The maul remains one of the most contentious issues in rugby. The further up the ladder of the professional game that you progress, the more contentious it gets. Typically starting from a lineout set-piece starter, it is one of the few areas of Rugby Union where obstruction ahead of the ball is legal.

In fact, both teams will try to play as far ahead of the ball as possible at the maul. In this article posted over two years ago https://www.therugbysite.com/blog/set-piece/how-to-cheat-effectively-in-maul-defence, I outlined how defenders will try to exploit the loose binding rules at the edge of the drive to sneak around the side and all the way on to ball-carrier to prevent release.

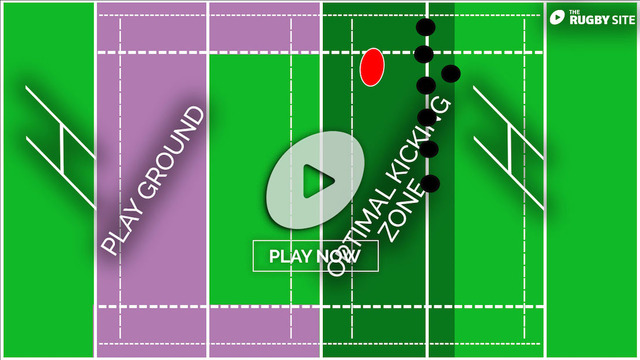

Since then, that ‘easy cheat’ has been employed at every level of the professional game to disrupt the drive from lineout. The onus has tended to fall on the attacking side to come up with new innovations. I examined one of the solutions, sponsored by South Africa, in this article https://www.therugbysite.com/blog/set-piece/how-to-create-breathing-space-for-the-lineout-drive. The receiver is held in the air for as long as possible to force mis-timings and discourage an aggressive early drive by the defence.

One of the great iconic driving teams in world rugby, the Brumbies from the Australian Capital Territory, have come up with another answer in Super Rugby Pacific 2022.

First of all, a quick reminder of some of World Rugby’s key rules at the maul:

The ball-carrier in a maul may go to ground provided that player makes the ball available immediately. Sanction: Scrum.

All other players in a maul must endeavour to stay on their feet.

All players in a maul must be caught in or bound to it and not just alongside it.

Players must not:

a. Intentionally collapse a maul or jump on top of it.

b. Attempt to drag an opponent out of a maul.

The laws are sufficiently amorphous to encourage any number of changes of bind or direction by the attacking side, so they have a long rope to play with. The Brumbies have focused on using one of the main two blockers who comprise the front wall to steer defensive players away from the true direction of the drive.

Their key man against the Hurricanes in the recent SRP quarter-final was the rear lifter, second row Darcy Swain. Swain is a big man at over 6 foot 7 inches tall, so he can get the receiver (Caderyn Neville) up to dizzy heights in order to win the ball in the first place:

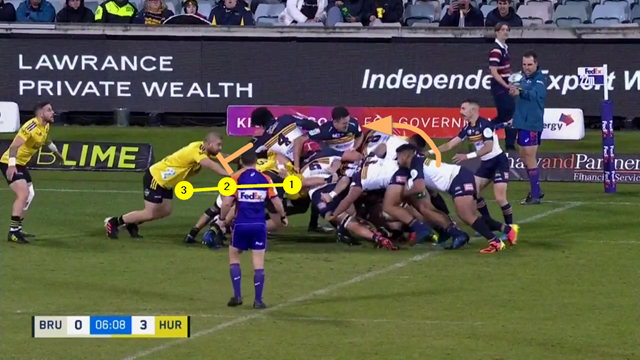

This 6th minute lineout set the tone for what would happen later in the match. After supporting the take by Neville, Swain’s first task is work ahead of the receiver and become the spearhead of the drive on the outside or infield corner:

The Brumbies’ second row is already well ahead of Neville, and crucially he has managed to turn his body so that he is now front on to the defence. From this position he can achieve further penetration and begin to pick off defensive bodies (Hurricanes “1”, “2” and ”3”) on his side of the drive.

As the clip illustrates, Swain is looking to use a typical defensive technique to swim through the middle of the maul and split it into two parts. The ultimate aim will be to shear off those three defenders on the Brumbies left side and then move the drive in the opposite direction. That is what happened in the next close-range example:

By 24:43 on the game-clock, Swain has already turned North-South to face the opposition goal-line, and engaged the back man in the maul defence, Hurricanes’ hooker Dane Coles.

From his advanced position, Swain can separate those three defenders from the maul all by himself, and the dam breaks on the opposite side, leading to the Brumbies’ first try of the game. Did he drag them out of the maul intentionally? It is not a call many referees would be prepared to make.

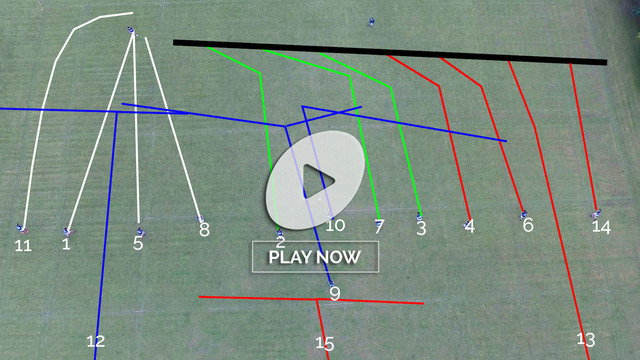

Swain’s activity on that infield corner was also key to the final try of the match, which put the result beyond all doubt. Let’s break the score down into three phases:

In the first phase, Swain has advanced beyond the catcher (Nick Frost), faced front and begun to engage the three Hurricanes defenders on his side of the maul after a change of bind.

In the second phase, Swain has peeled no less than four defenders away on his own, and a couple of extra Brumbies backs have been added to the drive over the other side.

In the third phase, the short-side defence has been permanently depleted, and the two Brumbies backs who joined the drive (#12 Irae Simone and #14 Tom Wright) have recycled themselves to that wing, with Wright dotting the ball down for the try:

Summary

There is still plenty of wriggle room under the laws governing the maul, for both teams. Defensive teams have become expert at creeping around the sides and on to the ball-carrier at the back, offensive teams have held up the receiver to force mis-timings and a more passive attitude by the D.

Now maul experts like the Brumbies are using one of their lifters to penetrate the defensive screen and split it away completely from the intended direction of the drive. It frees the maul and opens up the short-side to attack on subsequent phases. The ball is in the defence’s court!

.jpg)

.jpg)