Winning “the race” & targeting weaknesses at lineout time

Jase Ryan’s excellent primer series on lineout execution focuses on the nuts and bolts of technique which can optimize your ability to win lineout ball quickly and easily. We can build on that foundation by observing how it works in a modern professional lineout at the elite end of the game, which combines accuracy at the throw & catch with smart calling to expose opposition weaknesses.

The 2017 summer series between the All Blacks and the British & Irish Lions featured two of the best lineout combinations in world rugby since South Africa’s Victor Matfield finished playing for the Springboks.

The New Zealand lineout captained by Kieran Read has been consistently the best international lineout since Matfield’s retirement, while the Lions’ lineout – coached by Steve Borthwick and called by George Kruis – fielded the best component parts the Northern Hemisphere had to offer.

The Lions would have been looking to make inroads into the New Zealand lineout throw in the first Test at Eden Park, and it didn’t take long for a prime opportunity to present itself.

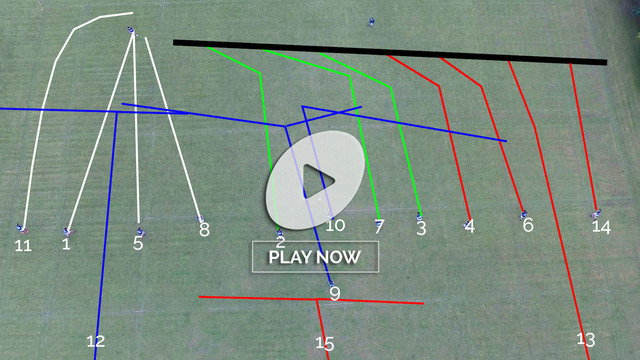

In only the third minute of the match, the Lions forced a pressure lineout position only five metres from the New Zealand line:

The Lions have positioned their two lineout aces (Ireland’s Peter O’Mahony and Kruis) opposite the two most likely All Blacks receivers, Read and Sam Whitelock behind him.

Their ‘weight’ is front-loaded on to O’Mahony, with the front lifter Tadhg Furlong already in a squat, ready to grip the knees in the vice Jase Ryan recommends. The back lifter Kruis is looking straight down the line, preparing to time his lift off the movements of the New Zealand hooker Codie Taylor.

The All Blacks’ task is to maintain their technical accuracy so close to their own goal-line while doing something to offset the Lions’ tight defensive formation.

Now let’s look at how they achieve their objective:

With the Lions committed to the pod on O’Mahony, Kieran Read calls the throw to the receiver behind him, Sam Whitelock. At the highest point of his jump, Whitelock and his support are in perfect position to win the ball, while the Lions have no way of competing:

Read is firmly locked on to Whitelock’s knees in the front lift, while Joe Moody is at full vertical extension and providing an stable ‘bucket’ for the receiver at the back. He is positioned almost directly beneath Whitelock and there is no space whatsoever for the Lions to penetrate in between the two lifters and the receiver as the pod shuffles slightly backwards to take the throw – as far away as possible from the Lions’ zone of competition.

The second New Zealand lineout in the 4th minute was a more direct example of ‘winning the race’ to the ball in the air:

In this instance, the two Lions’ poachers (O’Mahony and Kruis) are looking straight across the line at their opposite numbers:

This means that they will be relying on tell-tale movement from the Kiwi receivers to time the jump. They cannot observe the New Zealand thrower at the same time, so the All Blacks call a ‘throw-trigger’ in response. The ball is thrown first, then Kieran Read goes up and gets it. With Read’s speed and explosiveness into the air, the Lions are always going to be second best from their initial set-up:

Look at the line of the shoulders – Read is up first and Kruis cannot hope to match his speed and elevation.

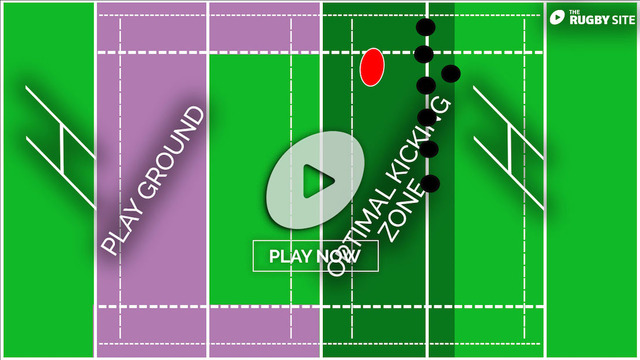

The first two Lions’ lineouts of the game provided examples of excellent calling strategy, and the use of different formations to offset the defence:

With six forwards in the line and a seventh (Sean O’Brien) at half-back, the Lions have chosen to split the line into two clear halves of three players each. This has had a definite impact on New Zealand’s ability to compete. While they have Sam Whitelock ‘in pod’ and ready to compete at the back, at the front Jerome Kaino has been left to oppose O’Mahony, and this represents a mismatch.

The result is that the Lions win easy unopposed ball, with the All Blacks staying on the ground:

The final example demonstrates how a lineout formation can be altered before the throw in order to dilute the competition:

The All Blacks are primed to compete at the front at the start of the lineout, with Brodie Retallick supported by Moody in the ‘front squat’ position and Whitelock prepared to provide the ‘bucket seat’ behind him.

George Kruis’ response is to spread the lineout out towards the edge of the 15 metre line, which dilutes the pod on Retallick and allows the Lions’ half-back (Taulupe Faletau) to enter the play:

With Faletau swinging around to become the back lifter and Kruis switching from front to tail, Peter O’Mahony is able to take the ball over another aerial non-combatant in the shape of Joe Moody!

Summary There are two basic methods of countering a team with a strong defensive lineout. You can choose to beat them with the accuracy of your technical processes and the speed and explosiveness of your receiver into the air; or you can adjust your formation to take their most dangerous aerial competitors out of the game.

Jase Ryan’s series on lineout execution provides a lucid foundation for improving techniques on the lift and receipt, and shows how to manoeuvre a pod effectively while it is airborne.

Beyond that, it becomes a matter of strategy and switched-on calling by your lineout captain. He/ She must be able to read opposition formations and devise realistic ways of throwing away from the strongpoints in it. If you can satisfy both requirements, you are on the road to a 90%+ success rate, whatever the pressure!

.jpg)

.jpg)