They may as well call scrum-halves like Aaron Smith and Antoine Dupont ‘The Running Man’. The GPS ratings of the modern number 9 are typically off the scale. As ball-in-play time rises steadily towards a range between 35 and 40 minutes per game, the starting halfback can reasonably be expected to run about 8 kilometres before his inevitable replacement around the hour mark.

To give that figure some context:

a top front-rower would be expected to cover approximately half the distance. A ball-control team would be looking to set over 100 rucks during a match, and the scrum-half would be expected to attend about 95% of those breakdowns.

A professional number 9 will be running, jogging or sprinting about 20% more than any other player on the field, so the demands are sky high.

The modern scrum-half not only has to be the fittest man on the paddock in terms of aerobic endurance, he also has to be able to use his judgment. He cannot simply run from point to point blindly, he needs to calculate the probabilities of where on the field a play will be most likely to resolve itself and take the shortest path to the ball.

Increasingly, the number 9 also has to be one of the most flexible players in the back-line, in terms of the number of roles he is expected to fulfil. Nowhere is the positioning of the scrum-half more critical than during the kicking duels that develop, with the ball pinging from one end of the field to the other.

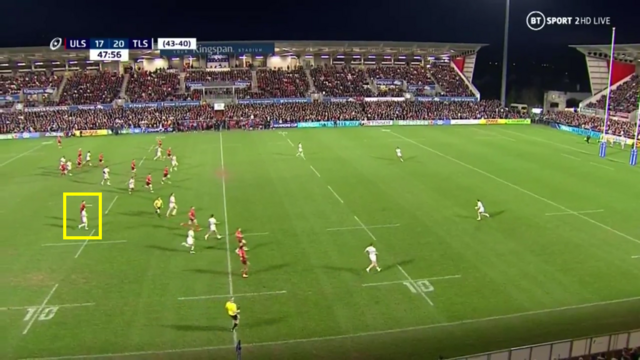

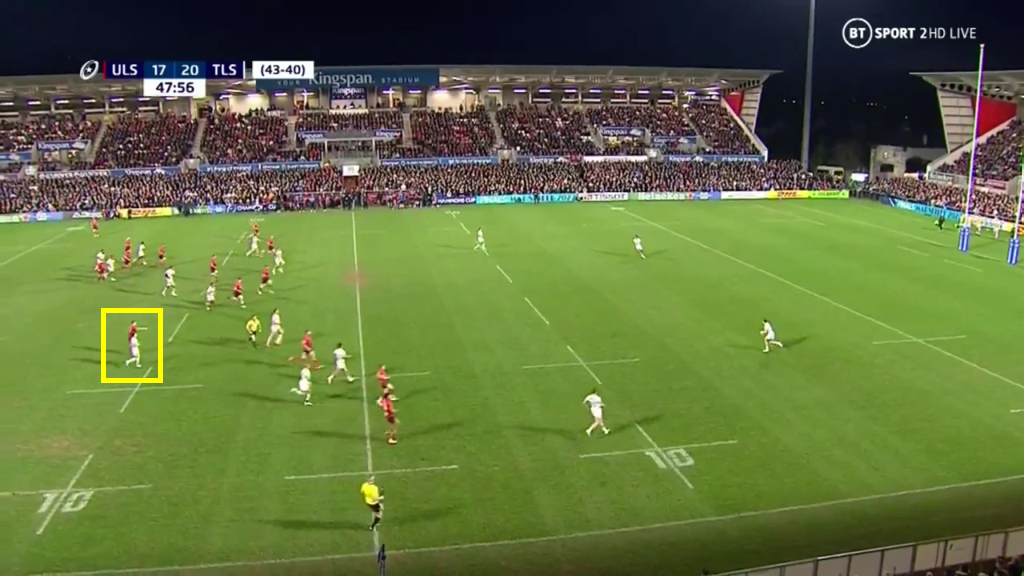

In the recent Heineken Champions Cup knockout game between Ulster and Toulouse, the French half-back [and World Player of the Year] Antoine Dupont was often left as the furthest defender upfield in the course of those kicking duels:

In this instance, Dupont is the furthest back upfield as Ulster prepare to return a kick from the right half of their backfield zone. He not only makes a decisive frontal tackle on Ulster full-back Michael Lowry, he is back on his feet to lead a counter-ruck and chase through on to his opposite number.

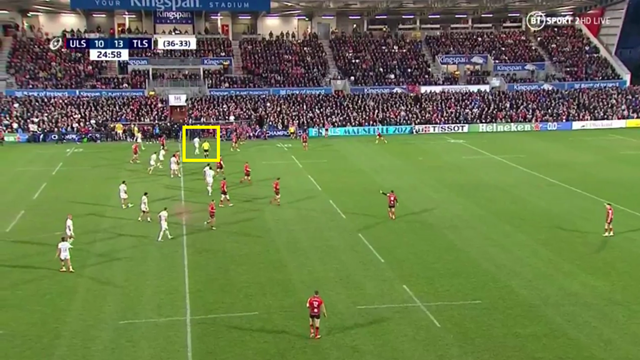

The multi-functional nature of the modern scrum-half’s role was reinforced at a similar sequence later in the game:

Once again, Dupont is left upfield as Toulouse prepare to return a kick. He has to accurately predict the location of the first ruck and his optimal role at the tackle: in this case, he makes an excellent decision to become the first cleanout player over the top of Toulouse full-back Thomas Ramos near the Ulster 40m line, rather than the passer from the base. The ball is won quickly and attacking tempo is maintained.

The best two scrum-halves in world rugby are probably Dupont and Aaron Smith. Here is one example of ‘Nugget’s’ interpretation of the same role in the kick return:

Like Dupont, Smith starts the play as one of the two highest defenders, and quickly picks up a short-cut straight across field which will take him to the first ruck directly. A couple of plays later, he is back doing what he does best: creatively making play with a delicate top-spun chip over the top of the Hurricanes defence on the short-side.

Both Smith and Dupont are eminently capable of playing out of the backfield, when needs must. When he is playing for his country rather than his club, Antoine Dupont often drops into the two-man zone in the backfield, in order to become an initiator of counter-attacks. The following instance comes from the Six Nations match between Les Bleus and Scotland:

Although Nugget may lack Dupont’s power and threat on the break, he remains a terrific tactical visionary on the counter from the back:

Aaron Smith is already signalling policy on the next play to Highlanders’ number 10 Marty Banks before the ball is ever won back from the kick; he is there to pick up the pieces and zip a pass out to the right side-line, before providing width to the left from the base of the next ruck. As if that was not enough, he takes the short-cut straight across the park to ensure he is there to service the breakdown formed over the top of James Lentjes on the opposite side of the field.

Against Ulster, Antoine Dupont finished his day by moving to first five-eighth for the final 10 minutes of the match, and scoring the winning try from that spot!

Summary

The positional demands are nowhere higher on a rugby field than they are for a modern number 9. He has to run further than anyone else and attend at the base of an ever-increasing number of rucks. He has to predict where those breakdowns will be when the ball balloons back and forth over his head during (often interminable) kicking duels, and play a variety of roles when he arrives. He has to defend in the front line, or initiate counters from the backfield while always taking the shortest path to the ball. And at the end of it all, he needs enough breath left to talk back to the referee and debate every single decision at length! It is some feat of arms.