It all used to be so simple back in the day. You won the ball at the back of a lineout, then knocked it down to a big forward rumbling around the corner, usually with only a petrified number 10 standing in his way.

That is how the lineout peel used to work, and here is a typical example from the 1976 Grand Slam game between Wales and France:

The Wales number 8 Mervyn Davies taps the ball down for formidable tight-head prop Graham Price to take ball deep into the French midfield, breathing fire and snorting like a bull.

In the amateur days, forwards used to stay rigidly in place. The hooker stood in the tramlines in the 5-metre zone, watching his opposite number as he delivered the ball. The two second rows stood at #2 and #4 in the line, with the number 8 at the tail. The two sets of backs stayed dutifully in the back line.

It is all so different now. With the evolution of defence in the professional era, you are more likely to see the hooker defending around the end of the line rather than standing in the 5m corridor, which can often be tenanted by the scrum-half, the blind-side wing or even a number 10.

Lineout receivers on both sides move up and down the line, wherever they smell a weakness. There is far more positional versatility, and it has changed the character of the lineout peel. Nowadays it is just as likely to be directed around the front end of the line as it is the tail.

One of the primary attractions is that attacking teams will now be far more likely to find a small back defending that zone. There were three prominent instances of the front lineout peel, all with a slightly different flavour, from the final round of the group stages in the European Champions Cup.

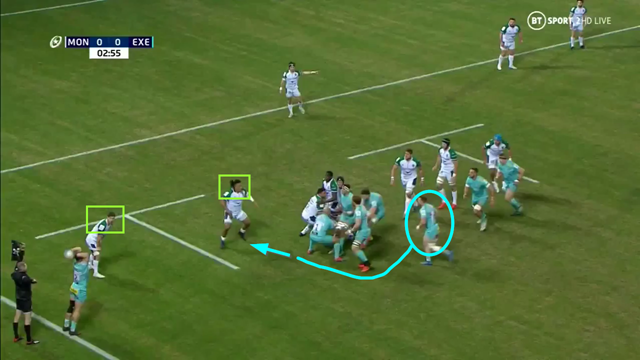

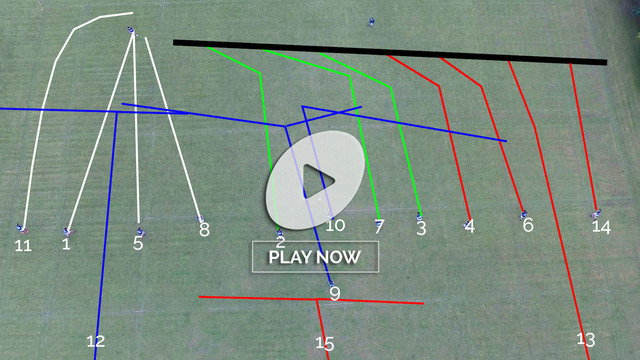

The first example comes from the match between Montpellier and Exeter in France:

The basic idea to introduce a dynamic ball-carrier into the 5-metre zone, who will overmatch the defender(s) in the area. In this case, Exeter’s powerful ball-carrying number 8 forward Sam Simmonds starts as the “+1” in the halfback slot, and then swings around to attack the two Montpellier defenders, number 2 Brandon Paenga-Amosa and number 11 Vincent Rattez:

Paenga-Amosa is too slow to get into a solid tackling position, and Rattez is not powerful enough to hold Simmonds in contact.

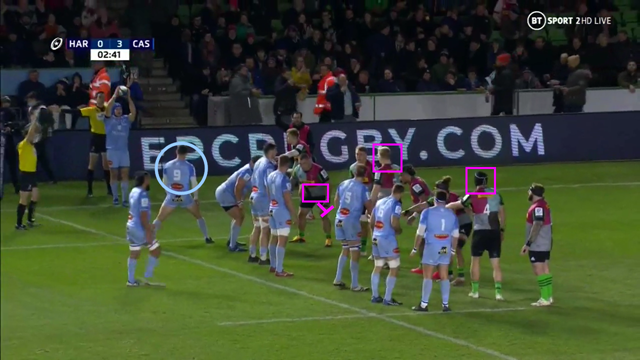

Two more tries were scored, by creating variations on a theme, in the game between English Premiership champions Harlequins and their French opponents, Castres:

From the touch-line view, the try looks fairly simple. The Montpellier scrum-half Rory Kockott moves up to the front of the line to exchange passes with hooker Gaetan Barlot, and Barlot beats both the Quins halfback and the blind-side wing to convert the opportunity.

The snapshot just before the throw reveals more about the choice of play:

The two Quins second rows are loading up at the back end of the line, and the front prop is already turning in to make a lift in the middle. If Kockott and Barlot can get the timing of their exchange of passes right, they are already set to overwhelm the Quins’ defender in the 5m channel.

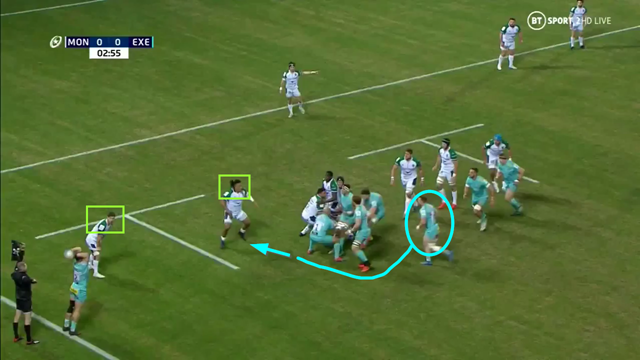

Not satisfied with one try around the front end of the lineout, Castres then brought off an even more ambitious move to score a second towards the end of the first period:

Instead of introducing their scrum-half at the front of the line, on this occasion Castres have inserted their blind-side wing (number 11 Filipo Nakosi) at the back:

Once again, the Harlequins’ forwards are grouped in the back half of the line, so the defence of the 5m corridor is relatively thin. Their resources in that area become even thinner when Barlot pulls away Quins’ number 8 Alex Dombrandt to the open-side with a decoy run.

Once the Quins’ halfback has been isolated, Nakosi is far too strong to be stopped by a mere arm tackle, and the situation resolves into a straightforward two-on-one versus the defensive blind-side wing.

Summary

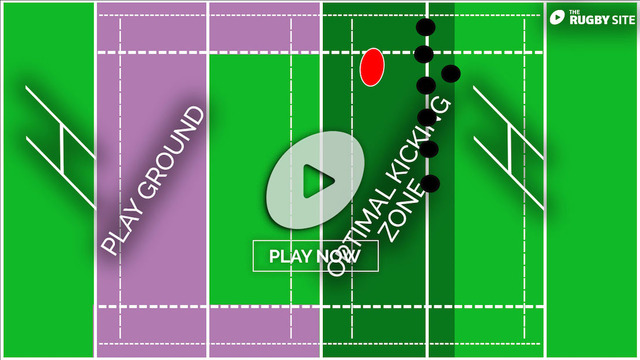

The times they are a-changing, and peels from the lineout are no longer confined to the open-side of the field. With so many players shifting position on both sides of the ball, backs and forwards alike, there is ample opportunity to deliver attacking options around the front end of the line, and match up a powerful ball-carrier with a weaker defender in the 5-metre corridor.

.jpg)

.jpg)