as Elliott Daly makes the catch ahead of Israel Dagg, the All Blacks’ backfield is committed. Dagg is on the wrong side of the ball and #15 Jordie Barrett has to tackle Daly:

When Owen Farrell receives the ball at first receiver on the following phase, all three of the All Black backfield defenders are either in line (Savea) or on the wrong side of the field (Barrett & Dagg).

Unfortunately the left-handed pass from Murray floats too high for Farrell to take the obvious option of a cross-kick into the empty space beyond Lions’ right wing Anthony Watson, but the opportunity is there nonetheless.

In the second example, the Lions do manage to make the break after another high kick reclaim by Watson over Julian Savea:

Here the full force of the twin playmaker system makes itself felt, with Sexton and Farrell exploiting the opportunity to run at the forwards (Kieran Read and Sam Cane) opposite them.

The final frame from the sequence illustrates another reversal of expectation from the series. The All Blacks always tend to dominate the support channels after a break is made, whether they are on offence or on defence. In this instance, as Sexton plunges through the tackle of Cane, it is the two Lions’ support players who are closest to the ball, with Farrell in position to take the ground offload from Sexton:

It was this focus on consistent support play which enabled the Lions to bring off their first try of the series. There is always a support player in the ‘sweet spot’ directly behind the ball-carrier as he goes into contact:

Summary

One of the most unexpected developments of the recent series (well, not completely unexpected!) was the way in which the Lions had the courage to play in unstructured situations, and developed their skills in those scenarios.

Their selection in the back three for the first Test at Eden Park, with Liam Williams at full-back instead of Leigh Halfpenny, announced their intention, and they stuck to it throughout.

They got good purchase in the aerial battle from accurate high kicking and chasing from their wings, they were prepared to counter from deep, and they selected two playmakers at #10 and #12 in order to use the full width of the field and maximise the advantage they received from those situations.

Will the Northern Hemisphere continue to grow the green shoots evident in the Lions’ approach, or will it return to the older tradition of the set-piece and tactical kicking game?

I believe that the transformation is already well underway in competitions like the English Premiership and the Guinness Pro 12, so we can expect the growth of the game in the North to move it closer to the style already being played down South with reasonable confidence. But let’s not expect too much, too soon – for “to diminish expectation is to increase enjoyment”!

.jpg)

.jpg)